We have all taught an Evie and it is all too easy to lower our expectations and allow her to be present in our lessons but rarely truly challenged. Frankly, in a lesson on the English Civil War, it is easier and requires less conflict to ask her to draw and label a picture of a member of Cromwell’s New Model Army than to think about, and explain in writing, the reasons for Parliament’s military success. The first may fill thirty minutes of a Friday period 5, while the second is going to take substantial time, effort and struggle. A caveat to this is that an adapted version of the first activity may contribute to a successful outcome in the second. Explaining the reasons for Parliament’s success is an example of what might be termed critical thinking; however, we cannot think critically or deeply about history without the necessary subject, or domain, knowledge to think with. Therefore, we must not fall into the trap of assuming that we should make our history lessons more challenging by moving more swiftly to critical thinking about the event, person or theme. We must first seek to develop our students’ understanding, ensuring they have a secure base of knowledge about these topics.

In essence, history is a knowledge-based subject. We want our students to gain a deep knowledge and understanding of the past, and we should not confuse increasing challenge with neglecting the storytelling element of our discipline in order to jump straight into critical thinking or analysis. For students to be able to explain the New Model Army’s success in the latter stages of the English Civil War, knowledge of the army’s training and weaponry would be essential and time must be devoted to learning this detail. What is not essential is finding the right shade of brown to colour in a tunic, or selecting a particularly satisfying name for our freshly sketched soldier.

In the adapted version of Evie’s task, she may spend a few minutes labelling a pre-drawn version of the soldier before adding her own line of explanation for each feature about how it would help him to be successful on the battlefield. Work done before, during and after this task would give her the context to make confident and well-informed observations and would define the success of this exercise. This can be achieved through the explanation, modelling and questioning strategies discussed in the later chapters of this book.

A transformational moment for me when clarifying what everyday challenge meant, was hearing Professor Robert Coe’s keynote speech at the 2016 SSAT and The Prince’s Teaching Institute conference. He posed three questions to the delegates:

Question two particularly resonated with me. When I thought of my Evies, could I honestly say I regularly planned for them to be stuck? Or, more often than not, was I planning for them to be occupied? For the most part, the strategies in this chapter focus on how we can set our expectations high, up the challenge and, as a consequence, increase the amount of time our students spend thinking hard about history, struggling where necessary – while still keeping our sanity and an ordered classroom.

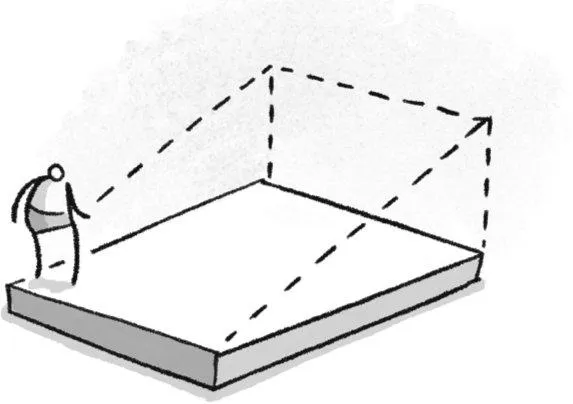

To add some underpinning theory to this, if we think about learning as happening in the three zones outlined in the model that follows, challenge is about getting our students into the struggle zone as regularly as possible. Learning is unlikely to happen in the comfort zone as they are not thinking hard enough about the material for it to be retained. Equally, once the challenge gets too high, students enter the panic zone and will shut down to what we are trying to teach them. This is in large part due to cognitive load theory, as when we offer students too much information their limited working memories will be overloaded. Cognitive science teaches us that our working memory only retains information for about thirty seconds before it is forgotten and that it can only cope with three to five different stimuli at a time. The information that we attend to and think about in our working memory will then transfer to our long-term memory, which is the storehouse of concepts, vocabulary and procedures. We ultimately want the content of our teaching to end up secure in long-term memory as it is from here that students can retrieve that knowledge. Therefore, when the challenge becomes too high the working memory becomes overloaded and the knowledge is not retained.

The lesson here is that it is important not to bombard students with sources of information, particularly if these compete for their attention. Therefore, if you are attempting to teach the Peasants’ Revolt by explaining the events through storytelling, while also projecting a complicated slide on the board that contains a long piece of text to read, questions to answer and several images to analyse, students will have too much to cope with and will fail to retain the knowledge. It would be better to complete your explanation and then unpick a key image, before introducing the text for them to read in silence and then, finally, ask students to complete the written outcome you desire, based upon the questions.

Preparing for our students to get stuck and having the strategies to unstick them is a long-term venture and can best be encapsulated by the principle of challenge.

1. Prioritise Learning over Performance

Using plenaries at the end of lessons to prove to an observer that the students have made progress has always been a flawed measure. The reason why is that all they prove is surface learning, or performance, rather than deep learning. Learning is mysterious, liminal and invisible, and an individual lesson is the wrong unit of time over which to judge it.

Recently I taught the Hungarian Uprising to a Year 10 class and the lesson went particularly well. I got the level of challenge right and the students dutifully struggled through the concepts and activities. At the end of the lesson I checked for understanding through questioning. All the questions I asked – from eliciting small factual details, such as the number of Hungarians killed, to checking more complicated concepts, such as the reasons for the USSR’s military intervention – were correctly answered. It would be very easy at that point as history teachers to pat ourselves on the back and think, “Job done, they got that.” However, the sad reality is that if I then failed to return to that topic regularly over the following weeks and months, faced with a question about it in the Year 11 mock exam, for the majority of those students all of that knowledge would have disappeared. They would not know who Imre Nagy was if he came into the exam hall and shook their hands, which is admittedly unlikely on several counts. Therefore the questioning at the end of the lesson revealed performance, not learning. It is learning we are seeking and so we should always think first about the macro rather than the micro; with regular opportunities to revisit, revise and embed learning. In order for challenge to work it must be integrated into a stimulating curriculum that supports long-term retention of knowledge. Individual challenging lessons may be great in themselves but will not achieve our overarching aims.

2. Space It Out and Keep Coming Back

If the challenging curriculum we design is to work effectively we have to take into account the likelihood that students will forget what we teach them if we do not return to it regularly. As historians we tend to like chronology, timelines and stories. Everything in its proper place and taught in the correct order. However, this classic approach to the history curriculum may not be the most effective.

If we move through an epic topic like Germany, 1918–1939, constantly teaching new material, the reality is that however challenging we make the lessons, students will eventually forget what we’ve taught them if we never revisit the content. In the nineteenth century, psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus conducted a series of experiments, the results of which revealed a trend which has latterly been termed the...