![]()

Figure 1.1

1

The war on compassion

In our lifetime, what was not supposed to happen “ever again”—genocide—has instead happened again and again. As Samantha Power shows in A Problem from Hell (2002), her study of genocide in the twentieth century, the perception of genocide is all in the framing. Governments acting against a minority want the violence to be perceived as civil war or tribal strife, as quelling unrest and restoring order, as a private matter that does not spill over into the international community. Other governments weigh their own national interests against the needs of those being killed.

After watching the movie Hotel Rwanda and as I began reading A Problem from Hell, among the many disturbing questions that surfaced for me, besides the obvious one—How could we have let this happen?—was the question, How can we get people to care about animals when they do not even care when people are being killed?

But as this question came to mind, I realized that it was the wrong one because it accepts a hierarchy of caring that assumes that people first have to care about other people before they care about animals and that these caring acts are hostile to each other. In fact, violence against people and that against animals is interdependent. Caring about both is required.

While I could not read about genocide without thinking about the other animals and what humans do to them, I am sophisticated enough to know that this thought is experienced as an offense to the victims of genocide. However, I am motivated enough to want to ask more about the associations I was thinking about and sensing because human and animal are definitions that exist in tandem, each drawing its power from the other in a drama of circumscribing: the animal defining the human, the human defining the animal. As long as the definitions exist through negation (human is this, animal is not this, human is not that, animal is that—although what is defined as human or animal changes), the inscription of human on something, or the movement to be seen as human (for example, Feminism is the radical notion that women are human), assumes that there is something fixed about humanness that “humans” possess and, importantly, that animals do not possess. Without animals showing us otherwise, how do we know ourselves to be human?

Despite all the efforts to demarcate the human, the word animal encompasses human beings. We are human animals; they, those we view as not-us, are nonhuman animals.

Discrimination based on color of skin that occurs against those above the human–animal boundary is called racism; when it becomes unspeakably murderous, it is called genocide. Discrimination by humans that occurs against those below the human–animal boundary is called speciesism; when it becomes murderous, it is called meat eating and hunting, among other things. The latter is normalized violence. Is it possible that speciesism subsumes racism and genocide in the same way that the word animal includes humans? Is there not much to learn from the way normalized violence disowns compassion?

When the first response to animal advocacy is, How can we care about animals when humans are suffering? we encounter an argument that is self-enclosing: it re-erects the species barrier and places a boundary on compassion while enforcing a conservative economy of compassion; it splits caring at the human–animal border, presuming that there is not enough to go around. Ironically, it plays into the construction of the world that enables genocide by perpetuating the idea that what happens to human animals is unrelated to what happens to nonhuman animals. It also fosters a fallacy: that caring actually works this way.

Many of the arguments that separate caring into deserving/undeserving or now/later or first those like us/then those unlike us constitute a politics of the dismissive. Being dismissive is inattention with an alibi. It asserts that “this does not require my attention” or “this offends my sensibility” (that is, “We are so different from animals, how can you introduce them into the discussion?”). Genocide, itself, benefits from the politics of the dismissive.

The difficulty that we face when trying to awaken our culture to care about the suffering of a group that is not acknowledged as having a suffering that matters is the same one that a meditation such as this faces: How do we make those whose suffering does not matter, matter?

False mass terms

All of us are fated to die. We share this fate with animals, but the finitude of domesticated animals is determined by us, by human beings. We know when they will die because we demand it. Their fate, to be eaten when dead, is the filter by which we experience their becoming “terminal animals.”

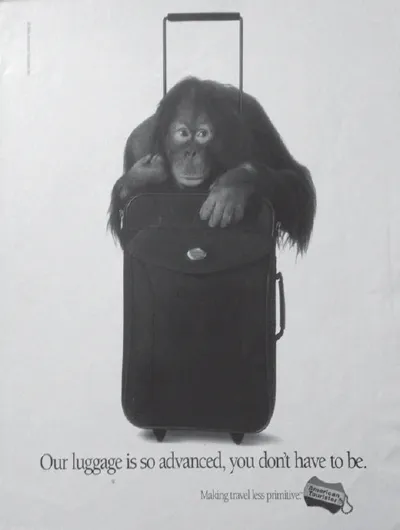

The most efficient way to ensure that humans do not care about the lives of animals is to transform nonhuman subjects into nonhuman objects. This is what I have called the structure of the absent referent (Adams 2015: 21). Behind every meal of meat is an absence: the death of the nonhuman animal whose place the meat takes. The absent referent is that which separates the meat eater from the other animal and that animal from the end product. Humans do not regard meat eating as contact with another animal because it has been renamed as contact with food. Who is suffering? No one.

In our culture, meat functions as a mass term (Quine 1960: 99; Adams 1994b: 27), defining entire species of nonhumans. Mass terms refer to things like water or colors; no matter how much of it there is or what type of container it is in, water is still water. A bucket of water can be added to a pool of water without changing it. Objects referred to by mass terms have no individuality, no uniqueness, no specificity, and no particularity. When humans turn a nonhuman into “meat,” someone who has a very particular, situated life, a unique being is converted into something that has no individuality, no uniqueness, and no specificity. When five pounds of meatballs are added to a plate of meatballs, it is more of the same thing; nothing is changed. But taking a living cow, then killing and butchering that cow, and finally grinding up her flesh does not add a mass term to a mass term and result in more of the same. It destroys an individual.

What is on the plate in front of us is not devoid of specificity. It is the dead flesh of what was once a living, feeling being. The crucial point here is that humans transform a unique being, and therefore not the appropriate referent of a mass term, into something that is the appropriate referent of a mass term.

False mass terms function as shorthand. They are not like us. Our compassion need not go there—to their situation, their experience—or, if it does, it may be diluted. Their “massification” allows our release from empathy. We cannot imagine ourselves in a situation where our “I-ness” counts for nothing. We cannot imagine the “not-I” of life as a mas...