![]()

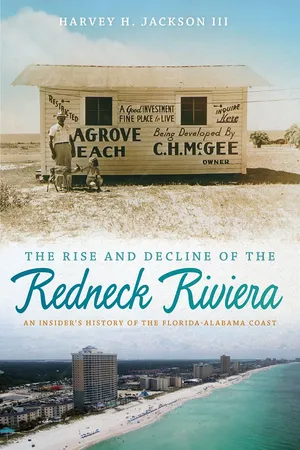

THE RISE AND DECLINE OF THE Redneck Riviera

An Insider’s History of the Florida-Alabama Coast

HARVEY H. JACKSON III

![]()

Contents

INTRODUCTION Alabama Dreaming

ONE The Coast Jack Rivers Knew

TWO The War and after It

THREE Bring ’em Down, Keep ’em Happy, and Keep ’em Spending

FOUR Times They Were A-Changing

FIVE The Redneck Riviera Rises

SIX A Storm Named Frederic

SEVEN Sorting Out after the Storm

EIGHT Playing by Different Rules

NINE Storms and Sand, BOBOS and Snowbirds

TEN Trouble in Paradise

ELEVEN Taming the Redneck Riviera

TWELVE Making Money “Going Wild”

THIRTEEN Selling the Redneck Riviera

FOURTEEN “Where Nature Did Its Best”

FIFTEEN Stumbling into the Future

SIXTEEN Who Wants a Beach That Is Oily?

SEVENTEEN The Last Summer

Acknowledgments

Essay on Sources

Index

![]()

THE RISE AND DECLINE OF THE REDNECK RIVIERA

![]()

INTRODUCTION

Alabama Dreaming

IN SEPTEMBER 1944, on the island of Oahu, half a world away from his south Alabama home, a lonely Corporal Jewel Rivers, “Jack” to his friends, wrote his wife and infant son of the wonders he had seen—the coast, an active volcano, and Honolulu, which he described as “quite a town.” His journey had been a long one; it would be longer still. “This is only a stepping stone to where I am going,” he told them. The war with Japan had brought him this far, and it would take him the rest of the way.

While his mind was on what came next, it was also on what would be waiting in the States when the fighting was over. He had seen Waikiki Beach, with its curving stretch of sand dominated by the famous Royal Hawaiian Hotel and Diamond Head. Waikiki was “very pretty,” but there was somewhere else he would rather be. “I’ll take the good old Gulf Shores any old day,” he wrote. “Give me Ala., in the U.S.A., and I’ll be satisfied.”

Not long after he mailed that letter Corporal Rivers shipped out to New Guinea. Promoted to sergeant, he served as the waist gunner on a B-24 Liberator, flying with the Ninetieth Bomber Group. On November 19, his plane took off to attack a Japanese base on Mindanao Island in the Philippines.

It did not return.

Jack Rivers never saw Gulf Shores again.

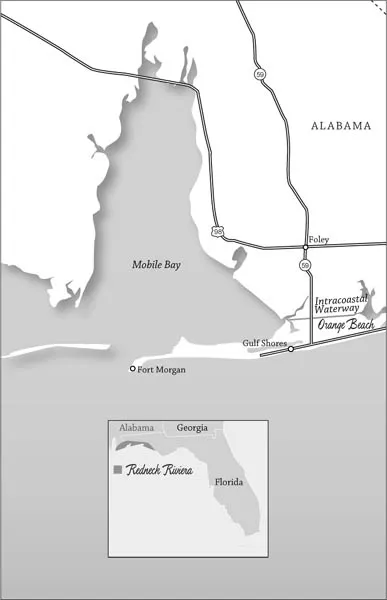

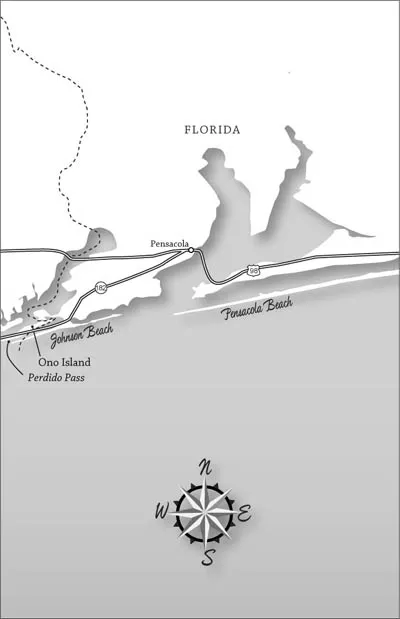

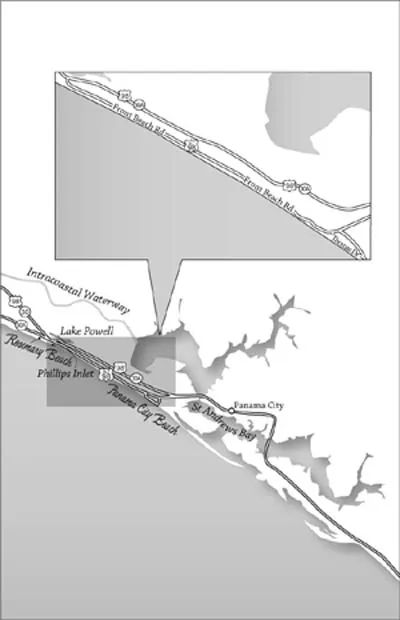

But many who served in that war did come back; and in the years that followed, veterans of the front lines and of the home front sought out sand and surf to relax and recover. Along the Alabama and Florida Gulf Coast, from the mouth of Mobile Bay east to St. Andrews Bay at Panama City, residents of the lower South made the beach their own. Children of the Depression and of conflict, more hopeful, indeed optimistic, than they had been in a decade, they drove down on New Deal–paved, military-improved roads in automobiles they bought on easy credit or with cashed-in war bonds. They came on vacations from jobs that they were trained and educated for under the gi Bill. They left behind homes financed through that same program. Few if any cared that their ticket to the middle class had been punched by the federal government.

Along this coast folks from the lower South found a way of life, a culture and context, much like the one they left back home—segregated (where blacks existed at all), small town, provincial, self-centered, and unassuming. Only the landscape was different. Few of the postwar visitors, even the ones who had served in the Mediterranean, would likely have made the connection that was made by a prewar wpa writer who saw in Gulf Shores and Orange Beach reflections of “little fishing villages that reminded the visitor of the southern coast of France.” Nor is it likely that they would have made the alliterative association that years later Howell Raines, writing for the New York Times, made when he referred to this stretch of the Alabama shoreline as the “Redneck Riviera.” From there east to Panama City Beach was, as historian Patrick Moore of the University of West Florida described it, “a provincial environment committed to tradition, conservative values, and a close tie to regional identity.”

Or that is what it has been for as long as I have known it, which is pretty much the length of time covered in this book.

Let me explain.

I grew up in south Alabama, in a little town about a three-hour drive from Gulf Shores. That beach became our beach—our Disney World, a friend from childhood called it. Though I was just a tot, I still recall going down with the family in those years after my father returned from defeating Hitler. Later I went back again and again, to deep-sea fish from Orange Beach, to dance at the Hangout, and to sleep in my car or on the sand.

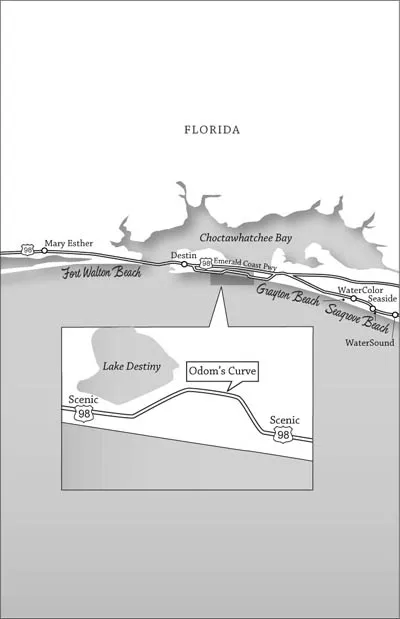

Meanwhile, even as all this was occurring, my attention was being drawn east, over to a spot in Florida, between Destin and Panama City Beach, where ancient dunes had formed a high bluff and where a developer was selling lots. In 1954 my grandmother bought one. In 1956 she built a cottage there, and from then until now Seagrove Beach, “Where Nature Did Its Best,” has been my other home.

“Bubba’s Dream”—what the Redneck Riviera was and is to so many. Cartoon by Jeff Darby; courtesy of the Mobile Press-Register.

It was there that I decided to write this book.

So here it is: my account of how people from the lower South created a coastal playground, a place where they and their families could get away from constraints and restraints of home and job and school and responsibility but without going too far—physically or culturally—from where they were. It is the story of how those who were already there, and those who came later, turned “fishing villages” and “bathing beaches” into tourist destinations for millions, places where parties were pitched, dreams were dreamed, and fortunes were made and lost. And it is the story of how people keep coming, searching for something new, something old, something upscale, and something sleazy.

What follows is how the Redneck Riviera began, what it became, and what is happening to it now. In the narrative are a number of themes that also deserve exploration and analysis on their own, and hopefully, what I have written will inspire others to have at it. In the evolution of the region one can see how efforts to build a tourist economy led to new and innovative ways to promote the Gulf Coast. However, the new and innovative ultimately altered, threatened, and even destroyed the simple, laid-back, guilt-free enjoyment of tropical indolence that attracted lower South southerners at the start. Toward the end of the story, the region is increasingly dominated not by those who want to get away but by those who want to create a coast with all the amenities and attitudes they left back home, only with sand and surf instead of suburbs and cul-de-sacs.

This is also the story of how a desire to make money off tourists forced Gulf Coast folks to reconsider their attitude toward local government and the authority, bureaucracy, and taxes that came with it. Ultimately they would give up their freedom from civic oversight in exchange for better roads, better tasting water, a dependable sewage system, fire protection, and law enforcement. Many would not like what they got in return, but the deal was made nonetheless. Woven into this are accounts of the pioneers who found ways to cater to the desires and urges of visitors and investors and in the process reshaped the land and the landscape. They turned tourist courts into condominiums and bulldozed palmetto and scrub to make way for houses and communities that some would herald as the future of urban design and others would criticize for their clawing conformity.

Then there are those who have been left behind, descendants of the first arrivals who came to the coast for the simplicity, watched as it changed, and didn’t like the result. The “no growth” attitudes of residents who “have theirs and don’t want to share it” would run headlong into the policies of those who consider the coast a commodity to package for consumers, developers who want to tame it, homogenize it, and make it palatable to people who are not rednecks or at least do not consider themselves so. All of this has been played out in rituals that, like the coast, have become increasingly commercialized—Spring Break, Fourth of July parades, and a host of “festivals” that celebrate everything from the bounty of the Gulf to Beaujolais.

At times along the way, this rush to capitalize on the opportunities the beach offers has been influenced, redirected, and sometimes stopped dead in its tracks by economic factors taking shape far from the coast. Burps and bubbles in national and international finance have been felt along the Riviera as developers and speculators have gotten rich and gone broke as a result of policies crafted in Washington and on Wall Street. And as if it were not enough that the fate of the coastal economy rests on decisions made by financiers in suits instead of locals in shorts and T-shirts, increasing concern for the fate of coastal creatures and their habitats has come in conflict with the belief, deeply held by many at the beach, that the coast is there for humans to exploit and enjoy and that what happens to a mouse or a turtle is small stuff in the bigger scheme of things.

But at the end of this story, mice and men, turtles and tourists, rednecks and real estate tycoons have found themselves facing the same situation. When the BP/Deepwater Horizon well blew and oil spewed into the Gulf, everything that walked, crawled, swam, or soared became threatened. Optimism, already dampened by recession, disappeared. As the extent of the disaster became known, a few people along the Redneck Riviera began to wonder if the compromises made to find the petroleum that fueled the cars and planes that brought people to the motels and condos were worth the danger offshore drilling posed to their way of life. However, most, in true coastal fashion, avoided alternatives that might involve sacrifice and restraint. Instead they began to press the governments they so often held in contempt—local, state, and federal—to make a company once praised as a fine example of free-market capitalism clean up the mess and reimburse coastal interests for what they lost. Though it was a time for serious soul-searching, the fact that so little of that was done may be one of the clearest indications of how attitudes that shaped the coast at the beginning of this story shape it still.

Poutin’ House South

Seagrove Beach, Florida, Summer 2011

![]()

![]()

ONE

The Coast Jack Rivers Knew

THE BEACH THAT Jack Rivers wanted to see again was not much by Waikiki standards. The same could be said for most of what would become the Redneck Riviera. Down on the Alabama coast there was no Royal Hawaiian, but there was the Orange Beach Hotel, which opened in 1923 and offered guests comfortable rooms with Delco System electrical lights and running water but no indoor toilets. The building took a beating in 1926, when the unnamed hurricane that did so much damage in the Miami area entered the Gulf, turned north, and made landfall again near the mouth of Mobile Bay. But the Orange Beach Hotel survived and was modernized (plumbing and all) in the 1930s, with cottages added to accommodate the growing number of families coming down. The year after the hurricane, the Gulf Shores Hotel opened. Built from lumber salvaged from a storm-damaged Mobile Bay hostelry, it was a two-story structure with a bathhouse on the lower level and private cottages—one owned by Mrs. Dixie Bibb Graves, wife of Alabama’s governor, Bibb Graves. Vacation homes were also springing up, the first built in the 1920s by a couple of Mobile businessmen. Laid out on the mill-town, shotgun-house plan with screened sitting/sleeping porches all around, they were harbingers of things to come. By the 1930s these retreats were joined by other cottages of similar design—“a green box roofed by a green pyramid and propped on creosote poles” recalled a member of the family that built theirs “from cheap pine mill-ends and cheaper Depression labor” and named it Sand Castle.

Getting to the coast was no easy matter. Travel was routine as far as Foley, some fifteen miles inland, but from there the trip continued on a teeth-rattling, wooden, corduroy road and over a one-lane pontoon swing bridge that could be opened to let boats pass up into freshwater creeks to ride out storms or clean sea worms off their hulls. Anchored and docked in the coves and bayous behind the beach, these boats were among the many reasons visitors came down. As early as 1913, and maybe earlier, there were locals who would take tourists out through the pass to fish deep water—for seventy-five cents a day. Once beyond the breakers it was only a brief run to the “100-fathom curve,” a dramatic six-hundred-foot drop in the floor of the Gulf where red snapper, grouper, and other popular fish clustered to feed. There upcountry folks, who had only fished for catfish and crappie, could catch the big ones, and as word of this bounty spread, “fishing for hire” became the Orange Beach industry. By 1938 a booklet titled “Tour Guide to South Baldwin County” told of fishing camps “opposite the Gulf of Mexico inlet [that led] to Perdido Bay,” and of “a fleet of charter boats . . . available at most reasonable rates, with experienced fishing guides and navigators in charge.” That same year captains and crew organized as the Orange Beach Fishing Association, and off into the promotional future they sailed.

About this same time there began to appear among coastal folks an attitude that might have passed unnoticed had it not later become a defining characteristic of the people and the place. You could see it in Carl Taylor “Zeke” Martin who, after the 1926 hurricane, homesteaded acres of beach-front that the government told him he could keep only if he tilled the soil. But the soil was sand, and raising crops was not what Zeke had in mind. So he planted fig trees, which he proudly pointed out to the homestead inspector as evidence of his intention to do what the government told him he must do, only of course it wasn’t. When the federal official left, Martin let the birds eat the figs, such as they were, and settled back to enjoy life on the beach. Charter boat captain Herman Callaway was cut from the same cloth. In the 1930s, the federal government levied a tax on charter boats and yachts. Callaway refused to pay it. Revenue agents arrived and Callaway ran them off. Then down from Mobile came the president of Waterman Steam Ship Corporation, who had heard of Callaway’s defiance and wanted to tell him that his company was going to fight the tax as well. It did, it won, and the tax was repealed. Corporate giant and charter boat captain, united in a common wariness of what the federal government, or any government for that matter, might do that they didn’t want done.

However, during the same period, and not for the last time, that same federal government pumped money into the Alabama coast and made the region more than it might have been. In 1931, the U.S. Corps of Engineers began building the Alabama section of the Intracoastal Waterway, and when it was finished two years later it had turned south Baldwin County into an island—Pleasure Island, Governor James E. “Big Jim” Folsom would later christen it. The construction brought jobs and people, improved the roads, and finally gave residents of Orange Beach and Gulf Shores a dependable bridge to what had become the mainland. A ...