![]()

1

Heroic Masculinity and Its Pitfalls

Introduction: Cowboys and superheroes versus 9/11

As I described in the Introduction, according to Susan Faludi, two main archetypes of masculinity were widely invoked by the American media in the aftermath of 9/11 in relation to the men who had helped (or were believed to have helped) deal with the disaster: the superhero and the Western hero (Faludi 2008, esp. pp. 4–5, and Chapter 2). Her argument is supported by several other commentators, who discuss the use of these archetypes and the imagery associated with them in a variety of journalistic works, documentaries and other miscellaneous cultural artefacts (e.g. Mead (2010), Hassler-Forrest (2011b)).

As Ryan Malphurs observes, there are a number of basic similarities between the mythic cowboy figure and the superhero: ‘The cowboy’s character and actions are more akin to superhuman figures as he arrives on the narrative scene from vague origins with pure motives and extraordinary powers to save the community he has been called to rescue’ (2008, p. 187). Of course, this is a hyperbolic and generalized statement; few fictional Western heroes, or indeed superheroes, actually conform to such a clear-cut description. Nevertheless, it seems to me that Malphurs’s observation captures the clichéd image of these figures routinely invoked in the American cultural imagination following 9/11. The aim of this chapter is to ascertain to what extent this kind of image, and the discourses of masculinity underlying it, is reproduced in apocalyptic television series that appeared after the disaster.

While superheroes are often to be found attempting to prevent the end of the world, cowboys are not such obvious inhabitants of apocalyptic settings. Yet, as Steve Neale notes, ‘frontier mythology is by no means confined to westerns’ (2000, p. 136). Thus, while Westerns, in the strict sense of being set in the nineteenth-century American West, have been rare on television since the turn of the millennium (I have counted around five, of which Deadwood (2004–2006) and Hell on Wheels (2011–2016) are probably the most well known), there have been several series with an apocalyptic theme or post-apocalyptic setting that borrow elements from the Western genre. These include Jericho, Supernatural, Firefly, Falling Skies and TWD. I have chosen TWD as a case study because, while it is an enormously popular show – the season five premiere garnered a record-breaking 17.3 million viewers (Patten 2014) – it has also attracted widespread criticism for its depiction of gender roles, especially during its early seasons.1 It is worth reiterating here that TWD is still running at my time of writing, so its representation of gender, like all aspects of its characterization and narrative, is in an ongoing state of flux. There has certainly been some development in this regard in recent seasons, and there will doubtless be further developments in future ones. Nonetheless, as we shall see, certain themes and tropes persist or recur at regular intervals.

The presence of superheroes in recent American television has been more blatant than that of cowboys. Many live-action shows aimed at teenagers or adults that focus on them have appeared since the beginning of the century, including Smallville (2001–2011), Arrow (2012–), The Flash (2014–), Supergirl (2015–), Inhumans (2017) and Heroes, to name just a few. The latter will be my focus here because it is the only one which comes within the remit of this book in that it premiered between September 2002 and August 2012 and features an impending apocalypse—actually more than one. It also, as we shall see, draws numerous narrative and iconographic links between these apocalypses and the events and aftermath of 9/11.

The series mentioned above form part of a wider prevalence and popularity of superhero narratives in early twenty-first-century American culture, which extends to the cinema as well. As Gray and Kaklamanidou note, more than thirty Hollywood superhero films were released between 2000 and 2010, three of which entered the top-five list of highest opening weekend grosses in film history (2011b, p. 1). Some critics, including Gray and Kaklamanidou, relate this trend directly to 9/11, positing that it is responding to a public ‘need for superheroes’ (2011a, p. vi). However, others give such assumptions short shrift, notably David Bordwell, who is always sceptical of what he calls ‘zeitgeist readings’ (2008) of popular film. While Bordwell does not deny that Hollywood films may refer to contemporary events, or even on occasion carry a particular ‘message’ relating to them, he argues that it is far more common for ‘filmmakers [to] pluck out bits of cultural flotsam opportunistically, stirring it all together and offering it up to see if we like the taste’ (ibid.). If the result is not ideologically coherent then so much the better: ‘Hollywood movies are usually strategically ambiguous about politics’ (ibid. original emphasis); they are open to a variety of interpretations in order to appeal to the widest possible audience. Nevertheless, even if we accept Bordwell’s argument, this does not, as Dan Hassler-Forest points out, prevent us from viewing popular films (and television programmes) as ‘vehicles for metaphorical representations of contemporary conflicts and debates’ (2011b, p. 135). From this point of view, the texts are interesting because of the contradictory nature of the discourses they embody and their consequent capacity to engender ‘political battles of reading’ (Evans cited in Brooker 2011, p. 147).

An alternative way of looking at the revival of particular genres in times of crisis is to see them as expressions of long-standing national myths. ‘The sources of myth-making’, Richard Slotkin explains in the introduction to the final volume of his comprehensive history of the American ‘Frontier Myth’, ‘lie in our capacity to … interpret a new and surprising experience or phenomenon by noting its resemblance to some remembered thing or happening’ (1998, p. 6). This is certainly the way in which several critics, including Faludi, interpreted the prevalence of Western imagery in American media, culture and political rhetoric during the turbulent early years of the twenty-first century. For example, Liz Powell writes, ‘It is perhaps unsurprising that this genre … should be employed at a time of intense national crisis; the familiar heroic characters and themes of victory and triumph typical of the western provided traumatized citizens with a means to make sense of, and find comfort in, the aftermath of 9/11’ (2011, p. 164).

Powell’s statement could be accused of patronizing generalization in that it makes sweeping assumptions about both Westerns (e.g. that the characters necessarily behave in a ‘heroic’ manner) and viewers’ reactions to them (not only that they will find Westerns comforting but that they will identify with the ‘familiar heroic characters’). Indeed, Slotkin cautions against ‘underemphasizing the complex and various ways in which different audiences receive the production of the culture industries’ (1998, p. 10). Furthermore, he makes the crucial point that ‘no myth/ideological system … is proof against all historical contingencies’ (ibid., p. 6). Sometimes particularly shocking events or fundamental social changes occur which ‘cannot be fully explained or controlled by invoking the received wisdom embodied in myth’ (ibid.). The result is that myths, as they are expressed in popular culture, gradually alter over time, ‘blending old formulas with new ideas or concerns’ (ibid.). Thus, they should not be viewed as ‘inflexibly prescriptive. Rather they are the practical result of a continuous process of revision, and they permit a range of interpretation[s]’ (ibid., p. 351). The Western genre, Slotkin argues, is an ‘attractive’ ‘mythic space … precisely because a wide range of beliefs and agendas can be entertained there’ (ibid.). Once again, we are encouraged to view popular cultural texts as polysemic entities with a complex, not necessarily internally coherent, relationship to contemporary sociopolitical events. The wisdom of adopting such a perspective will, I think, be proven during the following close analysis of my two case studies.

The Good, the Bad and The Walking Dead

That Western heroes and their associated generic trappings are often to be found in post-apocalyptic settings is a common observation (e.g. Strick (1985), Broderick (1993a), Combs (1993), Mitchell (2001), Rees (2012)) and a phenomenon that can be traced back at least as far as the original Mad Max trilogy and its many imitators. A major reason for the existence and recurrence of this generic hybrid is surely that the Western and the post-apocalyptic text share the same basic ‘formula’. The structuralist paradigm that ‘the Western is set on the frontier at a time when the forces of social order and anarchy are still in tension’ (Pye 1996a, p. 10) equally applies to the post-apocalyptic film or programme, except that in the latter social order and anarchy are once again in tension. Society is breaking down rather than being built up, or sometimes being built up again following an earlier breakdown. Typical similarities between the two genres include both semantic elements (such as desert settings, ‘savage’ antagonists and small, embattled communities) and syntactic ones (a dialectic between civilization and wilderness, a tendency towards moral absolutism and other Manichean dichotomies such as that between the sexes).

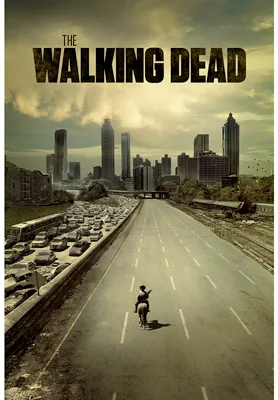

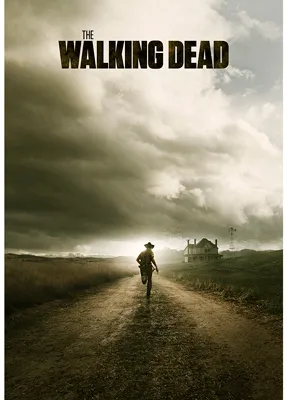

As the promotional image shown in Figure 1.1 makes clear, TWD vaunts its relationship with the Western quite explicitly. Indeed, panoramic views of desolate landscapes and/or hero Rick Grimes wearing his sheriff’s deputy’s uniform or other cowboy-style attire, usually brandishing a gun, are used to advertise the show far more often than images that give any indication of its other, ostensibly more important, generic affiliation, the zombie film. (Figure 1.2 is another example.)

Figure 1.1 TWD official season one key art. Courtesy of AMC Network Entertainment LLC.

Figure 1.2 TWD official season two key art. Courtesy of AMC Network Entertainment LLC.

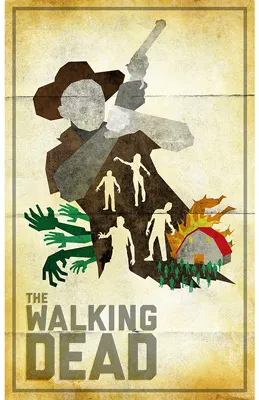

Images like these are doubtless designed to showcase the programme’s high production values and filmic visual style, which also recalls Westerns in its frequent use of wide, high-angle shots. Indeed, in an interview, Andrew Lincoln, who plays Rick, said of the cast and crew, ‘We’ve always seen Western elements’, pointing in particular to the influence of one of the series’ regular directors, Ernest Dickerson, who, according to Lincoln, ‘has a big love of the John Ford Westerns and certain shot types – the low-slung, three-quarter hip, big-sky Western shots’ (citied in McCabe 2014, p. 57). And this aspect of the show’s generic heritage has evidently been noted by at least some of its audience, as the fan-made poster (Figure 1.3) and T-shirt design (Figure 1.4) below indicate.2

Figure 1.3 TWD fan art based on a poster for the Spaghetti Western Death Rides a Horse (Giulio Petroni, 1967). Courtesy of the artist: Jason Kauzlarich.

Figure 1.4 ‘The Western Dead’, an unofficial TWD T-shirt design based on a poster for the Spaghetti Western The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (Sergio Leone, 1966). Courtesy of the artist: Dan Radcliffe, aka spacemonkeydr.

Rejecting the female sphere

One of the key functions of the Western is, as Robert Murray Davis puts it, to ‘examine what it means to be a man and how one arrives at that point’ (1992, p. xxi). Jane Tompkins goes as far as to suggest that the genre ‘doesn’t have anything to do with the West as such … It is about men’s fear of losing their mastery, and hence their identity, both of which the Western tirelessly reinvents’ (1992, p. 45). The way that it does this, she suggests, is to place its male hero in a location or situation (typically the West) ‘where the harsh conditions of life force his manhood into being’ (ibid., p. 49). Tompkins’s position is somewhat controversial; for instance, Douglas Pye maintains that her desire to ‘make the Western monolithically about gender pushes a brilliant argument to a polemical extreme’ (1996a, p. 12). However, an apocalypse, by definition, creates the harshest conditions imaginable for those who survive it; hence numerous critics have suggested that post-apocalyptic settings may have a similar appeal to that proposed by Tompkins (e.g. Broderick (1993b), Nilges (2010), Glasgow (2012), Sartain (2013), Gurr (2015)).

Adryan Glasgow’s article on this theme is about TWD specifically and she opens with a quote from the back cover of the graphic novels on which the series is based: ‘The world of commerce and frivolous necessity has been replaced by a world of survival and responsibility’ (cited in Glasgow 2012). She comments on it as follows: ‘This zombie narrative is about the competition among possible masculinities in a state of nature. The apocalypse is a playground for (blue-collar, white) men’s fantasies of masculinity in its most authentic form (read “survival” + “responsibility”)’ (Glasgow 2012). Many other critics, bloggers and online forum contributors join Glasgow in condemning the fact that TWD portrays a post-apocalyptic world in which (white) men automatically take charge (see, e.g., Donald (2011), Kearns (2012), Collins (2013)). In the early seasons especially, men make all the important decisions and are, as A. Lynn points out, ‘the gatekeepers of all the important knowledge’ (2011) relating to defence and survival. The women, meanwhile, take responsibility for domestic tasks such as cooking and laundry. While, as Lavin and Lowe point out, in later seasons, gender roles become, in some ways, more flexible, with ‘a proliferation of women in combat’ (2015, Section Five: Intersections), men continue to dominate leadership positions. As we shall see, when women do take charge, their authority is presented as fragile, flawed and temporary.

Tompkins believes that the Western, a genre preoccupied with ‘the importance of manhood as an ideal’ (1992, p. 17), came into being as a reaction against the ‘cult of domesticity that dominated American Victorian culture’ (ibid., p. 39). It seeks to repudiate ‘the discourse of Christian domesticity – of Jesus, the Bible, salvation, the heart, the home’ (ibid., p. 42) and consequently ‘to marginalize and suppress the figure who stood for those ideals’: the woman (1992, p. 39). Tompkins goes on to argue that the genre tends to reject or devalue things associated with the ‘female’ sphere, including ‘language, … religion, and culture’ (ibid., p. 55). This is, of course, a huge generalization about a genre encompassing thousands of books, films and TV series, but it is nevertheless a tendency to be found in TWD.

The very first conversation heard in the show, between Rick and his friend and partner Shane Walsh (Jon Bernthal), concerns gender difference, thereby establishing that this will be an important theme. It opens with the latter’s question, ‘What’s the difference between men and women?’ and develops into a discussion of their respective complaints about the women in their lives (‘Days Gone Bye’, 1.1).3 Shane tells tales of petty domestic squabbling with numerous girlfriends over what he believes is an innate female inability to switch off lights, while Rick feels that his wife Lori (Sarah Wayne Callies) is ‘pissed at me all the time and I don’t know why’. Supporting Tompkins’s claim that ‘Westerns distrust language’ (1992, p. 49), both men specifically complain about women’s use of it against them. Shane refers to being told, in ‘the Exorcist voice’, that ‘[y]ou sound just like my damn father’, while the more serious Rick confides that Lori continuously goads him to ‘speak, speak’ but that ‘[e]verything [he] say[s] makes her impatient’.

This conversation takes place shortly before a virus turns the majority of the population into zombies (referred to by the central group as ‘Walkers’). One of its main functions seems to be, therefore, to establish the nature of the world, and implicitly of the ‘problem’ (men’s oppression by domesticity and particularly by women and their words), which the apocalypse is about to overturn. Of course, whether or not we, the audience, are meant to sympathize with Rick and Shane’s point of view is another question. In the case of Shane, who (jokingly) refers to women in this conversation as ‘pair[s] of boobs’ and ‘bitch[es]’, certainly not, but in Rick’s, who seems genuinely hurt by his wife’s comments (and amusedly incredulous at Shane’s overtly sexist ones), maybe so.

Initially at least, the post-apocalyptic world is indeed, as Glasgow suggests, portrayed as a ‘playground’ for Shane, the archetypal macho, white, blue-collar man. With Rick missing, believed dead, he is able to assume a patriarchal position not only at the head of a group of survivors but in Rick’s family, becoming lover to Lori (tellingly, given the conversation described a...