![]()

Introduction

British theatre, in the last thirty years, has undergone nothing short of a revolution – from a point where the woman playwright was almost an anomaly, to the present, in which more women are writing for the stage than ever before. Never have we had such a prolific and diverse body of their dramatic work as we do now. Many of their plays, like Caryl Churchill’s Top Girls and Cloud Nine, Pam Gems’s Dusa, Fish, Stas and Vi, Charlotte Keatley’s My Mother Said I Never Should, Sarah Daniels’s Masterpieces, Timberlake Wertenbaker’s Our Country’s Good and Sarah Kane’s Blasted, have swiftly become canonical and are now contemporary landmarks by consensus. Women playwrights have broadened the agenda of British drama. Both the form and content of their work have pushed the boundaries of what it is possible to show and tell on stage and our theatre culture is infinitely richer for their contribution. We felt their titanic achievements needed celebrating. We were also curious to discover more about how they craft their plays, why they write, where they find their stories and why, despite their success, they continue to be under-represented in mainstream theatre.

That they are under-represented is acknowledged by theatre managements across the board in Britain. The simple fact is that theatre is still predominantly run by men and commented on by men. The most up-to-date research, Jenny Long’s survey ‘What Share of the Cake Now?’* concludes that only twenty per cent of productions are by women and that the figure drops to fourteen per cent in companies where the artistic director is male. Long’s findings also reveal that women playwrights, proportionally, are less well represented the larger the size of the theatre and the larger the share of the revenue grant. In building-based companies, a marked decrease has been recorded in the number of main-house productions by them, with an increase in studio productions.

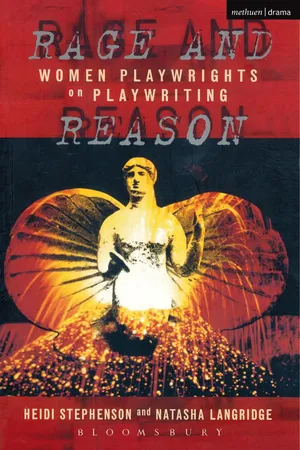

When we started this project, the problem was exacerbated by a phase of ‘lads’ plays. Britain’s powerhouses of new writing, and most notably the Royal Court Theatre, were presenting a seemingly endless barrage of male-orientated work like Tracy Letts’s Killer Joe, Louis Mellis and David Scinto’s Gangster No 1, Jez Butterworth’s Mojo, David Greer’s Burning Blue, Simon Bent’s Goldhawk Road, Kieron Carney’s Afters, Patrick Marber’s Dealer’s Choice, Paul Hodson’s stage adaptation of Nick Hornby’s Fever Pitch, Irvine Welsh’s Trainspotting, William Gaminara’s According to Hoyle, Jonathan Lewis’s Our Boys and Simon Block’s Not A Game For Boys. These plays, which were also often sadly misogynistic, gained a very high profile. What might our women playwrights say about the dominance of and vogue for the work of the male playwright? What might they say about the state of the art or the theatre at large? Did they feel beleaguered or were they optimistic? The title, Rage and Reason: Women Playwrights on Playwriting, emerged as a result of this debate.

The selection process was difficult. From an initial list of seventyfour names, we had to nominate twenty, so that those interviewed would be given the space to express their views. Our main aim was to give a solid sampling of the spectrum of writers whose work is seen in Britain, from the well-established like Pam Gems, Timberlake Wertenbaker and Sharman Macdonald, to the lesser known, like Tanika Gupta (who at the time of her interview was still unproduced). We wanted as diverse a range as possible: writers who scale the heights of the Royal National Theatre and the West End, writers from the Fringe and outside London, performer-writers, young writers and those who started their careers in the sixties and seventies. We chose them because of the vitality and ingenuity of their work and because they each have a unique slant on playwriting, theatre and society.

To retain as much of each playwright’s personality and voice as possible, the interviews are deliberately conversational. All the writers discuss their plays and the myriad of themes and issues which interest them with extraordinary openness and honesty. What we have as a result is a privileged, deeply personal and fascinating insight into their (very different) creative and political thinking. They have put themselves on the line. While not all the playwrights believe that gender or under-representation are central issues, there is general agreement that their work is being marginalised. Most of the writers also believe that national theatre critics not only frequently approach their plays with preconceived ideas, but that the current methods and criteria of theatre criticism are often inadequate. On the face of it there appears to be an unconscious prejudice, which doesn’t feel that unconscious if, as Winsome Pinnock points out, you happen to be a woman playwright. But the reasons for it are complex and, as Timberlake Wertenbaker says, ‘hard to untangle’.

* * *

The task of managing theatres and making programming decisions in these financially difficult times is, Clare McIntyre concedes, ‘a deadly one’ and unless playwrights operate self-sufficiently, as both Claire Dowie and Debbie Isitt have chosen to do by producing their own work, women playwrights find themselves in the hands of the people making those decisions. Whether or not their work gets staged depends on what theatre managements want at the time. Timberlake Wertenbaker mentions the fact that during the mid-eighties the work of women playwrights, especially under Max Stafford-Clark’s artistic directorship at the Royal Court, was in demand, ‘it was a time when women were prominent,’ but that then ‘there was a certain reaction in the press and suddenly they were hungry for a different kind of play: male violence and homoerotica’. The progress towards a more equal balance of male and female work which had been made (Max Stafford-Clark recalls that thirty-eight per cent of his output was by women writers) took a downward turn. ‘Women writers who were prominent in the eighties were knocked out,’ says Vicky Featherstone, artistic director of Paines Plough, who also believes, (as does Max Stafford-Clark), that there’s been a ‘feminist theatre backlash’.

Stephen Daldry, the out-going artistic director of the Royal Court, suggests that the plays of many women writers are not perhaps ‘capturing the Zeitgeist of fashion. Women as an issue on its own’ or ‘work within the context of feminism is unfashionable’, he says. He admits his personal taste does not favour plays which focus on ‘Oh, what happened to socialism? Reflective, wistful plays about the end of an era,’ but adds that this has nothing to do with gender. ‘It’s about men and women, a certain age group of writers’ and that aside of this, ‘The building is not run on my taste.’ He is keen to point out that ‘Statistically speaking, the Royal Court in the last three years has produced more women playwrights than ever in its history’. But he admits that the figures are somewhat distorted because the Royal Court is also now producing more new plays than ever before and concedes, ‘No. We don’t put on enough women’.

Mike Bradwell, artistic director of the Bush Theatre, believes that women playwrights are battling a false perception that their work is ‘breast-beating, worthy or proselytising’ (a negation of the wonderful humour, energy and originality of their work) and that their plays have become identified with ‘an “ism”. Something you do and once you’ve managed to identify and ghettoise it, you don’t have to think about it.’ The media’s promotion of a ‘post-feminist’ era has probably not helped matters, giving theatre managements licence to drop their guard against an over-emphasis of the male dramatic voice. But it seems ridiculous to consider women playwrights either fashionable or not. Gone are the days when their focus was principally on ‘women’s issues’ – although rape, surrogacy, pornography and mother-child relationships, some of the subjects commonly explored in plays by women, were hardly of minority relevance or appeal. But women playwrights have branched out and though, like their male counterparts, they now often write smaller cast plays in the hope of getting them staged, the subjects they deal with – war, class, crime, fate, alienation, power, civilisation, identity – are not marginal, and the way in which they deal with them far from limited or outdated.

Timberlake Wertenbaker believes that one problem may be that plays by women on ‘big’ subjects are not always well-received. It’s an issue that Phyllis Nagy also feels strongly about, that it’s harder for ‘big’ plays to get on when they’re written by a woman and that for too long women’s plays that were ‘allowed’ and encouraged were ‘all about the process of being a woman, as filtered through the eyes of men’. What conformed to a male artistic director’s notion of what women should be interested in got on, she says, and there’s been a resistance to everything else.

Bryony Lavery cites her lack of mainstream success (although the mainstream is not something she particularly admires or aspires to) as having a lot to do with the fact that as a lesbian woman, she cannot be ‘deemed to hold central the hopes and fears of humanity’. As Naomi Wallace points out, universality is still seen as white, male and straight, and Pam Gems feels that we’ve actually slipped back where women writers and universality is concerned. Their work is not yet ‘seen as a metaphor in the sense that if we go and see Hamlet we don’t think, “This is just an adolescent play for men who feel a bit lost,” ’ says Charlotte Keatley. ‘We think “This play is a metaphor for all of us.” ’ She believes that this ‘will change just by having more plays by women’. ‘I think a lot of directors have a very uncomprehensive view of what playwriting can be and what theatre can be,’ says Dominic Dromgoole, director of new plays at London’s Old Vic, ‘and so you tend to get a limited range of enthusiasm. The reason they put boys plays on is because they only see the world as a boy’s world. They read a play by a woman and they don’t get it.’ He emphasises that this is not through lack of goodwill though.

As Sarah Daniels points out, however, theatres in receipt of public subsidy ‘have an obligation to produce new work which reflects a cross-section of themes about different experiences in society’. This has nothing to do with ‘political correctness or positive discrimination’, she says, ‘but fairness.’ She draws attention to the Royal National Theatre which ‘does have the word “national” in the title – so where is half the population?’ And where are the black and Asian writers? ‘It would be exciting if we could just see what’s happening in society reflected on stage,’ says Winsome Pinnock. But ‘it’s not fashionable to ask, “Why haven’t you got any women writers?” ’ says April de Angelis, and ‘You don’t want to force quotas because it should be in spirit that they want to give women writers a voice.’

Richard Eyre, the out-going artistic director of the Royal National Theatre, says that if the appropriate scripts were there, he would put them on. ‘Believe me, if you run a theatre you long for a script. It doesn’t matter if it’s written by a giraffe – if it’s good you want to do it.’ He says he ‘honestly can’t think of a single example of a play by a woman which is generally agreed by readers of mixed gender to be good which hasn’t got on’, adding that where the National Theatre’s main Olivier stage is concerned, Eyre has been ‘trying for nearly ten years to get new writing to put on’, but that ‘there are very few plays that have been robust enough’.

Commercial considerations, as Richard Eyre admits, also come into the equation; raising the question of whether theatres perhaps view the work of women playwrights as more of a commercial risk. The National clearly has a problem on its hands with both the Lyttelton and Olivier stages, but why have so many plays by women, including plays by well-established playwrights found themselves Upstairs at the Royal Court and not on the main stage? Stephen Daldry says that practical obstacles to do with space and programming prevented the sold-out Blasted from transferring Downstairs and that he felt Clare McIntyre’s The Thickness of Skin, for example, was a ‘fragile’ play, better suited to the smaller space. ‘I think you might find that some of the women’s plays Downstairs haven’t found a large, popular audience,’ he says, ‘but I would resist any challenge that we haven’t therefore put them on Downstairs.’

But Pam Gems predominantly writes biographical plays now, partly because it’s so much harder to get an original play produced. ‘Everyone’s concerned with bums on seats,’ says Tanika Gupta. ‘While literary managers might like my writing, artistic directors don’t believe it’s going to bring in the punters’ – a notion she obviously challenges. ‘Theatres are less prepared to take risks with women’s work,’ says Joanne Reardon, literary manager at the Bush. ‘Their work is perceived as more of a risk generally.’ As Mel Kenyon, literary agent at Casarotto Ramsay, points out, ‘This deepseated and erroneous perception not only debilitates female playwrights psychologically, but also has far-reaching financial repercussions. To be crude, the average commissioning fee is a few thousand and a play may take a year to write. If only produced in small spaces, no royalties accrue.’

Yet plays by women do achieve box-office success and are popular with audiences. Sheila Stephenson’s The Memory of Water (a first stage play) played to ninety-eight per cent capacity at Hampstead. Diane Samuels’s Kindertransport transferred to the West End after a recent revival. Sue Glover’s Bondagers sold out at the Donmar Warehouse at the end of an extensive national tour. Yasmina Reza’s Art has been a huge West End hit. Pam Gems’s Stanley is currently on Broadway and Charlotte Keatley’s My Mother Said I Never Should has been so commercially successful that it is still providing her with an adequate income ten years after it opened at the Royal Court.

Sarah Daniels believes there is too much emphasis on the new play having to be a success anyway, although she concedes that theatres do need to keep afloat. But such commercial considerations put a heavy burden on writers which has repercussions beyond the immediate play concerned. As Anna Reynolds says, if your first play is a hit, ‘then great, but you’ve got to come up with another one very quickly. If you don’t, or your second play is not as good or is different, or doesn’t come for three years, then you can forget it.’ Often the best work doesn’t meet with instant commercial success and there clearly has to be some room for ‘failure’. Anna Reynolds adds that although in general we’ve got more new plays now than ever before, it’s at the expense of giving writers time to develop, which has long-term implications for the future of theatre. Because we also live in such a fast-moving media age, as Charlotte Keatley notes, everything, plays and playwrights included, gets hurled aside for the next wave to come in and theatre doesn’t work well at this pace at all.

Theatre managements do have a point, however, when they say that women do not currently submit the number of plays that men do. Graham Whybrow, the Royal Court’s literary manager, says that out of a sample batch of scripts he looked at recently, only 189 out of 1000 were by women and that this necessarily means that the ratio of work selected from them will be lower. Jenny Topper, artistic director at Hampstead Theatre makes the same point – although she believes things are ‘shifting now’, that more plays by women are being submitted. The problem is partly to do with ‘a process of numbers’, as Clare McIntyre acknowledges, but number-crunching both is, and is not, at the heart of the matter. The responsibility lies with theatres too. The theatre establishment expends little energy, in real terms, to welcome new women writers into the theatre or to value the more established playwrights. What would inspire fledgling dramatists to submit plays when they see the work of good, experienced female dramatists frequently being undermined and undervalued, not only by critics, but by theatre practitioners themselves? It’s a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Things are opening up. London’s Bush Theatre, which is now identified as ‘woman-friendly’, currently have seven plays by women in the pipeline, ‘all of which we’ll probably do,’ says Mike Bradwell, who has also commissioned Sarah Daniels, Rebecca Pritchard and Catherine Johnson ‘simply because they are three of my favourite writers’. Not coincidentally, Joanne Reardon cites that in the last six months the number of plays she has received from women has gone up significantly from twenty–thirty to forty per cent. ‘There are an enormous amount of women writing,’ says Dominic Dromgoole, a former Bush artistic director, ‘and they’re writing some of the best work we have. They are generating their own excitement and inspiring others to follow them.’

Women dramatists still need directors to champion their work though. As Jack Bradley, formerly with the Soho Theatre Company and now literary manager at the Royal National Theatre, points out, it doesn’t matter how enthusiastic his department get about a play, if there’s no director behind it, the likelihood is that it won’t go on. This problem is aggravated by the fact that women directors frequently choose to stage the work of male playwrights or go with the classics. There are women ‘who don’t particularly want to see what women are writing’, says Timberlake Wertenbaker, which she suggests may be informed by culture as much as preference, but which has aided the marginalisation of the female voice in theatre. ‘Women directors need to seek out and commit to women writers,’ says Jules Wright, artistic director of the Women’s Playhouse Trust. But women directors still ‘get such an extraordinarily raw deal’, says Lisa Goldman, artistic director of London Fringe theatre The Red Room, that this is sometimes made impossible. She believes that ‘if there was an opening up of opportunity for them’, we would ‘see a change’. Charlotte Keatley adds that it doesn’t help that directors are not given auteur status for directing a new play, which they get more readily with ‘a wild interpretation of Marlowe’. On a challenging note, Richard Eyre offers that if directors Deborah Warner or Katie Mitchell ‘wanted to direct a play by a woman’ at the National Theatre, ‘I’d put it on. They do have a position of strength,’ he says.

Phyllis Nagy believes that the form of women playwrights’ work has also contributed to their under-representation. Unlike most male playwrights who, she says, write ‘thesis’ plays, often asking rhetorical questions in the process, many women have moved away from the traditional and are writing plays which are an open-ended examination and employ sophisticated new structures, far from the linear, limited parameters of the ‘well-made play’. Although not all women playwrights are ‘genuine Picassos’, as Sarah Daniels points out, some directors may be at a loss when it comes to seeing the quality, ingenuity and craft of these plays. Because this work sets a precedent, there may be an artistic fear about approaching it, or a belief that it wouldn’t work. Playwrights have literally been told, ‘This is not a play.’

In all the interviews critics come under considerable attack. The critic versus the artist is, of course, an age-old battle. Playwrights are naturally sensitive to being labelled, defined and judged and that is how critics frame reviews. In an age where a playwright’s success is largely measured by critical approval and, closely linked to this, how well they do at the box-office, critics wield huge power. As Sarah Kane, who became an instant target of the wordwar, points out, critics ‘have the power to kill a show dead with their cynicism’. She regrets that they don’t take their jobs as seriously as the writers ‘they so frequently and casually try to destroy’. Fortunately, the critical vitriol levelled against Blasted (which was variously described as ‘This disgusting feast of filth’ and ‘like having your face rammed into an over-flowing ashtray’) didn’t do it any damage at the box-office – in fact, the play became something of a cause célèbre. But such cases are an exception to the rule and bad reviews usually mean box-office death, which also seems to have a bearing on whether or not the future work of a writer gets staged and where it gets staged.

For women playwrights part of the problem, undoubtedly, is that the vast majority of critics are male and that the same critics have been in their posts for a very long time. As Michael Billington, the Guardian’s chief theatre critic, says himself, ‘We’re conscious t...