![]()

1

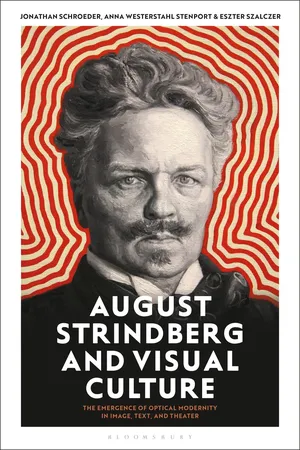

Introduction: Visual Culture, August Strindberg and the Double Image of Modernity

Eszter Szalczer, University at Albany, SUNY, USA, Anna Westerstahl Stenport, Georgia Institute of Technology, USA and Jonathan Schroeder, Rochester Institute of Technology, USA

In his essay ‘A Glance into Space’ (Un Regard vers le Ciel’), first published in the French occultist magazine l’Hyperchimie in 1896, August Strindberg writes

[i]s the sun round because it looks round to us? And what is light? Something outside me or within, subjective perceptions? … Is it … the inside of the eye that the astronomer reproduces in word and image, and is it the lenses of the telescope that he photographs on the photosensitive plate? (2006a: 165–166).

These reflections exemplify the centrality of vision in August Strindberg’s creative process. The exploration of the visual represents the common thread that links all of Strindberg’s multifaceted oeuvre together, from drama and fiction through scientific and occultist studies to painting and photography. This book places the rich and heterogeneous oeuvre of this extraordinarily prolific artist within the framework of visual culture in an attempt to understand connections between modernity and visuality and the perceptual and representational paradigm shifts constituted through these connections.

August Strindberg and Visual Culture brings together scholars, practitioners, artists and public intellectuals in novel constellations to reassess a major literary figure from the perspective of visual theory and art history. In keeping with Strindberg’s boundary-crossing, experimental and multi-modal strategies of making art, the book engages interdisciplinary approaches that inform the study of the works, practices and larger cultural context of his work.

Together, the chapters elaborate, for the first time, how August Strindberg’s writing and artistic practice presage and influence key visual theories of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. August Strindberg and Visual Culture provides a new and ground-breaking perspective on a complex and prolific body of work by exploring how his radical conceptions of the visual led him to challenge the boundaries of such traditionally conceived literary and visual arts genres as drama, fiction, non-fiction, photography and painting. Beyond his own visual production, however, the book explores his continuing influence on visual culture, by looking at contemporary connections to his work within photography, stagecraft and visual art.

The book charts vital intersections between theatre, aesthetic theory and visual elements in Strindberg’s work that have been left largely unexplored. Thus, rather than following traditional genre-bound critical approaches, the contributors navigate through uncharted – and in Strindberg’s case – extremely productive territory by focusing on the intermediality of individual works, the corpus as a whole, and their connections to a wide array of historical and contemporary artists, writers, photographers, film, theatre and museum practitioners. Our broader aim is to establish a new conceptual framework for integrating visual culture and cinema studies with theatre practice and modernist drama.

Visual culture can be described as a field of study ‘concerned with visual events in which information, meaning, or pleasure is sought […] in an interface with visual technology’, the latter defined as ‘any form of apparatus designed either to be looked at or to enhance natural vision, from oil painting to television and the Internet’ (Mirzoeff 1998: 3). It is precisely its ubiquitous and dynamic relationship to visual culture that makes Strindberg’s contribution representative of the modern: the work of an artist confronted with a world that cannot be understood via traditional explanations; a world whose boundaries are constantly redrawn by a steady flow of visual information and visual technologies that seem to challenge received notions of inside and outside, subject and object.

‘Where does the self begin and where does it end?’ Strindberg asks himself as he continues speculating on the shape of the sun in ‘A Glance into Space’; ‘[h]as the eye adapted itself to the sun? Or does the eye create the phenomenon called the sun?’ (Strindberg 2006a: 166). These are not rhetorical questions for Strindberg but ideas that serve as launch pads for experimentation, using himself – whatever that means to him at that moment – as the object and the instrument, inserting his body into visual technology, making his eye serve as both lens and photosensitive plate, in an attempt to penetrate the surface of the visible and push deeper into the invisible.

What can be visible is an overarching concern for Strindberg. On the title page of his Occult Diary (1896–1907), he includes his favourite line from the Talmud as a motto: ‘If you wish to know the invisible, observe with an open gaze the Visible’ (Strindberg 1977: 3), indicating a constant awareness and practice of double vision. Even when interpreting his own paintings, in which he attempted to imitate what he construed as nature’s spontaneous way of creating images by chance, he saw both an exoteric and an esoteric meaning materialize in them simultaneously (Hedström 2001: 48–55). While working in varied genres and media, including fiction, poetry, theatre, non-fiction, illumination, sketching, painting, photography, linguistics and chemistry, among others, a pivotal impetus for Strindberg was what has been identified as the stated purpose of visual-culture research, namely, to problematize the visible, ‘to interrogate dominant readings, to trouble singular meaning’ (Campbell and Schroeder 2011: 1506).

W. J. T. Mitchell offers another influential definition of visual culture as ‘ “the study of the social construction of visual experience”, which represents a “pictorial turn” that permeates a whole variety of fields and disciplines’ (Mitchell 1995: 540–541). This ‘pictorial turn’ has been described as ‘the fascination with the visual and its effects that marked modernism’, which indicates ‘a growing tendency to visualize things that are not themselves visual’ with the help of increasingly advanced visual technologies that have the ‘capacity to make visible things that our eyes could not see unaided’ (Mirzoeff 1998: 3, 5).

What could be more telling of this fascination than the figure of the scientist Captain in Strindberg’s 1887 naturalistic play, The Father (Fadren)? The Captain boasts that with the help of a spectroscope – not a microscope, as his wife Laura would have it – he has ‘been analyzing meteorite samples and found carbon – evidence of organic life’, which means he is able to discern the past, ‘not what’s happening, but what has happened’ on the planet Jupiter (Strindberg 1981: 30). What is at stake here is the question of visibility: the irony that the Captain might be able to peer into his spectroscope and see evidence of life on other planets, but the view of his own progeny is rapidly being obscured as the certainty of his – and indeed of all fathers’ – paternity is brought into question.

Today, of course, DNA testing, a form of visual technology unavailable during Strindberg’s lifetime, would resolve the matter, but modernity’s questioning of origins remains, ever since the dawn of ‘the age of mechanical reproduction’ (Benjamin [1936] 1968). Strindberg continually embraced new visual technologies, including the X-ray, and incorporated photography and many other scientific, painterly, theatrical and cinematic techniques in his work. In part, Strindberg sought to unearth what he considered those lost origins – of language, of matter, of the world which, as the Poet says in A Dream Play (Ett Drömspel) (1901) is just ‘a false copy’ of the original – and to observe, capture, project, reproduce, mobilize and bring into dynamic relationships images, both textually and visually.

And thus, whereas Strindberg is known primarily as a playwright whose name hallmarks modern drama and theatre, the intent of this volume is to bring into focus a wider spectrum of his boundary-crossing work that included – beyond, or rather along with, literary representations – painting, photography, scenography, chemistry, botany, alchemy, performance practice, as well as philosophical, theoretical and historical reflections on innumerable aspects of these diverse fields. Approaching Strindberg’s work through the lens of visual culture helps us deconstruct artificial boundaries between the literary and the visual, between text and image, and between writer and artist. This approach, which is reflected in the individual chapters as well as in the structure of our book as a whole, seeks to respond to Strindberg’s own transdisciplinary practices and aesthetics. It also helps us to contemplate the fruitful simultaneity of artistic, scientific and mystical-occult modus operandi that Strindberg typically engaged in.

Strindberg and visual media

Strindberg’s work as a visual artist is usually divided into discrete phases of intense engagement followed by long periods of inactivity as painter or photographer. For example, after some early paintings in the 1870s, he would not return to the medium until 1892, the time of his divorce from his first wife Siri von Essen, while he was staying alone on the island of Dalarö in the Stockholm Archipelago. A new burst of paintings ensued during courtship and marriage with his second wife Frida Uhl in 1894 while living in Dornach, Austria, and then again during their soon-to-be separation and his departure for Paris, for a stay that extended into 1896. He then would not take up painting again until the early 1900s, commencing his final period as a pictorial artist (Söderström 1972; Hedström 2001: 9–101).

Similarly, although Strindberg had been interested in photography since his youth and had already owned a camera by 1861/62 (Hemmingsson 1963: 16), his first significant photographic enterprises, which included an unsuccessful attempt at the photographic documentation of an ethnographic journey through France for the book that eventually became Among French Peasants (Bland franska bönder) (1889), and a series of ‘impressionist’ family photographs taken in Gersau, Switzerland, occurred in 1886, after which he would return to the medium in the 1890s when his work included, besides family and self-portraiture, some remarkable experiments by manipulating photosensitive plates without lens and camera. Over a final period in the early 1900s Strindberg experimented with photographic ‘soul portraits’ and cloud studies using his so-called wonder-camera (the Wunderkamera), which he designed and constructed with fellow photographer Herman Anderson (see Hemmingsson 1963; Rugg 1997: 80–131; Szalczer 2001).

Strindberg’s theories, criticism, and practice of the visual arts, and his profound engagement with visual technologies were not simply a response to the currents of the times, with which he was intimately familiar. Rather, his own work with visual media often initiates a ‘radical and bold break with the image making conventions [bildkonventioner] of the later nineteenth century’ (Lalander 1999: 91, trans. by authors). That is especially the case with Strindberg’s approach to self-portraiture, and the ways in which he describes himself in visual terms in his autobiography, which challenges any notion of a unified self and explores an ambiguous relationship between the perspectives of ‘photographer and photographed, and photographing subject and photographed object’ (Rugg 1997: 102). For example, in his major study of Strindberg’s ‘visual imagination’, Harry G. Carlson presents Strindberg’s preoccupation with visual media during his years of exile in Berlin and Paris in the 1890s as a self-healing process, where ‘the coalescence of various forces in the fin-de-siècle climate of artistic renewal’ not only influenced his ‘personal renewal’ but also ‘enabled him to restart his creative engine and begin anew’ (Carlson 1996: 3).

According to the classic biographical approach of Strindberg studies (greatly informed by the author’s fictionalized autobiographies and numerous letters), his formidable contributions to visual culture have consistently been interpreted as the direct outcome of personal experiences and idiosyncrasies. It is true that some of Strindberg’s own production of visual media, especially his painting, tended to occur in moments of severe crises or periods of intense expectations – such as marital stress, psychotic episodes, or the impending birth of a child – often associated with simultaneously occurring writer’s block (Söderström 1991: 14). Biographical approaches have shed light on significant aspects of Strindberg’s work in the context of visual culture, though these interpretations unnecessarily confine Strindberg’s work to biographical matters.

August Strindberg and Visual Culture, on the other hand, foregrounds contributions to aesthetic and intellectual history and visual culture while minimizing the chronological and biographical in favour of the thematic, multi-modal and transdisciplinary. The book offers insights into Strindberg as a multimedia artist, whose writing is inseparable from his visual imagination and from the visual technologies of his time. Some scholars have indeed explored Strindberg’s interest in turn-of-the-century media technologies, including the laterna magica, the sciopticon and the panorama, from the perspective of media archaeology and media history (see, notably, Hockenjos 2007), informing many strands of this book. It is our contention that Strindberg epitomizes the modern writer precisely because his work is so deeply embedded in visual culture in meaningful and often anticipatory ways – as part of a ceaselessly ongoing and lifelong process. We do not believe that Strindberg’s visual practices are by-products of his life or offshoots of his writing (or of any difficulties in writing, for that matter). Instead, we examine what questions he was drawn to and led him to explore visual media and produce a heterogeneous and multi-variegated body of work.

Another aspect of Strindberg’s involvement with visual media is important to stress: a pronounced effort to fully explore the potentialities afforded by the specific medium at hand, especially in painting or photography. In other words, while image and text often appear combined, it seems that neither is there to merely serve or illustrate the other. Strindberg’s paintings, for example, completely disengage from literary (narrative) representation and often from an attempt at referentiality. Instead, they bear marks of attention to the material technologies pertaining to the medium and attempts to achieve as much ontological immediacy as possible. That includes the remarkable materiality of Strindberg’s paintings: he used a palette knife instead of a paintbrush and applied oil paint directly on wood or cardboard panel. This practice, moreover, has been described as displaying as powerful a presence of matter as the paintings of Anselm Kiefer, by which ‘the tactile surface not only presents a picture of nature, but also gives the impression of being a piece of nature’ (Feuk 1991: 11).

Double pictures and metapictures

‘Looking at images across disciplines can help us to think about the interrelatedness of different kinds of visual media’, observe Marita Sturken and Lisa Cartwright in their introduction to visual-culture studies (Sturken and Cartwright 2009: 2). This is precisely what this book undertakes. It explores the significance of intervisuality, that is, ‘the simultaneous display and interaction of a variety of modes of visuality’ (Mirzoeff 2002: 3) in Strindberg’s work and legacy.

As an introduction to this approach across Strindberg’s body of work, let us look at a few examples taken from different media he consistently explored and experimented with throughout his creative life: painting, drama and photography. The well-known 1892 oil painting Dubbelbild (Double Image), so dubbed by Göran Söderström (Lalander 1992: 26), in which one motif visible along two edges of the picture plane encloses another as if in an odd frame, provides a compelling case study of Strindberg’s playful exploration of the philosophies and practices of the visual (Plate 1.1).

The p...