![]()

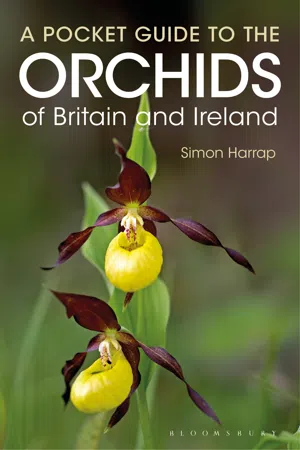

LADY’S SLIPPER

Cypripedium calceolus

IDENTIFICATION

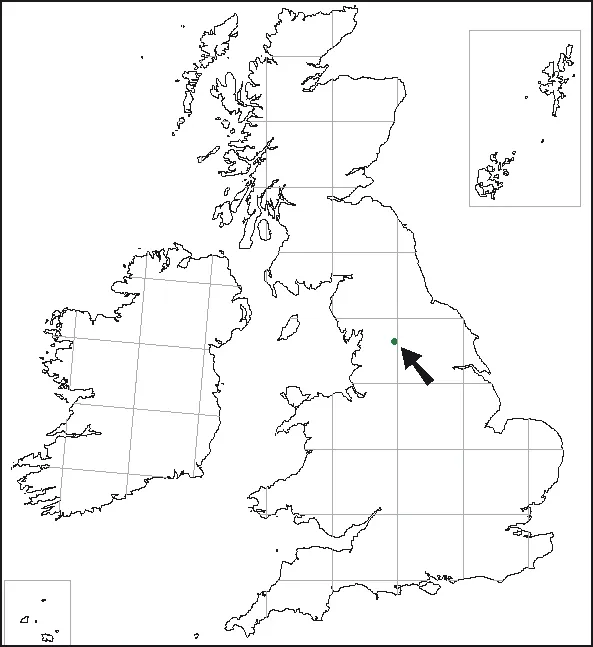

One of Britain’s rarest wild flowers, with just one cluster of plants of native origin surviving at a site in Yorks. Happily, a successful re-introduction programme means that Lady’s Slippers can be seen in flower at several sites in Yorks and Lancs. Height usually c. 30cm and rarely more than 60cm. Unmistakable. The specific scientific name calceolus means ‘little shoe’ and, like the English name, refers to the slipper-like appearance of the lip. SIMILAR SPECIES None. FLOWERING PERIOD Late May–early or mid June. Plants are in flower for 2–3 weeks. Each flower lasts 11–17 days, withering on the sixth day after pollination.

HABITAT

Prefers relatively well-lit areas but likes to have its roots in cool, moist soil. The surviving native plants grow in species-rich grassland on a fairly steep, well-drained, north-facing slope in a sheltered limestone valley. Former English sites were in ash, hazel and oak woods on steep, rocky slopes, always on limestone – recalling the open woodland favoured in Europe.

POLLINATION & REPRODUCTION

Pollinated by small bees, especially in the genera Andrena and Lasioglossum. The flowers do not produce nectar and bees are probably attracted by the flower’s scent, which may mimic the bees’ pheromones (chemical signals that are associated with feeding and mating behaviours), while the colour and markings of the flowers are probably also important in the deception.

A bee lands on the edge of the slipper’s upper opening or tries to land on the staminode (see below), and then falls into the slipper. After a few minutes it tries to leave. The sides of the slipper are very smooth and slippery and the rim curls over and inwards, making escape impossible. The bee can only leave through the small openings on either side of the column where there are small stiff hairs to give it a foothold. These openings are only just big enough for the bee, which is forced into contact with one of the stamens as it makes its escape, picking up a load of pollen. The bee goes on to visit another flower, and when in turn it eventually leaves this its back rubs against the stigma, which projects down into the slipper, and pollen from the first flower is deposited there – the surface of the stigma has minute, stiff, pointed papillae that act as a brush to remove pollen from the bee’s back. As it escapes, more pollen is carried away, ready to be deposited on the next flower and continue the process.

The mechanism is precise and the bee has to be the right size; bees that are too large or too small can escape without pollinating the flower. A wide variety of other insects also enters the slipper but these too are the wrong size and shape and either leave unharmed or may be trapped and die. Self-pollination is unlikely; the bee would have to reverse back into the flower just as it was on the point of escape. In addition, it seems that the flowers are, to a great extent, self-sterile.

The pollination strategy is not efficient and seed set is rather poor with few fertile capsules produced. Bees are attracted to large groups of flowers, especially those in sunlight, but even in large populations in Europe an average of just 10% of flowers set seed. Nevertheless, each capsule contains 6,000-17,000 seeds which may be dispersed by rain – the seedpods seem to close up when dry and open when wet.

Reproduces vegetatively through division of the branching rhizome, and in many populations in Europe this is thought to be more important than seed in the recruitment of new plants.

DEVELOPMENT & GROWTH

The first green leaves are reported to appear in the fourth year after germination by some authors and in the first year by others. The immature plants have a slender stem with1–2 small leaves and may remain in this state for several years. In England a seedling has been noted to flower nine years after it first appeared above ground, and in Europe the young plant takes 6–10 years to produce flowers. Plants are long-lived; many are over 30 years old, with some over 100 years; a life span of 192 years has been determined from the examination of a single rhizome in Estonia.

STATUS & CONSERVATION

Nationally Rare and listed as Critically Endangered: WCA Schedule 8. Formerly found widely but locally in the limestone districts of N England, from Derbyshire to Co Durham, with most records from W and N Yorks. Lady’s-slippers were, however, obvious subjects of curiosity and were picked or dug up from at least the 16th century onwards. In the late 18th and early 19th centuries they were ruthlessly stripped from the wild for horticulture and as herbarium specimens and by the mid 19th century the species was rare. In 1917 it was declared extinct in Britain.

In 1930, Lady’s-slipper was resurrected from the dead when a single plant was found in a remote Yorkshire dale (this plant has survived to the present day). However, the last note of its rediscovery in print was in 1937, and the species slipped from the botanical world’s attention. And, from 14 stems and one flower in 1930 it dwindled to 2–5 stems by the late 1940s and 1950s and seldom flowered: single blooms were produced in 1934 and 1943 but not again until 1959.

Despite the secrecy, in the 1960s word started to get out and the Lady’s-slipper faced the old threat from collectors and a new threat from visiting botanists with big feet and heavy cameras. Indeed, the site was raided and half the plant was removed. The ‘Cypripedium Committee’ was formed in 1970, with representatives from various conservation and botanical interests. Its first priority was to safeguard the sole remaining wild plant, and this has been guarded every year since then – potential visitors are asked to keep away.

With careful protection and habitat management the Yorkshire Lady’s-slipper has slowly increased in vigour, with a steady increase in the number of shoots and flowers on the main clump (which may be just one plant, several clones or even include seedlings). Few or no flowers were being pollinated naturally, however, and hand-pollination began in 1970. This resulted in good seed set and the production of many seed capsules; some are left to mature on the plant while others have been sent to Kew Gardens (two plants taken from wild sites in the early 20th century have survived and are used to cross-pollinate the Yorkshire plant).

As part of the ‘Species Recovery Programme’, organised by Natural England, research began in 1983 at Kew. The fungus that aids the Lady’s-slipper seeds in germination and growth could not be identified, however, thwarting efforts to cultivate plants from seed. After much trial and error, a method of germinating seed in the absence of fungi was developed. This involves supplying the nutrients directly to the seedling in a sterile medium. Although only c. 10% of seeds germinate, large numbers of seedlings can be produced. By 2003 c. 2,000 seedlings had been planted out in 23 locations (17 still had plants in 2010). Survival was not good, however, with slugs and snails a particular problem; 5-year-old-plants have been found to be the best at establishing themselves. The first re-introduced plant flowered in 2000, 11 years after being planted out. In 2009, seed pods formed after natural pollination by insects and by 2015 good numbers of re-introduced plants were flowering, with Gait Barrows NNR near Silverdale, Lancs, the best-known and most accessible public site.

A single plant has also been present at Silverdale for many years, although it is thought that it was planted there in the late 19th or early 20th century; its DNA suggests that it is from either Austria or possibly the Pyrenees. It did not flower for many years but slowly increased in vigour and by 2004 produced nine flowers. Sadly, later in the 2004 season this plant was vandalised and probably partially removed. It survived this thoughtless attack, produci...