![]()

Introduction: Section 1

Context and Exposition of the Vida

The saint’s life entitled Compendio de la vida ejemplar de la Venerable Madre Sor Teresa Juliana de Santo Domingo (Salamanca, 1752) is the foundational documentary evidence in the case for beatification of the eighteenth-century African religious, a nun, Sor Teresa Juliana de Santo Domingo (c. 1676–1748), who was named “Chicaba” at birth.1 As such, it is the most significant and comprehensive source of information about her. The Vida (Life) is one of the elements prescribed by the directives of the Council of Trent for the process of canonization. In the eighteenth century, these items included (1) the preaching and distribution of a funeral oration, (2) the publication of a longer narrative of the venerable candidate’s life and a detailed account of her spirituality (i.e., a hagiography), and (3) the pictorial representation of the holy person.2

Juan Carlos Miguel de Paniagua, a Theatine priest, delivered the eulogy at Sor Teresa Chicaba’s funeral mass, which he then expanded and published as Oración fúnebre en las exequias de la Madre Sor Teresa Juliana de Santo Domingo (Salamanca, 1749).3 Three years later, he sent to press a comprehensive account of her virtuous life. What he had heard of the African sister from devoted visitors to her convent, his fellow priests, and members of her religious community must have captured his imagination and prompted him to establish a relationship with Chicaba during the last months of her life. This familiarity with her story qualified him to become her official hagiographer, though he had been neither her confessor nor spiritual director, as was common for most biographers. As the full title indicates, the Vida is a compendium or compilation of texts, which Paniagua said he had culled from her poems, her autobiographical writings, and their extended conversations, which he used to expand the Oración fúnebre.

According to the narratives of both the eulogy and the hagiography, Sor Teresa de Santo Domingo was born in the West African territory known to seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Spanish and Portuguese navigators and slave traffickers as La Mina Baja del Oro.4 The text of the Vida opens with a lament about how few facts the author can muster concerning Chicaba’s childhood given how young she was—about nine years old—when abducted into slavery, but it also reports the names of her mother and brothers, which suggest that her people were Ewe.5 She was initially sent to the island of São Tomé, where she was baptized and given the name “Teresa”; from there, she was shipped to Spain, surviving illness during the arduous first leg of the Middle Passage. Perhaps her youth or her enslavers’ belief that the manillas (gold bangles) she wore were the signs of her exalted social status among her ethnic group convinced them that she might bring a special profit in the Spanish market. In Spain, Juliana Teresa Portocarrero y Meneses, then the Duchess of Arcos, purchased Teresa Chicaba. When she married Antonio Sebastián de Toledo, the second Marquis of Mancera, she brought Chicaba to her new household in Madrid.

As a member of the Manceras’ retinue, Teresa Chicaba must have habituated herself to the piousness of her mistress and developed an intense spiritual life that in time became her key to freedom. Though the Vida is at pains to depict her status in the religious, aristocratic household as almost that of a privileged foster child, the narrative relates several accounts of her mistreatment by others who were in service to the Manceras, particularly by a cruel and abusive governess.

At the behest of the marchioness, who died in 1703, Teresa Chicaba was freed to enter a convent.6 The Dominicans of La Penitencia in Salamanca accepted her after she had been rejected by several other monasteries because of her skin color. Race put her at a disadvantage within the highly stratified social hierarchy of monastic houses of the era, even within her own religious community. The sisters first received her as an aspirant. Then, at the command of the local bishop, they granted her some vaguely defined status, probably as a secular member of their order. Later, the local bishop presided over what the Vida describes as an irregular profession of some kind: the ceremony was performed earlier than church canons prescribed, and her contract with the convent does not clearly specify her status in the order. Sometime later, a Dominican friar regularized her vows and designated her as a “white-veiled” member of the order.7 Her duties were to perform menial labor in the convent.

Despite her initial marginality in the community, Teresa Chicaba eventually gained recognition as a healer and a sister with prodigious religious gifts. The annuity bequeathed to her in the marchioness’s will, as well as donations from people who sought her prayers, allowed her to establish ascendancy in the monastery among nuns who could make their professions only thanks to her financial help with their dowries. Sor Teresa Chicaba died on December 6, 1748. Notwithstanding her inferior status in the order, her piety, her acts of charity, her mystical experiences, and her fame as a healer or miracle worker moved her order soon after her death to begin the process for her beatification.

As a biography of a saintly African woman, the hagiography exhibits the two cultural backgrounds of its subject—African and European—by occasionally reflecting a syncretization of Catholic piety with religious practices retained among some peoples of the African diaspora. The Vida also combines the attributes of two types of texts that trace part of their origins in the oral accounts of their protagonists and associates: the hagiography and the as-told-to slave narrative later found in the Americas. As a consequence, these genres produce questions concerning the relationship between authorial and informant voices.

Paniagua did not publish his life of Sor Teresa Chicaba in a vacuum. The Vida and the earlier Oración fúnebre were probably part of a two-pronged mutual effort by the nuns of La Penitencia and the Theatine priests to promote the canonizations of both Teresa Chicaba and her Theatine confessor and spiritual director, Jerónimo Abarrategui. First, it is possible that the Dominicans in her community had sensed the presence of an unusually saintly person among them—an occurrence they had occasionally detected since the Middle Ages—and had therefore requested that a priest interview their African sister. Second, by the time Paniagua took on the task of writing Teresa Chicaba’s hagiography, he was the rector of San Cayetano, the college of his order in Salamanca, and as such, he was invested in the canonization of Abarrategui, the founder of that institution. In addition, his friend Diego Torres Villarroel, a secular priest and one of the most popular writers in Spain during the period, was working on the hagiography of Abarrategui. Also, Paniagua must have been aware of another association between Chicaba and his order: the Marquis of Mancera was a protector and patron of the Theatines and, according to the Vida, several priests of this order became Teresa Chicaba’s spiritual directors during her enslavement in Madrid.8 Therefore, by promoting Chicaba’s cause, Paniagua advanced both the case of Abarrategui and the prestige of his own order, which had benefited from the patronage of a grandee of Spain. This might explain why the Dominicans did not commission a member of their own order to write Chicaba’s life, or why a Theatine chose to take on the task.

The Oración fúnebre was a text that circulated among Paniagua, Torres Villarroel, and others. Torres Villarroel refers to Sor Teresa Chicaba twice and at great length in his hagiographic vida of Abarrategui.9 This saint’s life appeared in the same year (1749) that Paniagua published Chicaba’s Oración fúnebre. In addition, Torres Villarroel mentions the Oración fúnebre as he summarizes Teresa Chicaba’s life in Abarrategui’s life story. His purpose in writing about Chicaba was to demonstrate the extent of his priestly subject’s spiritual influence; thus, she becomes an example of a saintly nun who followed Abarrategui’s spiritual direction (Torres Villarroel 57–58). A similar summary of her life appeared the same year in the Acta Capituli Provincialis provinciae Hispaniae Ordinis Praedicatorum (Acts of the Chapter of Toro).10 Paniagua was therefore involved in a typical effort to promote a member of his order by contributing to a corpus of literature that included Abarrategui’s spiritual entourage. By documenting the holiness of Teresa Chicaba, a woman whose soul was his spiritual responsibility, he enhanced Abarrategui’s saintly reputation. As a sign of their close association and mutual holiness, Torres Villarroel mentions Sor Teresa Chicaba as one of the people who had a vision of Abarrategui’s death and ascent to heaven (107–9).

The Oración fúnebre in honor of Sor Teresa Chicaba must have been quite a success, for Paniagua records in his dedication of the Vida that the text circulated throughout Spain and went as far as the Spanish American colonies. Besides the Oración fúnebre and the Vida, there is extant at least one other document written in the decade or so after Sor Teresa Chicaba’s death in an effort to promote her beatification. In 1757, a priest from Zaragoza, Luis Soler y las Balsas, wrote a poem entitled Vida de la Venerable Negra, la Madre Sor Theresa Juliana de Santo Domingo, based on the Oración fúnebre.11 He composed this work in seguidillas, a popular stanza form that became a favorite mode for conveying other hagiographic material.12

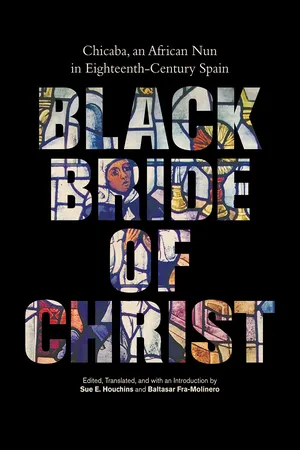

Also, her community commissioned two portraits of Teresa Chicaba. One picture, probably now lost, depicted her standing next to Abarrategui. This painting was clearly part of the joint effort to promote their causes. The other portrait is still on display in the convent of Las Dueñas in Salamanca (Figure 1). It represents Sor Teresa Chicaba in the habit of the Dominican order, kneeling in adoration before a monstrance that contained a Communion host or wafer. In this picture, one of her favorite saints, Vincent Ferrer, to whom the Oración fúnebre and the Vida are dedicated, watches over her.13 The legend at the bottom of the portrait explains Teresa Chicaba’s African origin and name. The text of this caption reiterates the same details of her life that appear in Torres Villarroel’s book and in the minutes of the Dominican chapter (assembly) of 1749, as well as at the end of the document of her profession.14 Along the bottom of the extant portrait is the following obituary, serving as a kind of abbreviated biography or hagiography:

True portrait of Mother Sor Theresa Juliana de Santo Domingo, daughter of the King of the Lower Gold Mine, Professed Tertiary in the Convent of Saint Mary Magdalen, popularly known as La Penitencia, of Dominican nuns in Salamanca. A woman in whom grace performed repeated miracles, and through them took her away from Guinea, her homeland, and directed her to this Convent where she lived, according to general opinion, in evident sanctity for many years. After a full life in high esteem she rested in peace on the sixth day of December in the year 1748 at the age of 73.15

A similar short text was appended in a different hand under Sor Teresa’s signature at the bottom of her official so-called act of profession (Appendix 2),16 and it is preserved to this day in the museum of Las Dueñas, the monastery of the second order Dominicans in Salamanca, where Sor Teresa Chicaba is now buried.17

The signature on this act of profession is a small but crucial piece of evidence of Chicaba’s literacy. The name she signs is “Soror Teresa de Sto. Domingo,” which she separated and divided between two lines of text. This same signature appears on a letter written to a Father Figueroa in 1730, twenty-six years later, and in this case, the same hand produces the entire text of the document (see Figure 2). This is the only extant autograph example of her writing.18 Had Chicaba been unable to sign for herself, her act of profession would most likely have recorded it. She would have signed her vows with a cross, and a notary would have indicated that she could not write, which was customary with legal documents. Also, it is highly unlikely that the same person would have signed for her in the same manner on two different occasions separated from each other by two decades. The only difference between the two signatures is a rúbrica (flourish), which is present in the act of profession but not in the more private, informal autograph letter. The presence of the rúbrica, a frequent addition to official documents, indicates quite clearly that Teresa Chicaba was skilled and experienced in the use of the ink pen, for a person merely able to sign her name would not have attempted this embellishment. Clearly she was aware of the protocols of signing official documents.

The autograph letter further substantiates our contention that Chicaba was literate because it contains certain spellings that are consistent with a person who spoke with an Andalusian accent, the dialect typical of the region where she spent her first years in Spain, before she moved with her mistress to Madrid.19 It is doubtful that a nun from the area around Salamanca (as were most members of La Penitencia) would have written like a southerner or tried orthographically to reproduce Chicaba’s pronunciation.20 Importantly, the text of the Vida itself further asserts her full literacy—the ability both to read and write—when it relates her capacity to set up and sing from the Roman and the Dominican versions of the Divine Office.

Also, among the important papers pertaining to Chicaba is the record of the transportation of her body during the Napoleonic occupation of the city in 1810 from La Penitencia, which was scheduled for demolition, to the convent of Las Dueñas, the second order Dominican nuns cloistered in the same city.21 This document and her bodily remains are still in Las Dueñas. That her community decided to remove Chicaba’s body to the security of the consecrated ground of another Dominican house attests to the high regard in which her sisters in both communities held her.

The effort to have Chicaba canonized continues today. Not long ago, the Dominican convent of Las Dueñas in Salamanca created a small museum for the edification of the laity as well as the veneration and promotion of Chicaba’s cause for sainthood. The exhibit, situated on the second floor of the spectacular Renaissance cloister of the convent, houses two personal relics of Chicaba’s, a clay drinking cup with an inscription in Arabic, and a shoe reported to be hers. It also displays the extant portrait as wel...