![]()

PART I

Creating Money from Nowhere

![]()

CHAPTER 1

How Did We Get Here?

“And you may ask yourself—Well ... how did I get here?”

(Talking Heads, Once In A Lifetime. Remain In Light)

“Unconventional monetary policy.” You might have heard it many times, but it’s a misleading term.

What mainstream media and consensus call “unconventional” is and has been the most conventional policy of the past 600 years: to try to solve structural imbalances and macroeconomic problems through inflationary measures; creating money out of thin air.

Printing money, of course, is not exactly what the major central banks have been doing. What they have been doing in the past eight years is more complex. The idea of using the apparently endless balance sheet of a nation’s central bank to absorb government bonds and similar instruments to free up banks’ capacity and allow them to lend more to Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) and families has a logic—but only when it is a temporary measure to provide liquidity, reduce unwarranted risk perception, and return to normal. The idea seemed good at the time. Until the “temporary” and “extraordinary” measures became the norm.

And therein lies the problem. Monetary policy is nothing more than a short-term tool, but it does not solve structural imbalances. At best, as Mr. Mario Draghi, president of the European Central Bank (ECB), reminds every time he speaks, it is a measure that buys time and allows governments and other economic agents to sort out problems, mostly derived from excess debt and poor capital allocation.

But even the most carefully planned program creates significant perverse incentives. The most obvious one is to make the same mistakes repeatedly.

By the end of 2015, more than 25 central banks in the world were following the same path: “Easing,” or, lowering interest rates and increasing money supply.

After eight years, more than $24 trillion of fiscal and monetary expansion, and over 650 rate cuts, the balance is certainly disappointing. It was very easy to get in the liquidity trap of endless cheap money, and in this book, we will explore how to escape from it unharmed.

Let us look at the results achieved from years of stimulus and hundreds of rate cuts:

At 3.1 percent, the year 2016 saw the poorest global GDP growth since the crisis.

The U.S. growth is the poorest of any recovery and half of its potential, with labor participation at 1978 levels.1

World trade has fallen to 2010 levels.2

Global debt has ballooned to an all-time high of $152 trillion, or 225 percent of world GDP.3

Rise in government debt as a percentage of GDP from 2007 to 2015:

-

United States, from 64 percent in 2007 to 105 percent in 2015

-

China, from 35 to 45 percent

-

Eurozone, from 65 to 97 percent

-

Japan, from 183 to 230 percent4

Meanwhile, the largest bubble in bonds ever seen was created, with $11 trillion of negative-yielding bonds issued and high yield at the lowest rate in 30 years.5

Yet the media calls this a success.

Are these the results anyone would have expected from a massive monetary stimulus? Clearly not.

While media and consensus economists were calling for devaluation policies to increase exports, these have stalled;6 and the boost to global growth ended at the weakest level in decades.

But ... How Did We Get Here?

Through the same measures that we have used to “tackle the crisis.”

We got here doing exactly what the media is offering as “the solution”—a massive expansion of credit and money supply. If we ask any economist in the world about the origins of the financial crisis, they will immediately answer pointing out to “excess leverage” and “too much risk” as the causes. However, this is partially true, because those were effects, not causes.

The origin of this crisis,7 like every other financial crisis in history, was the massive increase in risk generated by manipulating the amount or price of money; in this case, it was lowering interest rates artificially.

Crises are not generated in assets that the public or economic agents perceive as risky, but in those where the consensus is that the risk is very low. In 2008 it was housing; in 2016 it is bonds.

In the origin of all financial crises, we see the stubborn determination of governments and central banks of ignoring economic cycles as if monetary policy will change them—the magical idea that imbalances will be solved by perpetuating and increasing those same imbalances. Excess debt and misallocation of capital are not problems that will be solved by lower interest rates and more liquidity; in fact, those measures simply prolong the same course of action by economic agents.

Low interest rates and high liquidity fuel the fire; they don’t extinguish it. At best, the measure should be aimed at helping deleverage and cutting the chain of risk taking while the economy recovers, but that does not happen. The incentive for misallocation of capital is too large.

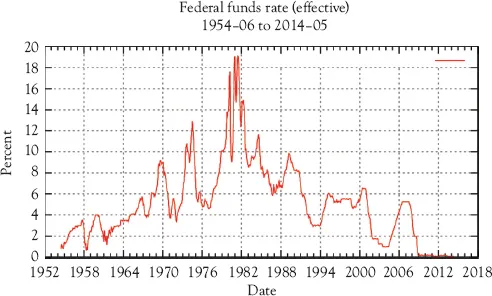

Figure 1.1 Historical chart of the effective Federal Funds Rate. From 2001 to 2006 interest rates were dramatically lowered

Creating money, lowering interest rates, forcing credit growth at any cost, and increasing money supply are the same measures, just with different tools. In the years 2001 to 2008 the excessive risk taking was promoted by central banks and governments’ lowering interest rates dramatically;8 the conduit for debt-fueled growth was the private sector, with the financial system as the facilitator. See Figure 1.1. Money was too cheap to ignore.

After September 11, 2001, the U.S. Federal Reserve began to inflate credit supply to try to prevent an economic crisis. Low interest rates, which reached around 1 percent in 2003, made commercial banks and other financial agents have excess cash to lend even to individuals with poor solvency ratios (what we called “subprime”).

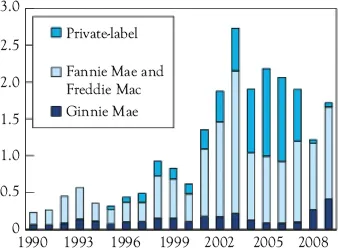

The largest originators of these loans were two public-sector entities, Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae. See Figure 1.2. Were the banks reckless and taking unwarranted risk? No. The public and expert opinions were that housing was a safe bet. The safest bet, actually. It was a low-risk and very liquid asset that could be sold at a higher price quickly if the borrower could not meet payments.

Figure 1.2 Value of mortgage-backed security issuances in $trillions, 1990 to 2009

Source: Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association (SIFMA) statistics.

The process by which this credit was generated violated the traditional principles of bank management. Or did it? Banks invested in long-term assets (mortgages) the funds they received in the form of short-term debt (public deposits), hoping to meet these short-term obligations by repaying in the interbank money markets. The reason to do this was the widespread perception that the asset was liquid and very profitable because the underlying (real estate) demand was virtually inelastic and prices would not drop, and, if they did, it would be by a very small amount.

The result of it was a brutal credit expansion fueled by the relentless message that houses were a secure and ever-rising asset. Like all bubbles, this one lasted longer than any skeptic could have imagined, making even the most doubtful of analysts question their position. Rising demand for credit meant higher housing prices, which in turn led to more risky mortgages and the prospect of higher returns. Liquidity was such that economic and financial agents would absorb any asset, no matter how speculative it was, because the risk seemed inexistent and prices kept rising. It seemed there was never enough supply of home and risky assets.

Household debt went from 100 percent of disposable income to 160 percent, and suitably, house prices doubled.9

By 2004 many borrowers began to experience difficulties in repaying their loans, but demand remained healthy and house prices were slowing down, but not falling. The bubble was bursting, but the consensus was that it was no real issue. Credit for housing exceeded 20 percent of all outstanding credit. However, by early 2007 reality started to kick in and the chain of nonperforming loans started to explode, as household debt exceeded disposable income by more than 60 percent and thus began a series of massive defaults.

These defaults sank the market value of all the related mortgage loans. Given that banks had to pay for their short-term debts while a substantial part of their income disappeared, a liquidity crisis was generated. As the market value of subprime loans fell further, the liquidity crisis deepened, so much that banks themselves did not want to lend to each other.

The risk of a run on the banks increased, as customers and the general public feared for their deposits.

Central banks decided to come help contain the fire they had created with a massive liquidity injection.

Central banks behaved, again, as the “Pyromaniac Fireman,” as I always say.

I remember when Christine Lagarde, then head of the IMF said, “Central banks have been the h...