![]()

PART I

Contexts

The Draw of Yoga and Meditation

for U.S. Public Schools

![]()

Chapter 1

Education and Law

Court Rulings on Prayer and Bible Reading

There is a perceived crisis in U.S. public education. The first public schools were founded not only to teach practical skills but also to ensure that all children received religious and moral instruction. Today, critics charge that modern epidemics of stress, underachievement, oversaturation with technology, obesity, drug abuse, sexual impropriety, and violence can be traced to a vacuum of moral character—and hold schools responsible. Such concerns are in an important sense nothing new. Although the pace of social and technological change may seem unprecedented, previous generations struggled with wrenching change. Public schools have been idealized as moral guardians—and inevitably failed to live up to ideals—throughout American history.

This chapter explains the educational and legal contexts in which yoga and meditation entered the cultural mainstream. Since the mid-twentieth century, public schools have increasingly been tasked by courts with providing a secular education and by educational reformers with shaping moral character and ethical behavior. Yoga and meditation appeal to educators because they promise not only to enhance physical, mental, and emotional health but also to instill morality and ethics without promoting religion.

The U.S. Constitution formally disestablished religion at the federal level in 1791 with the First Amendment, which stipulates that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” Massachusetts was the last state to follow suit, in 1833. Public schools continued teaching prayer and Bible reading as avowedly nonsectarian methods of cultivating moral character. In the 1960s, the Supreme Court interpreted the establishment clause as prohibiting public schools from endorsing prayer and Bible reading. Over the ensuing decades, the Court developed doctrinal tests of whether school programs violate the Constitution without, however, defining religion or keeping pace with religious diversification. Lower courts and regulatory agencies have developed more robust criteria for determining when moral education bleeds into religion; their findings suggest that yoga and mindfulness meet the same legal criteria of religion as do prayer and Bible reading. This chapter lays a foundation for arguing that even as the disestablishment of Protestant Christianity remains incomplete, other varieties of religious practice are being established, and public schools are crucibles of this change.

Public Schools as Guardians of Religious and Moral Education

The beginning of U.S. public education is often traced to seventeenth-century Massachusetts. Founded in 1630, the Bay Colony passed a school law in 1642. Because “many parents & masters are too indulgent and negligent of their duty” to provide children a “good education,” the law authorized town officials to remove children from their families or apprenticeships and place them in apprenticeships where they would learn to “read the English tongue” and “principles of Religion,” instead of growing “rude, stubborn & unruly.” The Massachusetts School Act of 1647 warned that the “old deluder, Satan,” opposes “knowledge of the Scriptures.” The law required townships to appoint a teacher or grammar school, funded by parents or “inhabitants in general.”1 These early laws foreshadow a long-standing theme in U.S. education: using compulsory education to remedy perceived failures of parents to give children a practical and moral education.

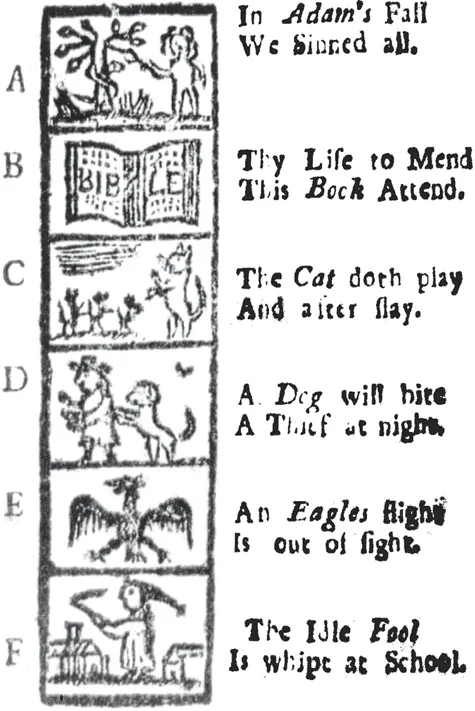

Public education spread slowly and unevenly in the American colonies.2 Between 1820 and 1850, tax-supported “common schools”—designed to educate the “common” people—proliferated. Massachusetts led the way. The New England Primer, first printed in the 1680s, circulated between 3 and 8 million copies by the mid-nineteenth century. The Primer introduced the alphabet with Christian aphorisms—for A: “In Adam’s Fall / We Sinned all”—and taught reading from the King James Bible, Christian prayers and hymns, and the Westminster Shorter Catechism (fig. 1.1).3 Horace Mann, a Unitarian and the first secretary of the Massachusetts Board of Education, from 1836 to 1846, promoted so-called nonsectarian instruction that avoided teaching doctrines of particular denominations, while instilling presumably “universal” (though distinctively Protestant) religious values thought necessary to moral character and civic virtue.4

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) notes that “sect” can be a neutral reference to adherents of any “particular religious teacher or faith” or a negative term for “parties that are regarded as heretical, or at least as deviating from the general tradition.” The term “sectarian” connotes “belonging to a schismatical sect” or being “bigotedly attached to a particular sect.”5 Nineteenth-century educational reformers used “sectarian” as a pejorative synonym for affiliation with a particular tradition—especially Roman Catholicism. Protestants envisioned the King James Bible as imparting nonsectarian moral instruction (despite objections by Catholics who preferred the Douay-Rheims Bible). Mann considered moral education essential for bringing children “cursed by vicious parentage” under “humanizing and redeeming influences.”6 Of particular concern to Mann was the increase in Catholic immigration from Ireland and Germany.

Figure 1.1 “In Adam’s Fall, We Sinned All,” New England Primer, 1721. Courtesy Library of Congress.

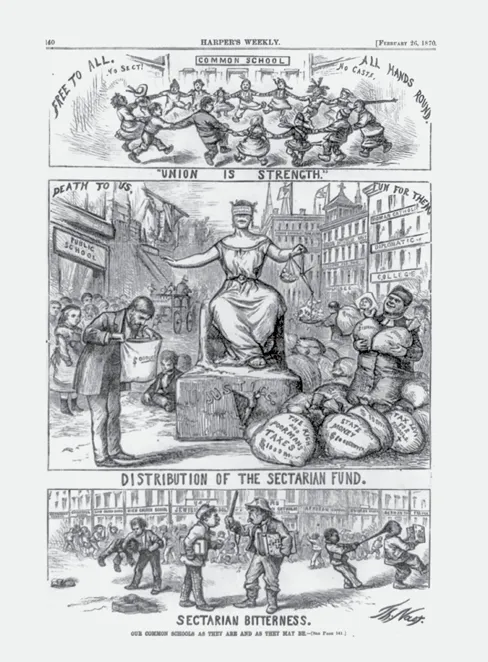

Following the Civil War, Protestant reformers worried about not only Catholic immigrants but also Jewish and Chinese immigrants and newly emancipated African Americans. Protestants idealized common schools as harmoniously assimilating children of all religions, ethnicities, and races. A cartoon by Thomas Nast published by Harper’s Weekly in 1870 imagines “Our Common Schools as They Are and as They Might Be” (fig. 1.2). In the top image, children from various backgrounds hold hands in a circle of “no sect,” “no caste.” In the middle, public-school coffers are emptied to fund “sectarian”—Catholic—schools. The bottom image prophesies the religiously and racially divisive and violent outcome.7

Figure 1.2 Thomas Nast, “Our Common Schools as They Are and as They Might Be,” Harper’s Weekly, February 26, 1870. Courtesy Library of Congress.

Protestants and Catholics clashed repeatedly over the Protestant bias of public schools and Catholic appeals for public funding of parochial schools. In Board of Education v. Minor (1873), the Ohio Supreme Court upheld a school board’s decision to end the Cincinnati “Bible War” by ceasing to read the King James Bible. In absolving schools of legal responsibility to promote religion through Bible reading, the court stopped short of finding Bible reading unconstitutional.8 Cincinnati schools continued using McGuffey’s Readers, 120 million copies of which sold between 1836 and 1920; the 1857 (and later 1879) edition pruned many religious references from earlier editions but still taught virtues of hard work, thrift, and temperance prized by the Protestant middle class.9 States also continued passing laws requiring school Bible reading—with Ohio passing such a law in 1925.10

Early twentieth-century schools taught morality through “character codes.” The widely adopted Children’s Code of Morals, first published in 1916, enumerated ten “laws of right living which the best Americans have always obeyed”: health, self-control, self-reliance, reliability, clean play, duty, workmanship, team-work, kindness, and loyalty—a list of values that reflected and perpetuated Protestant dominance. Schools promoted student buy-in through clubs and team sports, thereby connecting moral with physical education. During World War II and the early Cold War, educators envisioned moral education as defending democracy.11

The 1960s–70s marked a low point for moral education. In the wake of Court rulings barring prayer and Bible reading from public schools, tumultuous cultural upheavals—including desegregation and new immigration—and growing awareness of diversity, educators retreated from controversial values. Many Protestant middle-class parents retreated from urban public schools—into suburban public schools, private Protestant schools, or homeschooling. By the 1990s, a new wave of reformers sought to teach morality sans religion through increasingly varied approaches: values clarification, cognitive developmentalism, feminist ethics of caring, character education, charter schools, social and emotional learning—and yoga and mindfulness.12 This book focuses on yoga and mindfulness because their presumed secularity has received little scholarly or legal scrutiny. Other avowedly secular, yet Christian-premised, character-building programs warrant the attention they have received, and even more careful examination, because the disestablishment of Christianity remains incomplete.

Disestablishing Religion

Prior to the mid-twentieth century, courts interpreted the First Amendment as applying to the federal government but not states—or public schools, since they are locally, not federally, operated. In Everson v. Board of Education (1947), the Supreme Court reasoned from the Fourteenth Amendment (1868) that the establishment clause applies to state and local governments, a principle known as “incorporation.” Everson upheld a New Jersey law using tax money to reimburse parents for busing students to Catholic schools; the Court simultaneously proscribed giving tax dollars to religious schools, since “neither a state nor the Federal Government … can pass laws which aid one religion, aid all religions, or prefer one religion over another,” nor “participate in the affairs of any religious organizations or groups and vice versa.” Everson held that “no tax in any amount, large or small, can be levied to support any religious activities or institutions.”13 More recent court rulings distinguish indirect from direct funding and secular from religious activities. Such distinctions have facilitated government funding of certain programs but do not allow direct government funding of religious activities.14

Courts have been concerned about not only government funding of religious schools but also religious instruction in public schools. In McCollum v. Board of Education (1948), the Supreme Court invalidated a “released-time” program through which privately employed religious teachers offered optional instruction in school buildings during school hours.15 In Zorach v. Clauson (1952), the Court allowed a similar off-campus program.16

In the landmark Engel v. Vitale (1962), the Court ruled that even “denominationally neutral,” “voluntary” public-school prayer violates the establishment clause because the “power, prestige, and financial support of government” exerts “indirect coercive pressure.” The challenged prayer is in full: “Almighty God, we acknowledge our dependence upon Thee, and we beg Thy blessings upon us, our parents, our teachers and our Country.”17 A concurrence by Justice William Douglas denied that “government can constitutionally finance a religious exercise”; an “element of coercion is inherent” in classroom prayer because “every such audience is in a sense a ‘captive’ audience.”18

In the equally momentous School District of Abington Township v. Schempp (1963), the Court disallowed school Bible reading. Public schools must provide a “secular education,” imparting “needed temporal knowledge,” while maintaining a “strict and lofty neutrality as to religion.” Teachers had been required to open the school day by reading at least ten verses from the Bible and leading children i...