![]()

PART

I

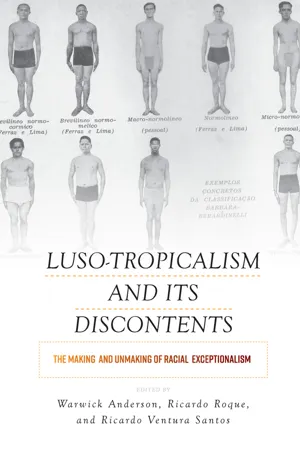

Picturing and Reading Freyre

![]()

CHAPTER

1

Gilberto Freyre’s View of Miscegenation and Its Circulation in the Portuguese Empire, 1930s–1960s

Cláudia Castelo

“Miscegenation” is a key concept in Gilberto Freyre’s thought about the formation of Brazil, Portugal’s “national character,” and the peopling of the spaces of Portuguese colonization. Notions of biological and cultural hybridization, understood as positive processes, permeate almost all his work since Casa-grande & senzala (CGS).1 Published in 1933, the year Nazism gained control of Germany, CGS also was formulated against an international tide of racial segregation in the United States and the European colonial empires. Freyre’s valorization of miscegenation continued through the postwar period, the civil rights movement, and the era of decolonization. And yet, according to Nancy Stepan, if Freyre’s work subverted scientific racism and negative views about race degeneration, it also provided the framework within which a form of eugenics would survive.2

Attempting to reconstruct “twentieth-century networks of racial thought and vision across the Global South, transiting empires and nation-states,”3 this chapter addresses Gilberto Freyre’s ideas about miscegenation and their genesis in dialogue with North American studies of race mixing. It frames the circulation of these ideas in the Portuguese colonial empire as an active and transformative process.4 It further discusses the exchanges and debates that Freyre’s racial conception provoked among scientists and politicians, in two different historical moments: the 1930s to the early 1940s, when Portuguese imperial policy was anchored in white racial superiority and anti-miscegenation was the predominant position among physical anthropologists; and the 1950s to the 1960s, when the Portuguese dictatorship (Estado Novo), confronted with anticolonial contestation and independence movements, adopted multiracialism as its official discourse, and pro-miscegenation stances imposed themselves in the scientific field. Finally, it argues that Almerindo Lessa’s research program on the Luso-tropical mestiço emerged from the questioning of racial prejudices against miscegenation.

Miscegenation in Freyre’s Oeuvre

Freyre’s biography and intellectual networks need to be taken into account if we are to locate and understand the production of his ideas about miscegenation.5 I begin by providing some basic coordinates of his early life, and I will highlight other relevant circumstances and relationships throughout the chapter.6

Gilberto Freyre (1900–1987) descended from wealthy and Catholic sugar planter families of Pernambuco (Northeast Region of Brazil) who had only recently moved to townhouses and entered the liberal professions. His father was a judge and university professor. He had private lessons at home and studied at a high school run by US Baptist missionaries in Recife. At the age of eighteen, he followed an older brother to Baylor University, a Baptist institution in Waco, Texas. After concluding his bachelor’s degree, he enrolled in a master’s degree at Columbia University in New York City. There, he attended courses in history, public law, anthropology, sociology, English, and arts. He became friends with a German colleague, Rüdiger Bilden, a disciple and friend of anthropologist Franz Boas, who was preparing a thesis about slavery in the Americas, especially in Brazil, and Francis Butler Simkins, who was studying the effects of abolition in South Carolina. Under the supervision of William R. Shepherd, a historian of South America, Freyre presented his MA thesis “Social Life in Brazil in the Middle of the Nineteenth Century.”7 He returned to Recife in his early twenties after a European tour, where he was secretary to the governor of Pernambuco and director of A Província, a state-sponsored newspaper. In the mid-1920s, Freyre became involved in the regionalist cultural movement of the Northeast and praised the Afro-Brazilian contribution to the patriarchal origins of the Brazilian culture. The Revolution of 1930 pushed Freyre into exile in Portugal, where he established an intellectual network that would grow in the following decades. At the invitation of Percy Alvin Martin, he was visiting professor at Stanford University in the spring of 1931. Afterward, he visited the “Deep South” with his former colleagues Bilden and Simkins.8 Back in Brazil, he did research in Rio de Janeiro for his first book, Casa-grande & senzala. As we shall see, its publication helped him make contact with North American scholars and activists interested in comparisons between race relations in the United States and Brazil. In the next decades, Freyre would publish prolifically in Latin America, the United States, and Europe; travel often at the invitation of foreign scholars and institutions; and become an internationally recognized and controversial public intellectual.

The issue of miscegenation was not central for Freyre when he was writing his master’s thesis at Columbia in the early 1920s.9 His work was closer to the prevailing ideas on race and the merits of eugenics, far from the ideas he would express in CGS. He wrote of the “improvement” of the enslaved race then underway, and of Argentina as a good model for resolution of the race problem by whitening its population.10 However, in the preface to the first edition of CGS, Freyre claimed:

It was my studies in anthropology under the direction of Professor Boas that first revealed to me the Negro and the mulatto for what they are—with the effects of environment or cultural experience separated from racial characteristics. I learned to regard as fundamental the difference between race and culture, to discriminate between the effects of purely genetic relationships and those resulting from social influences, the cultural heritage and the milieu. It is upon this criterion of the basic differentiation between race and culture that the entire plan of this essay rests, as well as upon the distinction to be made between racial and family heredity.11

Maria Lúcia Pallares-Burke views this attempt to trace a direct affiliation with Boas and the US cultural anthropology skeptically. She establishes the contribution of several authors from diverse geographies and disciplines to the gestation of CGS, namely Edgard Roquette-Pinto, Lafcadio Hearn, G. K. Chesterton, Alfred Zimmern, Herbert Spencer, and Franklin Giddings. She also reveals the surprising role played by Bilden: Bilden was Freyre’s “flesh and blood” discussion partner, who probably also introduced him to Roquette-Pinto in Rio de Janeiro in 1926 while doing research for his PhD on the role of slavery in the history of Brazil. Boas’s influence on Freyre’s “culturalist turn” must have also been an outcome of Freyre and Bilden’s interaction.12 In 2012, Pallares-Burke extended her arguments about the repercussion of Bilden’s ideas on Brazilian miscegenation through Freyre’s work.13 In the preface to the first edition of CGS, Freyre acknowledges that he benefited from Bilden’s “valuable suggestions.”14 He owed to Bilden the positive conception of miscegenation as something good, beautiful, and enriching, and the idea about the distinctive characteristics of the Portuguese colonizer, including the alleged Portuguese aptitude for miscegenation. Throughout the book, Freyre quotes or refers to Bilden’s texts and manuscript in progress, to which he had firsthand access.15 Freyre continued to value Bilden’s influence in his own work into the early 1940s:

I am indebted to Rudiger [sic] Bilden, now a contracted professor at Fisk University,16 and, like me, a former disciple of anthropology of Professor Franz Boas, at Columbia University, to suggestions for the study of Brazil’s social history, compared to other American areas; suggestions as valuable as those I owe to Professor Franz Boas himself.17

From this point, however, Freyre tended to forget his intellectual debt to Bilden, who never finished his PhD or produced a book from his research.18

It is difficult to determine whether Bilden discussed with Freyre the works that were published in English in the first decades of the twentieth century intended for a black audience—works that argued that slavery in Brazil created the conditions for cordial relations between the races that obviated the color line.19 Bilden certainly moved in anti-racist intellectual circles, however,20 and Freyre cited in CGS, among others, The Negro in the New World (1910), by the British colonialist and explorer Henry Johnston; South America: Observations and Impressions (1914, rev. ed.), by the British historian and politician James Bryce; The Negro (1915) by W. E. B. Du Bois (founder and president of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People [NAACP] and director of its journal, The Crisis); and The Conquest of Brazil (1926), by Roy Nash.21 After graduating in social sciences from Columbia University in 1908, Nash was secretary of the NAACP and worked on its anti-lynching campaign. In the early 1920s, he traveled around Brazil for three years and spent a summer in Portugal, the “old metropole,” to write a book on Brazil’s history. Joel Elias Spingarn—literary critic, civil rights activist, second president of the NAACP, and Nash’s friend and editor—commented on the book in correspondence with Freyre.22 Nash’s book had an underlying US-Brazil comparison, presenting Brazil as a promising “social laboratory”:

Except the Portuguese colonies in Africa, Brazil is the one country in the world where fusion of Europeans and Africans is going on unchecked by law and costume. More than in any other place in the world, readmixture of the most divergent types of humanity is there injecting meaning into the “egalité” of Revolutionary France and the “human solidarity” of philosophers and class-conscious proletarians.23

CGS described the colonial condition in Brazil in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries—more precisely, in the sugar-producing Northeast—under the plantation economy based on slavery and structured around the casa-grande and the patriarchal family headed by the senhor de engenho (sugar mill owner). According to Freyre, the specificity of Brazilian society resulted from frequent crossbreeding between white, black, and Amerindian, in both biological and cultural terms. Published when deterministic racial models were still very popular among Brazilian scientists,24 CGS built a positive image of racial mixing within the patriarchal and slavery society during the colonial period, highlighting African and Amerindian contributions to Brazilian national identity. Its arguments generated wide discussion within and outside the academic world, and they exerted an enduring impact on Brazil’s self-perception and its external appraisal. The new insights in CGS called into question ideas that were commonly accepted in the United States and Europe in the interwar years, such as the inferiority of the black people, African heritage as an obstacle to progress, and the idea of “whitening” as a solution to the problem of racial degeneration.

Freyre held that the Portuguese national character resulted from the nation’s hybrid ethnic origins, location between Europe and Africa, and history of contacts with Muslims and Jews in the Iberian Peninsula during the first centuries of Portuguese statehood. The recurrent f...