![]()

CREOLIZATION AND CONTRABAND

Curaçao in the Early Modern Atlantic World

LINDA M. RUPERT

![]()

CONTENTS

Acknowledgments

Introduction

PART I Emergence of an Entrepôt

1 Converging Currents

2 Atlantic Diasporas

3 “Cruising to the Most Advantageous Places”

PART II Sociocultural Interactions in a Maritime Trade Economy

4 A Caribbean Port City

5 Curaçao and Tierra Firme

6 Language and Creolization

Conclusions

Notes

Bibliography

Index

![]()

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Substantial funding for this project was provided by the American Association of University Women, the American Council of Learned Societies, the Coordinating Council for Women in History, the J. William Fulbright Foundation, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Social Science Research Council, and the University of North Carolina Greensboro (UNCG). I also received assistance from the American Historical Association, the Center for Jewish Studies (University of California Los Angeles), Harvard University’s International Seminar on the History of the Atlantic World, and the Scaliger Institute at Leiden University (the Netherlands). A variety of entities at Duke University provided research support for the earliest stages. At different times I found a congenial intellectual home as a fellow at the KITLV Institute (Leiden University, the Netherlands), the Scaliger Institute (Leiden University) and at Duke University’s John Hope Franklin Institute for Interdisciplinary Studies. My analysis has been honed by discussion with colleagues affiliated with the Forum on European Expansion and Global Interaction (FEEGI), the Triangle Early American History Seminar, the Dutch Atlantic Connections working group in the Netherlands, my mentors at Duke, and my colleagues in the History Department at UNCG. The many people who have shaped my intellectual development and provided personal support over the years are too numerous to list. I am most grateful to them all. I deeply appreciate the professionalism and patience of Derek Krissoff and the entire team at the University of Georgia Press. Many thanks to Phil Morgan and Wim Klooster for their incisive comments on the manuscript. I regret that I have not been able to incorporate all their suggestions. Research would not have been possible without the tireless efforts of the archivists and librarians at all the collections listed in the bibliography. Several graduate research assistants did yeomen’s duty with a slew of tasks to prepare the manuscript for publication. Richenel Ansano deserves special mention for his support over many years. My daughters, Naomi and Aisha, grew up with this project as an unwanted third sibling. It is a pleasure and a relief to see them and the book reach maturity.

![]()

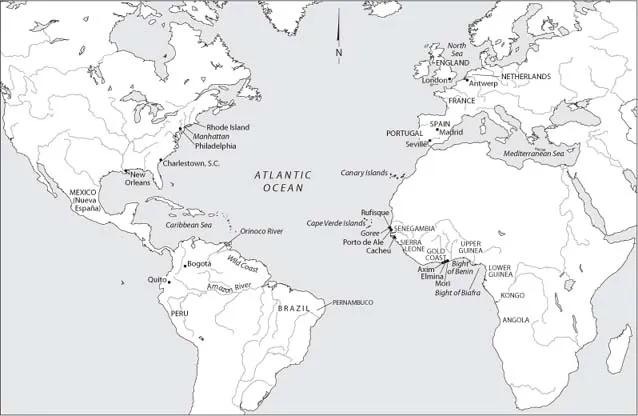

MAP 1. The Atlantic World.

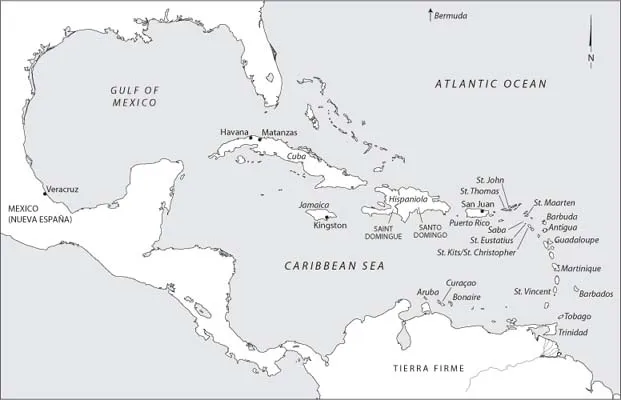

MAP 2. The Caribbean.

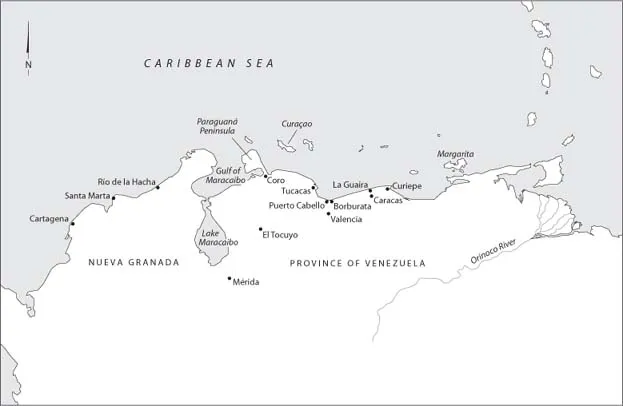

MAP 3. Venezuela and the Coast of Caracas.

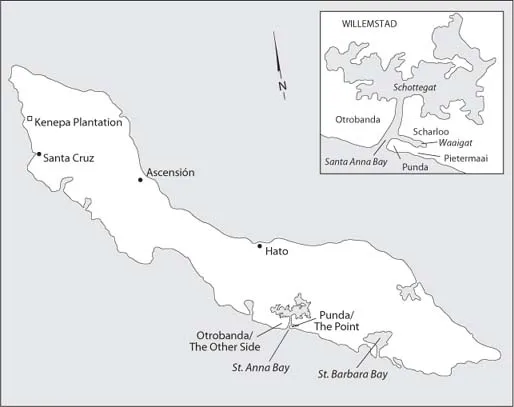

MAP 4. Curaçao.

![]() CREOLIZATION AND CONTRABAND

CREOLIZATION AND CONTRABAND![]()

Introduction

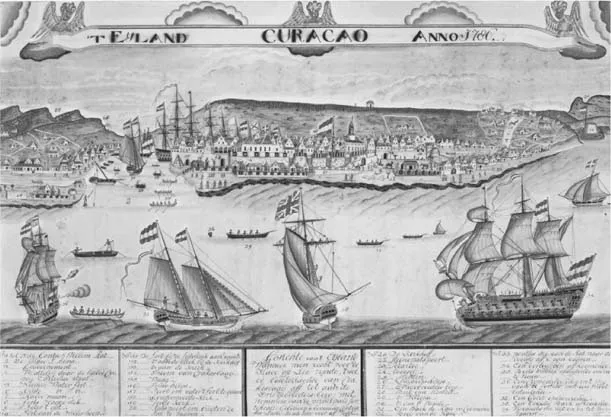

A 1786 townscape shows the bustling port of Willemstad, located on the small island of Curaçao in the southern Caribbean.1 Several full-masted ocean-going ships stand in and just outside the harbor. A dozen Dutch flags fly from these vessels and from official buildings. In the center of the drawing, securely ensconced behind the walls and protected by an imposing row of cannon, is Fort Amsterdam, seat of the Dutch West India Company. Surrounding the fort is the town, which, over the previous hundred years, had grown from a tiny outpost to become a thriving regional trade center. The West India Company (WIC), which governed the island and also dominated its trade, had been founded 165 years before, in 1621. At that time, the Caribbean was still largely a Spanish sea, but emerging European powers were beginning to gain sufficient power to challenge Spain’s territorial dominance of the region. The company’s first charter, issued by the Dutch States General on 3 June 1621, is one of the earliest articulations of the Atlantic world as a cohesive entity, centered on networks of trade that stretched from Europe to Africa to the Americas. The charter granted exclusive trading rights to the company for an initial period of twenty-four years, “to sail to, navigate, or frequent” an area that encompassed “the coast and countries of Africa from the Tropic of Cancer to the Cape of Good Hope,” and America and the West Indies, “beginning at the fourth end of Terra Nova, by the straits and passages situated thereabouts to the strait of Anien, as well on the north sea as the south sea.”2

FIGURE 1. This 1786 townscape portrays Willemstad as a bustling Caribbean port, powered by both the Dutch empire and the working majority of African descent. (© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, UK)

Thirteen years after founding the WIC, in 1634, the Dutch seized Curaçao, a small, arid island located just off the northern coast of South America. Although initially the island served as a naval base, over the decades it became a regional trade center. After the first WIC went bankrupt and was replaced by a second incarnation in 1675, the Dutch opened the island to free trade. This move was highly unusual for the times. Thenceforth Curaçao, once a backwater in the Spanish empire, was transformed into a major Caribbean commercial center, and a hub in the Dutch Atlantic system. Although the intercolonial trade conducted from Curaçao was perfectly legal under the Dutch system, much of it contravened the laws of the other European powers that had established colonies in the region. Thus, it is usually described in the non-Dutch sources as smuggling, illicit trade, or contraband.3 This vigorous maritime commerce dominated the island’s economy. It was conducted via the port of Willemstad, which was transformed from a small naval base into a cosmopolitan maritime center.

Behind the Dutch flags, the transoceanic ships, and the imposing fort, Willemstad was much more than the regional seat of a European power. The town was also a dynamic Caribbean port city. Close examination of the 1786 townscape reveals dozens of workers on the docks, lightermen rowing small boats in the harbor between the larger vessels, and fishermen. The majority of these harbor workers were of African descent. On the left side of the townscape, west across the bay, stretches another part of the port. The legend identifies it as Oversijde, literally the “other side” of town. By the end of the eighteenth century locals were calling the area Otrobanda, using the island’s developing creole language, Papiamentu.4 No Dutch flags fly over Otrobanda, nor are its impressive buildings confined behind a wall. Here, the population was more varied and multiethnic. By the eighteenth century, Otrobanda was home to a vibrant enclave of free blacks and urban slaves who lived apart from their masters and earned wages in the maritime economy.

This book traces the changing configurations of Curaçao—or Kòrsou, as it is known in Papiamentu—during the time the island was governed by the West India Company (1634–1791). Throughout this period, intercolonial commerce was not only the bedrock of the island economy, it also shaped local society. This trade provided especially rich opportunities for sociocultural interactions across established lines of race/ ethnicity, social class, and even empire. Along with the well-established European merchants who were affiliated with the WIC, Curaçao’s non-Dutch inhabitants, who constituted the majority of the population, also participated in the extensive regional trade that made the island a prosperous Caribbean hub. Women and men from two Atlantic diaspora groups in particular, Sephardic Jews and people of African descent, sustained the port city of Willemstad. They also forged close ties with communities around the Caribbean, especially with the nearby Spanish America mainland, known then as Tierra Firme (an area encompassing present-day Venezuela and parts of Colombia), and particularly with the province of Venezuela. (Contemporaries also called the Caribbean coastline of this area the Coast of Caracas.)

Creolization and contraband are the two themes that unify this book. The interplay of these two processes molded Curaçao’s emerging colonial society, I argue. These extra-official exchanges were not unique to Curaçao. Nor were they marginal. Each was prevalent in colonial societies throughout the early modern world, wherever expanding European empires thrust different peoples together and sought...