![]()

1

Girls and Other Incomplete Things: On Archaeological Method

Archaeology at the end of the world

Towards the end of an essay on non-knowledge, ‘The Last Chapter in the History of the World’, Giorgio Agamben offers an image of what this zone would look like were we able to see inside of it. It is not a view as such, but a partial and momentary sighting, ‘one would only glimpse … an old and abandoned sled, only glimpse – though this is not clear – the petulant hinting of a little girl inviting us to play’.1 This slight yet suggestive image, however, furnishes the method of archaeology with a key component. The idea that a zone of non-knowledge or potentiality is off to one side, tangential to the world in which we live and yet pressing in and shaping its contours, underpins the practice of a philosophical archaeology. That there is an invisible cast around what we inhabit as the known world is a concept variously elaborated across Agamben’s work as potentiality, decreation, inoperativity and in-fans, from the earlier writings to the most recent. Yet the most potent figure that Agamben finds for non-knowledge is that of a small girl, a figure that operates recursively through both philosophy and film.

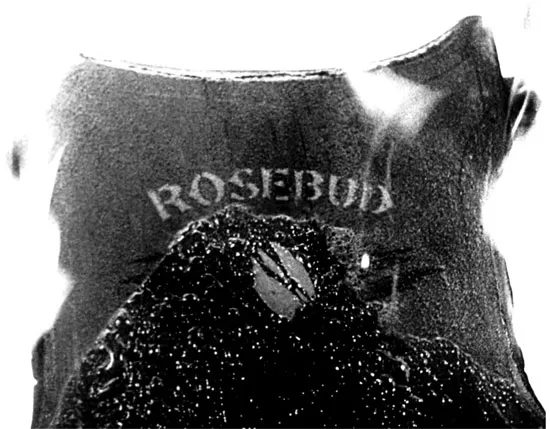

This petulant girl with the sled in the last chapter in the history of the world elides two images from the film Citizen Kane (Welles, 1941). The first is the famous sled that belongs to the boy at the beginning of the film and that is abandoned to the fire at the end, and the second is an image we never see but only hear about: a girl on a ferry sighted momentarily by Kane’s business manager. As she passes by on a departing ferry, he recalls ‘A white dress she had on. She was carrying a white parasol. I only saw her for one second,’ yet ‘[s]he didn’t see me at all’.2 Carried in another direction to a different future, the young woman nonetheless remains a force in his life. The half-formed, liminal girl borders on worlds but exercises distance and difference. She reappears as Dulcinea in Orson Welles’s unfinished film, Don Quixote, who seems to know more than everyone around her. Wherever she is from, we do know the girl’s language is that of gesture, not speech, and despite her peevishness she wishes to play, that activity which from Benjamin through to Agamben marks the suspension of the values of use and exchange. In this zone of non-knowledge, the laws of use and causality are arrested and the idea of completion is abandoned, for what proceeds here is a science of the potential and the partial.

Citizen Kane (1941)

This chapter practises and examines an archaeological approach to cinema through the prism of Agamben’s thought. Unlike geological archaeology that seeks to reconstruct a version of the past from a fragment, philosophical archaeology works from small clues or signatures hidden in the open and from across history to make a phenomenon intelligible for the first time. These details are scattered across the past and we may at first only glimpse them as they appear in radically different contexts. The task of the archaeologist is to put these signatures into correspondence and, in doing so, to bring into being a paradigmatic case. The details that constitute the paradigm are exemplary in two senses: as an example, they provide a key to the other components of the set, and in their singularity they make sense apart from the group. It is worth noting that the paradigm never pre-exists the group but emerges through the relationship of each singular detail; the paradigm is, in other words, imminent in the detail of clues. The paradigmatic case that archaeology brings forth from cinema in the pages that follow concerns incomplete film, constituted through a set of objects that have in many respects the status of ruins. Treated as unprofitable waste in many contexts, the incomplete film is also the site of a potentiality retained in its state of possibility. The argument that proceeds finds its details in areas peripheral to the film text itself and builds towards an understanding of incompletion in various manifestations. That is to say, incompletion as a figure engages and suspends the laws of use, and the historiographic drive to establish an account of what has occurred. Before embarking on this exploration of incompletion, it may be strategic to set out at the beginning some key features of a philosophical archaeology that may act as particular points of entry.

First, a philosophical archaeology of cinema attends to seemingly insignificant details and is sensitive to the repetitions and reverberations between them. Precisely because they are peripheral, such clues reveal what has been marginalized or rendered more or less invisible through the process of establishing cinema qua cinema. Archaeology points to cinema’s own non-knowledge, the potential that it hides from itself in a zone where half-thoughts, experiments and bits of machinery lie on a workbench. Included in this zone are the material forms of the apparatus that through exclusive attention to the image are rendered insignificant. Exemplary of the excluded features of cinema is the material substrate that supports its functioning yet is dematerialized in our version of cinema: the fabric of the screen, the electronic signal, the gelatin coating of celluloid, the rhythmic motor of the film projector. These materialities are features whose presence is not to be confused with structuralist interventions in cinema. They are rather the waste products of a system which are minimized and when this is not possible, psychically screened out, such as the glitch that disturbs the smooth surface of the image or the fly that infects the shot. Working from these details as signatures, signs that through resemblance carry a charge across historical periods, the archaeologist reveals the paradigm that underpins the functioning of cinema. If then we take the glitch to be the signature as it appears at critical moments in the century of cinema, the paradigm of the glitch requires us to consider what is at stake in its repression, or conversely, what becomes intelligible when it is taken into account.

The second feature of this approach is what we might think of as a revelatory decontextualization. In the practice of resonating the connections and correspondences between details (as it has been sketchily described above), the signature is lifted out of the context of its historical moment in order to appear as such. This attention to a detail bears the marks of an investment close to that of the collector or the bricoleur whose practice, Agamben suggests, ‘extracts the object from its diachronic distance or its synchronic proximity and gathers it into the remote adjacence of history’.3 Agamben makes this comment in a discussion of play, defined as a relationship between objects and human activity that suspends the use value and the temporality of an object. In one sense, the operation of a revelatory decontextualization perfectly describes cinematic montage as it is deployed against the grain of continuity; image sequences are lifted from one temporal–spatial context and set into relation with others to provide a new revelation, and this is perhaps why Agamben finds in Godard’s project of cinematic recombination, Histoire(s) du cinéma (1988–98), the ‘essential, constitutive link between history and cinema’.4 Such a decreation of cinema rubs up against the imperfect question of whether the image is de-essentialized in this relation, that is, does the implied value and meaning of an image become mobile, or does archaeology reveal what has existed (but not been legible) all along.

To an extent, an archaeological method makes of montage a model for the practice of releasing images from the confines of their naturalized location (in the first instance the time and location in which they were recorded, and subsequently their naturalized position within the structure of a film) in order to reveal a relation that otherwise lies dormant. There is a link here to the practice that Laura Mulvey attributes to the pensive spectator of the digital video image who pauses to look ever closer, whose appetite for detail is whetted by the technology that allows one to pause, zoom into the image and scroll back and forth over sequences. There is also, and as Henrik Gustafsson and Asbjørn Grønstad observe, the influence of Aby Warburg’s historian-as-necromancer bringing the phantasmatic image back to life from its seemingly fixed vocation.5 There is in this chapter a particular phantom, the figure of a small girl who comes back to life in the archaeological tracing of her presence across texts and contexts. Released from her dead role in certain sequences of film (and philosophy), she returns as the limit-case of what we can know. Her presence here is instructive in two senses. First, as a child, she is an in-between figure who like the ghost is an ‘unstable signifier’, resistant perhaps to singular interpretation. Second, her form graces the scene of many events in this chapter as an opening onto the unthought or what resides as the underbelly of the intelligible in cinema or philosophy.

This leads neatly to the third aspect of cinematic archaeology which makes legible a potential cinema, one that has not taken place or completely fulfilled the entry criteria to count as cinema. One might take as an example of potential cinema the unfinished film, the incomplete project that remains a fragment either as an idea or a script or as reels of film that have not reached conclusion as a story, nor achieved the necessary closure to count as a commodity. The incomplete film presents other possibilities and iterations as pure fact, a feature that Sarah Keller identifies in Maya Deren’s work as ‘an aesthetic of open-endedness’ that refuses to resolve the tension of oppositions into a neat synthesis.6 Suspended in archives or consigned to the scrap heap (and one may read these as the same fate), unfinished works present not only the potential of cinema to have been otherwise, but its appointment with a future moment. This is an aspect of archaeology that Agamben draws from Benjamin’s messianic thought, a familiar feature that both philosophers identify as an urgent task in the uncovering of relations between things that lie dormant in the ruin in order to arrest the forward march of progress. However, we may also take a less exigent view of this approach to the film fragment in which the form of the incomplete film may be appreciated as it offers itself to archaeological method. As a partial thing, it is always already positioned in relief against the naturalized background (and linear narration) of history and of cinema as an unrolling canon of successful completions in which it fails to register. Against this backdrop the incomplete film demonstrates the great reserve of a cinema that resides as the underbelly to the cinema that we know, a resource that is not only an untapped potential but a figurative presence that troubles the distinction between what has taken place and what has not.

There is a further dimension to an unactualized cinema that engages with potentiality in reverse, or what resides in the slip between im/potentiality. Agamben’s valuing of potentiality as that which is not activated is not only the product of a philosophical engagement with Aristotle’s meditation on what we understand by the term potential, but in its various iterations across Agamben’s work it manifests as a political standpoint: the inhabiting of one’s impotentiality as a mode of resistance to the current imperative to be productive, compliant and identifiable as subjects of a system (or in the case of cinema, the production of film goods for circulation). The exemplary and enigmatic figure of impotentiality who is a constant reference in this regard is the scrivener of Wall Street in Herman Melville’s story, Bartleby, who one day stops working because, he famously says, he prefers not to. His polite statement of a preference to not continue to copy the law may be read as a refusal to reproduce what is. Yet it is Bartleby’s indeterminate formula that will not be confined to systems of will and resistance. For Agamben, Bartleby presents his capacity to not work, to actualize his incapacity as a state to be inhabited (rather than a refusal of an option).7 Bartleby is a figure returned to in the final chapter of the book. Suffice it to say at this point that a further capacity of film archaeology is to value the dreams and fantasies of a cinema that never came to be over the one that we have. To choose not to produce cinema, a non-productivity that takes the course of impotentiality may be manifest in various ways, not only incomplete cinema but also in Pavle Levi’s category of written films that actualized a capacity to not be films.8 In this spirit, archaeology is also the imagining of a cinema that will not come into being, the writing of films that will never be made, the dreaming of works precisely as never to be actualized projects in the first instance.

Agamben’s archaeological method is not, however, without controversy. The methodological approach of Homo Sacer (1998), in particular the third section of the book ‘The Camp as Biopolitical Paradigm of the Modern’, and of the book that followed, Remnants of Auschwitz (1999), has drawn significant critique for its deployment of the figure of der Muselmann, the close to death figure of the concentration camp and the camp itself, as paradigms. The critiques of Agamben’s use of exemplary figures are, in Leland de la Durantaye’s words, concerned with ‘Agamben’s aspiration to present paradigms as both real, concrete situations and representative instances’. Antonio Negri’s difficulty with Agamben’s use of the camp is precisely the exemplary nature of its treatment whereby the Holocaust becomes a model of other instances with similar properties, a form of analogy run wild that reduces the significance of the singular event, whilst Ernesto Laclau finds problematic the speed of Agamben’s movement from a genealogy to a particular instance, which is then granted paradigmatic status. The identification of der Muselmann as the paradoxical figure of testimony who can never bear witness receives critique from Libby Saxton who, in reading Agamben’s text with Claude Lanzmann’s film of the Holocaust, Shoah (1985), warns of ‘the dangers involved in attributing an exemplary or iconic status to any single kind of witness’. If The Signature of All Things engages with these questions, it does so by taking a distance from the role of the historian, positioning its reading as supplementary. He writes, towards the beginning of The Signature of All Things, that his aim is ‘to render intelligible a series of phenomena whose relationship to one anoth...