1

In the Beginning

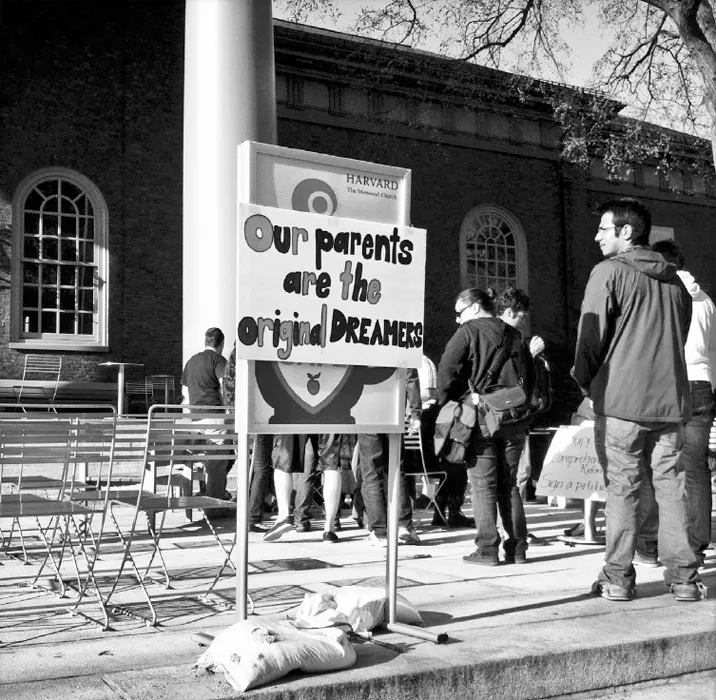

Sign posted during an undocumented “coming out” event at Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, April 2013.

It would only be a few weeks.

That’s what Hareth Andrade-Ayala’s parents told her when they planned the trip to Washington, DC. Eight-year-old Hareth and her little sister would travel from La Paz, Bolivia, with their grandmother and grandfather. Their parents would join the girls later.

Hareth’s grandparents had lived with the family as long as she could remember, always game for her bits of theater, jokes, and dances, all the stuff her parents were too tired to sit through. She’d traveled to visit relatives with them before. This would be another one of those adventures.

The night before they left, Hareth’s mother tucked her elder daughter’s favorite books into the suitcase. Betty Ayala had bought the books on layaway with money from her accountant work at city hall. One book was filled with jokes, another with tongue twisters. The last book was titled Why Is This So?

Betty paused on that one. “¿Por qué es así?” was one of Hareth’s favorite phrases. Already it was tough for Betty to answer all her daughter’s questions. Her own mind twirled around the biggest “whys”: Why leave? Why risk everything?

Hareth’s father, Mario Andrade, had a few classes left before he finished his architecture degree at the university and was already helping build a multiple-story commercial building in La Paz. Betty, who had left her job at the municipality after Hareth’s younger sister Haziel was born, kept the books for Mario’s projects. Compared with many in Bolivia, they were doing okay.

At first the idea really was just a vacation. Mario’s parents regularly visited his sister, Eliana, who’d moved to the United States in 1994, had obtained citizenship, and now lived in Maryland. They could take the girls with them this time, let Hareth and Haziel practice their English. Mario and Betty applied for their daughters’ visas. The request was easily granted.

But even then, Betty was forming a backup plan. Famous for its jagged Andes and Quechua people in bowler hats and flounced skirts, Bolivia also held the distinction of being South America’s poorest country. Social unrest had been creeping like a stubborn vine across the mountains in recent years, and now it was spreading its tendrils from the remote hills down to the streets.

The government’s efforts to eradicate coca farming in the late 1980s and 1990s, with help from the US government, had left thousands of small farmers desperate and without any alternative sources of income. Then came the water wars. In 2000, mass protests swept Cochabamba, the nation’s third largest city, after the government gave a private international consortium control of its water service.1 Bolivians were outraged that a foreign company had come to control what they viewed as a basic public good. When price hikes quickly followed,2 it was too much. The protests multiplied and the unrest spread,3 leading to food shortages in other cities.

By the spring of 2001, the unrest found its way to Betty and Mario in La Paz. Activists began demonstrating in the streets against similar water privatization. Thousands of miners planted themselves in the heart of the city, demanding the government help revive their industry. They set off explosions at a courthouse and marched toward the Congress.4

Mario and Betty lay awake at night. If they waited until total chaos hit, they would be among thousands seeking to escape. They could try to get a US residency visa by entering the American government lottery, which allotted each nation a set number of visas annually, but fewer than a hundred such visas were usually granted to Bolivians each year.5 They could ask Eliana to sponsor Mario on a sibling visa, but that would likely take at least a decade. No, they would apply for tourist visas just like their daughters. They would send Hareth and three-year-old Haziel ahead. They would stay behind, sell their belongings, and pack up the house. In a month or so, they would join their daughters. And if things went well, they would stay and eventually seek permanent US residency. It was a risk giving up Mario’s budding professional career, saying a permanent good-bye to many friends and family, and likely having to wait years to receive legal permanent immigration status in the United States, but those were risks they were willing to take. Waiting to see if things got worse was scarier.

“Be good,” Hareth’s parents told her at the airport. They would see each other soon. Hareth frowned, puzzled by her mother’s serious expression. Of course they would see each other soon. At security, Betty stopped and buried her face in the girls’ hair. Mario pulled them in to his broad chest, his hands big enough to clasp each daughter’s head as he gently bestowed kisses on them.

They let go, and Hareth held tight to her grandmother’s hand, while her grandfather carried Haziel in his arms. Then the excitement of a plane ride wrapped around her and skipped her feet down the airport corridor. On that August day, as Hareth pressed her small face against the plane window, her heart thumped against her ribs. Her grandmother gave her a spoonful of cold medicine to help her sleep through the seven-hour flight, and Hareth nestled against her grandfather. The plane lifted off over the rust-colored homes, stacked against one another on the hillsides of La Paz. Behind them, the snowcapped Andes offered a silent good-bye.

They landed first in Miami. A summer storm had delayed their next flight, and they would have to spend the night there before the final leg of their journey to Maryland where “La Tía Eli,” as Hareth called her, lived, so they set off in search of a nearby hotel. Hareth’s grandmother took the girls to the bathroom.

It was only a few moments before Hareth looked around and didn’t see her sister. “Haziel?” she called. “Haziel?!!!” One minute Haziel was there. The next, she had vanished. Hareth’s breath caught in her throat.

Hareth couldn’t speak English, nor could her grandparents, but they had landed in Miami, where that wasn’t a prerequisite. They scanned the faces of the travelers striding past them, wondering whom they could approach for help. Her grandparents hesitated.

Hareth did not. She approached a man in uniform. Please, she said, looking up at him. We’ve lost my sister. Can you help? They went from one official to another. Hareth and her grandmother were in tears. How could she have disappeared so quickly? Their minds jumped to the possibilities: a little girl lost in a vast airport, or worse. They searched up and down the cavernous corridors until at last they found Haziel, happily playing with airport security guards, who had found her.

As they boarded their flight the next day, Hareth clutched her sister’s hand tightly in hers. More unsettling than Haziel’s disappearance was her grandparents’ reaction—how uncertain they’d seemed in the midst of the emergency. Hareth silently swore she would never again lose Haziel. She would take charge of her family from now on.

It was a relief to see their aunt waiting for them at Baltimore-Washington International Airport. On the way to her house, the girls spotted a McDonald’s. They knew little about this new country, but they recognized the golden arches. “McDonald’s!” they screamed. Eliana dutifully pulled into the parking lot. Inside the restaurant, Hareth demanded her aunt translate every menu option, every detail of the kids’ meal, before making her selection. But her throat closed when she tasted the hamburger with its strange pickles and onions. All she really wanted was the plastic toy. Afterward, the girls marveled at the restaurant bathrooms, which didn’t even smell.

At Eliana’s, they settled into a routine. Hareth and Haziel shared a room with their aunt, and they moved from Maryland to Virginia, where Eliana enrolled Hareth in an elementary school. The school was near the dry cleaner’s where Eliana worked in Washington’s wealthy Woodley Park neighborhood, up the street from the National Zoo. Hareth practiced her English watching Sesame Street and Full House at home or at the cleaners while her aunt sorted suits and silk blouses. Occasionally they watched Spanish-language news together, but mostly Hareth paid little attention to the political debates quietly brewing over what the country should do about immigrants like her. She missed her parents, but her grandparents and her aunt assured her that they would come soon.

Looking back later, Hareth would struggle to reconcile that first uneventful dinner at McDonald’s and those early months at school as she awaited her parents, with the radical changes that would follow in her life, eventually leading her onto the national stage. Hareth would grow up part of a generation of young immigrants often collectively known as the DREAMers: kids raised in a country whose language and culture they identified with, whose pledge of allegiance they recited every morning in school—and yet a country that sought to render them akin to ghosts the moment they became adults, making it impossible for most to seek a college education, work legally, or have any official say in the political system. But these teens refused to become ghosts, to hide as their elders had. And ultimately, despite their immigration status, or in part because of it, many have become among the nation’s most politically engaged young citizens—in all but name.

Some, like Hareth, have fought for change overtly, sharing their stories with countless other youths and lawmakers, advocating for immigration reform. Others have taken a stand through the simple act of demanding to be recognized for their contributions to the country. Some have worked within the system, and some have pushed up against it. No one person has led the fight, nor have these young immigrants done it alone. But over the course of two decades, they have effectively shaped the debate over who should be considered an American, forcing the United States to recognize the millions of people working in the shadows to keep this country’s economic engine humming. They have demanded difficult conversations be had about the future of our country, and they have faced opposition in the nation’s most powerful Washington corridors. In truth, it remains to be seen how their story will end and how many will be forced to leave their adopted country before it does, but in many ways, the millennium is where their story begins.

HARETH AND HER GRANDPARENTS arrived in the United States just as the government began toughening sanctions against those who entered the country illegally or overstayed their visas. Soon it would become nearly impossible for most undocumented immigrants in the country to legalize their status. Even those who could apply to become permanent residents often had to go back to their home country, where, in a Catch-22, they generally faced a ten-year ban on returning. Hundreds of thousands of people, if not millions, who in the past might have had another option to adjust their status, now faced the permanent threat of deportation.

In the fall of 2000, nearly a year before the Andrades arrived, Josh Bernstein sat tensely through a panel in a drab classroom at the Catholic University of America in Washington, DC, listening to lawyers describe the upswing in immigration cases. The Catholic Church had been helping children who had come to the United States unaccompanied, as well as immigrant children who’d been abandoned, neglected, or were fleeing abuse. If the children could document their cases, they were allowed to stay. The problem was the growing number who couldn’t provide evidence, who didn’t have witnesses lined up or police reports from their home countries. The speakers described children, many from war-torn Central America, who had been allowed to remain in the United States as their cases wound through the courts, only to turn eighteen, lose legal protection as minors, and likely face deportation back to countries they barely knew.

Josh ran a small office in the nation’s capital for the Los Angeles–based National Immigration Law Center, a nonprofit group dedicated to helping low-income immigrants. The son of liberal Jewish parents who’d met on a picket line during the civil rights movement,6 Josh couldn’t help finding parallels between that struggle and the challenges facing undocumented immigrants in Los Angeles. Josh’s personal and political life had further intertwined in the 1980s, when he fell in love and married an undocumented woman from Mexico whom he had met at a local café.

In the last year, he’d been flooded with requests for help from desperate immigrants facing deportation. In addition to the unaccompanied-minor cases he received, there were calls from teachers and social workers about children whose families were intact but who were now coming of age and discovering that despite growing up in the United States, they had no legal status and could be picked up and deported at any moment.

Those kids who managed to fly under the radar through high school graduation found themselves unable to work legally, ineligible for in-state college tuition, and unable to afford the tuition otherwise. In many states, they couldn’t even fill out the college application because they lacked the proper legal documents. Any work had to be paid under the table. It was as if, upon graduation, they reverted to being phantasms.

As the law center’s chief policy analyst, Josh worked to enlist the support of sympathetic lawmakers. With his round face, pale blue eyes, wire-rimmed glasses, and soft Valley-accented voice that seemed to turn every statement into a question, he seemed more suburban rabbi than immigrant champion, but his unassuming nature disarmed the lawmakers to whom he appealed.

There were certain things senators and congresswomen and -men could do: private bills they could file, simple phone calls they could make that could tip the scales for one specific child or another. But there were only so many of those favors to go around; it was like asking someone to inflate a thousand inner tubes with just his own breath. And as the case list grew, Josh found his contacts running out of air.

THINGS WERE GETTING BAD in Mexico. Land reform had enabled agribusinesses to buy up huge tracts of farms, sending many smaller growers to the cities or al Norte for work. The 1994 North American Free Trade Agreement had enabled US corn producers to flood the Mexican market, providing increasingly tough competition for the remaining small farmers. Then came more blows—the devaluation of the peso and massive inflation—culminating in basic economic meltdown. Mexicans increasingly decided to seek their fortunes in the United States.

Among those headed north was Dario Guerrero. He and his wife, Rocio, grew up in merchant families in Mexico City, where Dario’s parents owned a furniture store and Rocio’s parents sold construction materials. As an adult, Dario ran a small offshoot of the family business. Rocio managed a clothing shop up the block, taking their new baby, Dario Jr., to work with her during the day. Next door, her brother sold bathroom interiors. They tried to make it work even after the peso dropped in half and inflation jumped 50 percent.

But when the assaults began, Dario began to rethink things. First, they came to Rocio’s store and held a knife to her stomach as they grabbed her cash. Soon after, the girl in her brother’s shop next door was assaulted as she worked. Rocio heard the cries from the other side of the wall. Too terrified to react, she cowered in her own shop, praying she wasn’t next. The police were little help, arriving only if her husband took them a bottle of wine. As the economy grew worse, and people grew more desperate, nightly newscasts were increasingly filled...