![]()

1 Evolution and Diversity of the Flora

Land plants arose almost 500 million years ago (Ma). Those with a vascular system (lycopods) appeared at least 450 Ma, followed by the ferns with true leaves rather than scales at least 400 Ma. Seed-bearing plants originated about 430 Ma giving rise to the gymnosperms about 330 Ma, including the cone-bearing cycads in one clade (phylogenetic group) and the conifers in another.

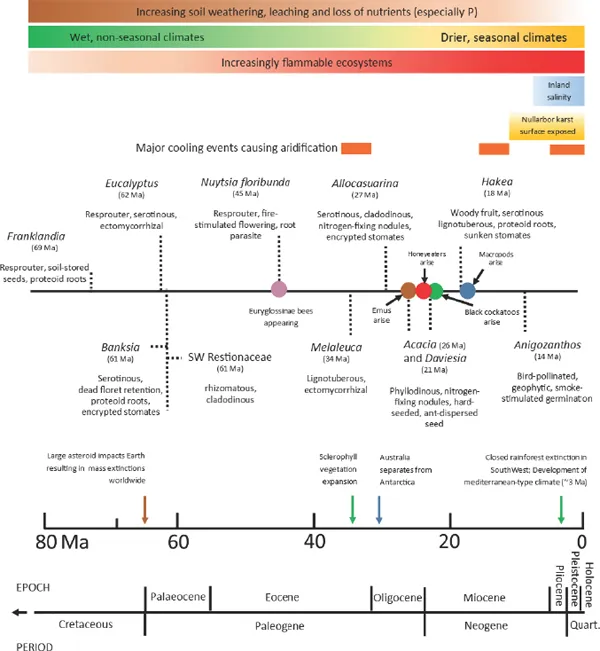

The latest research based on rates of change in DNA structure (the molecular clock) puts flowering plants arising at least 134 Ma but it may have been up to 248 Ma depending on the true affinity of different fossils and the accepted rates of molecular change and whether a group is only recognised once it starts to separate into its daughter groups (called the crown) or at its base where it remains undivided or only a single-ancestor can still be identified at the molecular level (Clark et al., 2011). This puts angiosperm origins in the Permian Period, or as early as the Ordivician, much earlier than once thought. Nevertheless, once the angiosperms appeared they gradually outcompeted all previously existing groups of plants, certainly by the end of the Cretaceous, 65.5 Ma. This was apparently due to their rapid growth rates and superior colonizing ability. Speciation of the SouthWest angiosperm flora was particularly rapid during the Miocene to Pleistocene, a time of great climatic upheavals with a general drying and cooling trend from 15 Ma (Fig. 1.1), including a period of severe aridification 2−5 Ma (Dodson & Macphail, 2004). Many plant lineages that were once widespread within temperate Australia, now have separate taxa in the SouthWest and southeast/eastern Australia because of the biogeographical barrier imposed by aridification and the elevation of limestone sediments in the current Nullarbor Plain, beginning 14 Ma (Crisp & Cook, 2007).

1.1 A Radiating and Hyperdiverse Flora

Elements of the Australian flora were already present in the Upper Cretaceous, 90 Ma, mostly confined to rainforest dominated by conifers but also in fire-prone, sclerophyll pockets (see Fig. 1.5 – Proteaceae phylogeny). The large asteroid that struck the Earth in the Gulf of Mexico 65.5 Ma, causing an abrupt end to the Cretaceous Period, was an important event for the world’s biota, including the SouthWest. Within 4 million years (61−62 Ma), key taxa in the SouthWest flora such as Banksia (Proteaceae), Eucalytpus (including Corymbia) (Myrtaceae) and the Australian Restionaceae emerged (Fig. 1.1). All these groups are adapted to nutrient-impoverished soils and highly fire-tolerant. Eucalypts are at present the dominant overstorey species in temperate Australian woodlands and forests and they further enhanced the flammability of the flora through the aromatic oils in their leaves and stems though it is thought that initially they evolved to deter herbivores (Crisp et al., 2011). Eucalypts also have a distinctive epicormic resprouting structure (Chapter 2; Burrows, 2013) that remained unchanged throughout the subsequent Cenozoic Era to the present time (Crisp et al., 2011).

Fig. 1.1: Appearance of extant species-rich and iconic SouthWest taxa in Australia since the late Cretaceous Period compared with the occurrence of biotic and environmental agents of selection. Euryglossin bees and honeyeaters are pollinators of the flora (Chapter 8) whereas black cockatoos have influenced the evolution of woody-fruited species (e.g. Hakea) (Chapter 11). Geological time compiled from The Geological Society of America Geological Time Scale (2012, v. 4), and key events obtained from Byrne et al. (2014). Formation of Nullarbor Plain and aridification events since 35 Ma obtained from Crisp & Cook (2007). Information obtained from time-calibrated molecular phylogenies described in Crisp et al. (2004) [Allocasuarina]; Vidal-Russell & Nickrent (2008a) [Nuytsia]; Hopper et al. (2009) [Anigozanthos]; Prideaux & Warburton (2010) [Macropods]; He et al. (2011) [Banksia]; Crisp et al. (2011) [Eucalyptus, Melaleuca]; White et al. (2011) [Calyptorhynchinae cockatoos]; Miller et al. (2013) [Acacia]; Almeida et al. (2012) [Euryglossinae bees]; Litsios et al. (2013) [Restionaceae]; Baker et al. (2014) [emus]; Joseph et al. (2014) [honeyeaters]; Franklandia and Hakea from Fig. 1.5.

Tree root-parasites are basal within the hemiparasitic Santalales order and the best known in the SouthWest is the monotypic Nuystia floribunda (Loranthaceae) that arose 45 Ma during the Eocene (Fig. 1.1). This relict is unique among the Santalales in having wind-dispersed fruits (all others have succulent fruits that are a feature of rainforest species), precocious fire-stimulated flowering from fireblackened stems, tough, semi-terete leaves, and rhizomes reaching 100 m in length. These features suggest that at least parts of the SouthWest during the Eocene had a highly seasonal climate and were subject to frequent fire (Lamont & He, 2012). Parasitism in the Loranthaceae evolved from terrestrial to aerial 28 Ma, with rapid diversification occurring during the Oligocene, an epoch of global cooling and temperate woodlands and grasslands (Vidal-Russell & Nickrent, 2008a). Today Loranthaceae is dominated by aerial hemiparasites, though only Ameyma and Lysiana are present (and widespread) in the SouthWest (Chapter 5). Both genera are pollinated by honeyeaters (Meliphagidae) that originated 23.5 Ma and radiated strongly between 15 to 5 Ma (Joseph et al., 2014; Fig. 1.1). The frugivorous mistletoe bird (Dicaeum hirundinaceum, Dicaeidae) is a major seed disperser (Yan, 1993a), although this species did not colonise Australia until the Pleistocene, possibly as late as the Holocene (Reid, 1987), arriving from New Guinea and the surrounding islands (Nyári et al., 2009) and was already adapted to its mistletoe berry diet. This bird never reached Tasmania.

The Ecocene also saw the origin of solitary stingless bees in the Australian endemic subfamily Euryglossinae (Colletidae) (Fig. 1.1) and the Australian biodiverse subfamily Hylaeinae (48-54 Ma) (Almeida et al., 2012) that are important pollinators of small-flowered species in Australia. Emus (large flightless bird) (Dromaius novae-hollandiae: Dromaiidae) appeared 27 Ma (Fig. 1.1) and became important long-distance seed dispersers.

Major taxonomic groups were well established in the Australian flora by the time Antarctica split from Australia as it pulled north, beginning in the West in the early Eocene and finishing with Tasmania during the early Oligocene, leaving the flora to radiate in isolation from other continents, as the climate became colder and drier with Australia’s drift into the mid-latitudes. The Casuarinaceae (Allocasuarina, Casuarina and Gymnostoma) radiated about 47 Ma (Crisp, Cook & Steane, 2004), with the Allocasuarina/Casuarina clade developing about 39 Ma, with their leaves reduced to minute scales, encrypted stomates hidden within cladodinous grooves, and serotinous woody cones (Crisp & Cook, 2013). Speciation in Allocasuarina appears to have accelerated about 25 Ma dominating the expanding temperate sclerophyllous floras of the SouthWest and southeastern Australia (Crisp et al., 2004).

The greatest rates of speciation occurred during the long Miocene Epoch (Fig. 1.1), as the climate became drier and more seasonal. Rates of trait proliferation were highest in both directions at that time. For example, the rates of evolution of species with serotiny and non-serotiny, retention and shedding of dead florets and leaves, and clonality and non-clonality among the genus Banksia were greatest then (He et al., 2011). This indicates that a great range of habitats and climate extremes was present at that time and that the Miocene was an important period in the evolution of the SouthWest flora (and Australia generally). The only exception among banksias was the thickening of the mantle of dead florets that finally covered the fruits that peaked in the Pliocene (2−5 Ma), either as a response to increasing reliance on fire to melt the resin sealing the fruits or to improve crypsis from the increasing presence of granivorous black cockatoos (C...