1

WHAT IS A CHILD?

The time is now. Arm your women and children against the infidel!

Osama bin Laden, 2001, Tora Bora, Afghanistan

What is your most lofty aspiration? Death for the sake of Allah!

Kindergarten verse at a Hamas school, Gaza City

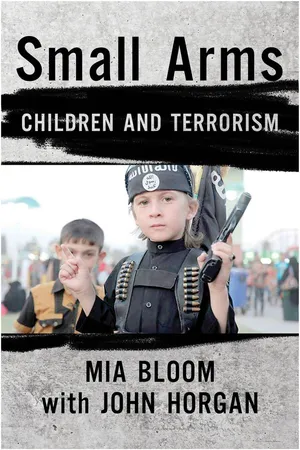

Children in violent extremist movements, disparagingly referred to as “child terrorists,” are not born. Rather, they are made, and they learn to want to be a part of a violent group, either with or without the knowledge and support of their families.

On July 4, 2015, the Islamic State’s (IS) propaganda channels released their most disturbing video to date. It began with claims of IS’s “heroic” successes on the battlefield against the regime of the Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad. In the video, adult IS fighters march bloodied and barefoot Syrian Arab Army prisoners in and out of jail cells. A caravan of Toyota trucks flying IS flags gather, as a nasheed (hymnlike musical prayer) begins. The colonnades of the ancient ruins of Palmyra, a two-thousand-year-old UNESCO World Heritage Center that served as the backdrop for Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, are draped with the distinctive black-and-white flag. The twenty-five soldiers march onto the stage and fall to their knees, awaiting execution. The camera pans across the packed coliseum, whose audience includes adults and very young children.

In the next shot, twenty-five children march out as the nasheed commences again. IS calls these children Ashbal al-Khilafa, or Cubs of the Caliphate. The children sport matching uniforms, and some even smile for the camera. The condemned men (alternately referred to as either murtadd, nusayriya, or kaffir1), no longer blindfolded, look on with panic. After an announcer reads Qur’anic passages that describe both mercy and retribution, the camera pans across the faces of the children and those of the men condemned to die—such that the viewer can see the horror in the condemned men’s eyes and the hollow stares of the youth. The Syrian soldiers understand precisely the fate that awaits them. The children, looking over their right shoulders (for a signal), raise their handguns in unison, and then each child shoots a Syrian soldier in the head. The scene is looped several times, lest anyone doubt that the children actually pulled the trigger on command. The final scene shows the aftermath: bodies with limbs akimbo, blood seeping into the sand.2

IS (also known as the Islamic State in Syria and Iraq, the Islamic State in Iraq, and the Levant, or Daesh, the Arabic acronym) uses children in ways that are markedly different from those of other terrorist groups and recruits them in ways different from how African child soldiers were recruited in the past. In previous conflicts, children were in the background, aiding behind the scenes or sneaking through enemy lines. In Iraq, children aided the insurgents fighting American soldiers and even operated on the front lines, though only occasionally and only in a handful of cities. But the trend of militarized youth grew during the Iraqi insurgency, with children playing a variety of roles in the battle of Fallujah, from snipers to armed fighters.3 In January 2007, children played key roles in the kidnapping of Sunni merchants from Sinak Market in Baghdad, by engaging Iraqi police firing automatic weapons and forcing them to flee.4

According to the United States Marine Corps, “U.S. forces faced child soldiers in the past (Germany, Vietnam, Somalia, and Afghanistan), [and] it is inevitable that they will face them again in the future.”5 But in Palmyra, the victimized soldiers were not foreign “occupiers” and the children were not targeting US troops. These were children who had been groomed and brainwashed to carry out the most egregious acts of violence against their own countrymen.

Many of us have become accustomed to reports of child suicide bombers in places such as Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan, and Nigeria. According to the research we have conducted for this book, the median age of suicide bombers overall has been declining steadily, especially with the increased use of child bombers by IS and its affiliated groups (for example, Boko Haram). More children are participating in hostilities, and in more nefarious ways.6 In the 1990s, child studies researchers observed that “more children and youth are bearing arms in internal armed conflict and violent strife than ever before.”7 In their analysis of child soldiers, Vera Achvarina and Simon Reich argued that this trend challenged the claim that international norms had positively influenced the rules of war.8 An April 2010 news report by the journalist Erik Stakelbeck prophesized a future worsening of the problem of children not just as child soldiers but in terrorist organizations: “Islamic terrorists are always looking for new ways to escape detection and carry out their attacks. One of their latest ideas is using children as suicide bombers.”9 Our study of the Islamic State’s Cubs of the Caliphate certainly dispels the myth that war is being fought more civilly; the chapters that follow will demonstrate how the problem is getting worse and metastasizing from one conflict and region to the next.

While the use of child soldiers in Africa is well documented and organizations such as the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) have garnered international condemnation for recruiting children,10 misconceptions persist about how children become involved in terrorist group violence or are recruited as front-line activists. The questions we answer in this book focus on the extent to which children are recruited and used differently from adults in terrorist groups. Over the past three years, the world has watched in horror as Syrian and Iraqi children, once just passive observers of extreme violence, have become fully committed activists personally involved in hostilities. These Cubs of the Caliphate have gone from viewing videos of beheadings, to leading prisoners onto a stage for execution, to passing out the knives used for execution, to carrying out the executions or beheading themselves (as was the case in Palmyra).11 And since January 2015 they have acted as suicide bombers and inghemasi—commandos who fight and die alongside adults in high-risk missions in which their deaths are premeditated.

This book explores the extent of children’s involvement in terrorist groups and examines their transition from victims to perpetrators, while demonstrating the interchangeability of these roles. It approaches children’s involvement in terrorism from two complementary perspectives, one macro and the other micro. The macro lens examines under what circumstances and why terrorist organizations recruit children. This approach complements theories of international relations and civil war. For example, are children recruited because of a loss of manpower when adults are killed in battle, or during periods when adults cannot be mobilized? Alternatively, do children possess unique skills that adults might lack; that is, can they bring some new or innovative comparative advantages to the terrorist group, such as being able to gain access to sensitive or civilian targets that adults would fail to access? To this extent, this book borrows a framework from economics to determine whether children are a “complementary” or a “substitute” good for terrorist groups.12

We know little about the recruitment of children into terrorist organizations. Studies of child soldiers have traditionally approached the issue from a child rights framework, focusing on estimating the numbers of children involved, recounting individual experiences and stories, describing the legal instruments against their use, and evaluating disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration (DDR) programs.13 According to the American University anthropologist Susan Shepler, we know more about the demobilization, rehabilitation, and reintegration of child soldiers than about why militants or governments use children in the first place.14

Is it conceivable that organizations might prefer to mobilize children because they are cheaper, more malleable, or easier to control than adults? This was certainly the case in Mozambique with the resistance group RENAMO (Mozambican National Resistance Movement), who evidence suggests preferred children to adults. One deserter conceded, “RENAMO does not use many adults to fight because they are not good fighters. Kids have more stamina, are better at surviving in the bush, do not complain, and follow directions.”15 From the 1980s on, RENAMO recruited children as young as six, seven, and eight years old, who were literally “programmed” to feel no fear or revulsion for the massacres and, according to Alex Vines, thereby “carry out these attacks with greater enthusiasm and brutality than adults would.”16 This preference for very young recruits was not limited to Mozambique. A senior officer in Chad’s army explained, “Child soldiers are ideal because they don’t complain, they don’t expect to be paid, and if you tell them to kill, they kill.” (emphasis added)17 The same was true for the fifty-two-year civil war in Colombia.

We are witnessing something comparable in Syria and Iraq, where a generation of children has been entirely desensitized to extreme violence. According to a report by the international nongovernmental organization (NGO) Save the Children, children display signs of “toxic stress.” The 2017 report explains that children have witnessed family members killed in front of them, dead bodies and blood in the streets, and bombs destroying their homes.18 Joby Warrick summarizes the conflict as consistently pushing the boundaries of horror, and notes that children are not safe from being targeted:

As ISIS dispatched suicide bombers into sports arenas and community soccer games as well as mosques, cafes, and markets even Iraqis inured to bloodshed expressed shock when an ISIS recruit drove an explosives laden truck into an elementary school playground in Nineveh Province in October 2013, killing thirteen children who were [playing] outside for recess.19

Other children shared stories about family members shot by snipers, blown up by landmines, or hit by explosives as they fled.20 “The children are so deeply scarred by memories of extreme violence they are living in constant fear for their lives, unable to show emotions, and suffering from vivid ‘waking nightmares.’”21

In conjunction with examining why terrorist groups recruit children, this book also examines the microlevel processes: how are children recruited and socialized into violence? Are children always coerced to participate, through institutional mechanisms (youth wings, summer camps, exposure to media aimed specifically at them) that facilitate their entry into violence and terrorism? Are the ways in which children are mobilized into a terrorist organization different from the ways in which adults are recruited, and if so, what distinguishes this process from the (stereotypically) coerced recruitment of child soldiers? This book focuses on the social ecologies of children’s lives: parents, families, peer groups, religious leaders, and other community-based institutions, and how structural conditions pressure children to participate in hostilities. We also examine the varying incentives related to environmental (structural) conditions that might make involvement more or less attractive to children and their families.

The presence of children on the battlefield has additional unintentional consequences for the civilian population and the organization of power structures in a society. Using children for militant activities challenges existing age hierarchies and reflects the breakdown of the family unit.22 In prisons, IS allegedly uses children to select who lives and who dies, at the same time empowering the children (who are made to feel that they have the power over life and death) and further humiliating and emasculating the adults, whose fates are decided by eleven- and twelve-year-olds.

Children’s recruitment differs from that of adults in the degree to which they consent. Children may not have the same option to refuse mobilization into a terrorist organization as an adult does. In fact, actual accounts of children’s recruitment by terrorist groups vary along a spectrum between co-optation and coercion. In some cases, like many involving child soldiers, children are forcibly taken from parents against their will, while in other instances they gravitate toward involvement over time, with the consent or even encouragement of their parents. Jamie Dettmer summarizes this spectrum:

Since 2014, youngsters who joined ISIS were often coerced to do so in different ways, ranging from being cajoled by parents, to kidnappings from orphanages. Some parents were eager for at least one of their children to enlist because of the monthly payments ISIS paid the families of cubs; but others did so because they agreed with the terror group’s ideology.23

We must consider that varying degrees of coercion play a role in how and why children become involved in terrorism and that each case might include a mix of inducements, luring, and coercion. Children may be forced or duped. The United Nations ruling regarding the international...