![]()

CHAPTER 1

Redrawing Race

Renovations of the Graphic and Narrative History of Racial Passing in Mat Johnson and Warren Pleece’s Incognegro

Martha J. Cutter

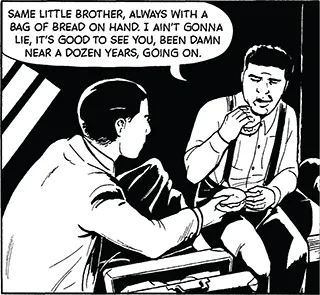

THE PUBLICATION OF MAT JOHNSON and Warren Pleece’s graphic novel Incognegro (2008) marked the first time that a graphic narrative entered and attempted to transform the vexed terrain of the literary and autobiographical passing narrative.1 Historically, the genre is fraught with questions about how race is “read,” what it means, and how unstable or stable it is: If the “black” racial passer can “pass” for white, is race only a social construction? Johnson and Pleece’s text complicates this question of the meaning of race by refusing to shade as dark the vast majority of its characters (whether they are black or white). The novel—set in the early 1930s—concerns Zane Pinchback, a reporter of African American family background who can pass for white and does so in order to collect the names of individuals who have been instrumental in lynchings in the South, writing about what he discovers under the pseudonym “Incognegro.” The novel’s plot centers on a passing mission in which Zane goes into disguise to save his brother Alonzo from lynching; Alonzo is, in theory, darker skinned and so cannot pass. Yet Zane, who sits on the left, is drawn with the same skin color as his brother Alonzo, who sits on the right (see figure 1.1). In this black-and-white graphic narrative about racial passing, then, it would seem that nothing—including physical skin color—is in fact black or white.

The illogicality of racial taxonomies in which one can look white but be coded legally or socially as black is also a crucial historical component of written passing narratives, so Johnson and Pleece’s graphic narrative complements and indeed extends innovatively many concerns of this genre. Yet the text has received little critical attention in terms of its engagement with either the historical genre of the passing narrative or, for that matter, the history of the production of race and racial passing within comics.2 Incognegro’s creators clearly are engaged in an intertextual dialogue with the rich literary and lived history of the passing genre, especially with texts published when this novel is set (in the early twentieth century); this essay investigates the graphic novel’s transformations of passing narratives from this era.3 It also situates the novel within a longer historical tradition of representations of blackness and passing in comics, within an archive of mid- to late twentieth-century cartooning. In this archive, black or passing individuals are often portrayed in a stereotyped or stereotypical mode, even when created by African American cartoonists.

Figure 1.1. Mat Johnson (writer) and Warren Pleece (illustrator), Incognegro (2008): 30.

Incognegro must therefore be understood as both a redrawing and a redressing of several types of historical texts. Through intertextuality Johnson and Pleece move from a readerly to a writerly approach to prior textual and visual historiographies of blackness and passing; in so doing, Incognegro creates something that exceeds the referents on which it is built: a writerly passing narrative—a text that the reader might consent to actively write and rewrite. Roland Barthes describes a “writerly text” as one that makes the reader “no longer a consumer, but a producer of the text” (4), describing such texts as plural, open, and infinite in the number of readings that can be produced (5). In such texts, reading becomes an activity that does not consist of stopping the signifying systems at work but of “coupling these systems . . . according to their plurality” (11); these works therefore encourage a reader to rewrite and revise them. The primary impulse of Incognegro is to open up and liberate the history of racial passing from the limited historical configurations of this genre and their encoded representation of racial subjectivity. By incorporating real historical figures into a “fictional” text about racial passing, and into their signifying network, Johnson and Pleece play with past history itself, formulating a new racial system in which we are all (black and white) potential incognegros—or unknowns—when it comes to racial identity. Furthermore, by creating a plethora of passing figures—white and black ones—who cannot be visually demarcated from “real” blacks, they also intervene in the longer history of the portrayal of race in comics, redressing this visual legacy as well.4 In finally leaving open the question of what Zane himself will be—black, white, both, or neither—and of how race itself can be visually portrayed, the authors create what Scott McCloud would call a “silent accomplice” (Understanding Comics 68) in the reader, who may also be able to hold open the historical narrative of racial passing in his or her writing and rewriting of the graphic narrative.

Historical Intertexual Referencing: Moving the Passing Narrative from a Readerly Signifying System to a Writerly One

A reader knowledgeable about the history of racial passing in the early twentieth century might experience a degree of familiarity when encountering Incognegro because the novel is filled with, and indeed boldly usurps, the plot and action of other passing narratives from this era. Of course, as Charles Hatfield notes, many alternative comics often highlight their status as a text “through embedded visual references to books, other comics, and picture-making.” Beyond emphasizing “the materiality of texts” (Hatfield 65), the creators of Incognegro have a larger purpose. Many passing narratives of the early twentieth century have a familiar trajectory: the passer decides to pass, moves to a new location, takes on a new name, and then either dies, returns to his or her “true” race, or stays outside the United States (mainly in Europe).5 There is also an insistence, frequently, that the passer has to choose one race—he or she cannot be mixed race, or on both sides of the color line, without tragic consequences. For example, a passing character in Alice Dunbar-Nelson’s “The Pearl in the Oyster” (1900) states: “we will go away somewhere where we are not known, and we will start life again, but whether we decide to be white or black, we will stick with it” (64). There are exceptions to these narrative trajectories, of course, but many passing narratives from this historical era follow them to some degree, constituting a genre unto itself—a genre that questions the meaning of race, even as it often concludes by suggesting that one must be either black or white, at least to survive in the United States during this time period. These types of denouements can be construed as readerly (rather than writerly) articulations of racial passing. Barthes argues that the readerly is based on “operations of solidarity,” on repetitions of meanings that ultimately allow them to “stick”; he notes that the ideological goal of this technique is to “naturalize meaning and thus to give credence to the reality of the story” (23). Some passing texts from this time period conclude, then, by stabilizing the plot in ways that may close down the plurality of questions the text as a whole raises about what race really is.

There are a number of intertextual references in Incognegro that refer to this narrative trajectory but also open up its history—sampling, remixing, parodying, and remaking it. For instance, Incognegro loosely follows the life of a real racial passer, Walter White (1893–1955), a very light-skinned African American who considered himself a “voluntary negro.”6 As a national staff member of the NAACP from 1918 onward and its executive secretary from 1931 to 1955, White often passed for white to investigate racial lynching in the 1920s and 1930s and was nearly lynched himself on more than one occasion when his true identity was almost discovered.7 Mat Johnson’s author’s note mentions that Incognegro is in part inspired by his learning about Walter White’s journalistic work, “posing as a white man in the deep south to investigate lynchings,” and indeed, in Incognegro Zane takes on a Walter White type of persona (4). As most readers of the passing narrative would know, Walter White was not only famous for his journalism but also for his fiction about passing, for he wrote a passing novel called Flight (1926). This novel features a female persona who boldly experiments with a white identity and business career, only to eventually and rather unconvincingly return to the “black” race, which has rejected her because of an out-of-wedlock pregnancy. Flight therefore reinserts “black” passing characters into a black social milieu; this reinsertion is unconvincing as the character was rejected due to reasons that still exist (her conception and raising of a child outside of marriage). White’s heroine, Mimi Dauphin, also sees herself as “‘Free! Free! Free!’” when she rejoins the black race, configured as “her own people” and her “happiness” (300), but there is little evidence for this in the text. The text as a whole does show the color line to be incoherent, yet in the end it unexpectedly redraws it, placing the heroine, who is of mixed-race Creole background, on the colored side. As we will see, Incognegro, which is set in a similar time period, keeps open the possibility of multiple racial alliances and identities in its ending.

Incognegro also samples features of White’s writings that are more writerly, in Barthes’s terms. White also wrote his own autobiography, A Man Called White: The Autobiography of Walter White (1948), which by title, of course, plays with the fact that a man “called white” is not really “white,” at least by the codes of this time period and by his own self-identification. Interestingly, at the end of this volume, White articulates his multiracial heritage: “I am white and I am black, and know there is no difference. Each casts a shadow, and all shadows are dark” (366). Shadows play a significant role in the obscuring of race in Incognegro, as Tim Caron has pointed out, rendering some characters who seem to be black in shadow so that a reader cannot discern their skin color, even in bright sunlight (195). Both White and Johnson/Pleece play with the racist terminology of blacks as shades or shadows, of course. Yet in the novel as a whole, Johnson and Pleece displace the rather shallow notion of race as stable that we see in a character such as Mimi with a more Walter White–like and open idea of race as mutable and unstable. Shadows, after all, are ineffable, and we all (black and white) cast them.

Moreover, at the conclusion of Incognegro the central character does not decide to be one race; instead he chooses to have several racial identities at once. In response to his brother’s question, “So what Negro you going to be, then?” the main character, Zane, responds, “That’s the best thing: identity is open-ended. Why have just one?” (129). Zane also implies that he will still “keep going incognegro. Somebody has to. I can”—that is, he will still pass for white—but he will also have an arts column “in [his] own name” (130). He will be both Zane Pinchback, a black writer in the New Negro movement; Incognegro; and perhaps other selves. Through these mechanisms, the novel illustrates that race does not exist as a coherent visual or psychological identity, as Zane states earlier: “That’s one thing that most of us know that most white folks don’t. That race doesn’t really exist. Culture? Ethnicity? Sure. Class too. But race is just a bunch of rules meant to keep us on the bottom. Race is a strategy. The rest is just people acting. Playing roles” (19, emphasis in original). In scenes such as this, Incognegro rewrites the readerly quality of the ending of some early twentieth-century passing narratives by sampling them and then producing something new—a passing narrative set in the same time period in which the passer refuses to be fixed into one identity. At the text’s end, then, the reader is asked to keep open the multiple possibilities of racial identity that the passing plot raises, to create a writerly conclusion that does not immobilize the open textual universe the graphic narrative attempts to create. Some versions of the text are subtitled “a graphic mystery,” and indeed the real mystery of the text may not be who killed whom but what race is. This particular mystery is never clarified but kept open through Zane’s refusal to pick just one racial persona.

Incognegro likewise directly references and samples a passing novel by the author, journalist, and social commentator George Schuyler (1895–1977), integrating the author’s own name: “George Schuyler, the columnist from the Messenger, even he’s got a novel coming out” (13). This satirical novel—Black No More (1931)— tells of a process wherein black characters are lightened to whiteness by a special scientific procedure. This procedure results in racial and social chaos until it is revealed that the “New Caucasians” are in fact “whiter than white”; in theory they therefore can be distinguished from the “true” Caucasians by their too-pale skin. This upends the hegemonic binary in which white skin is valued over black skin, yet it also leads to an outpouring of products and practices intended to transform skin that is too light to skin that is dark enough to be truly white (or Caucasian). The satire is clear; however, the novel also makes the point that in the United States race is still very real, and the color line is constantly being drawn and redrawn in an anxious effort to fix it, with dangerous results. At the end of Black No More a mob lynches a white Ku Klux Klan character because they have learned that he has the proverbial “one drop” of black blood. The ending of Incognegro mirrors the ending of Black No More in that the “black” character who has been passing for “white” manages to have a kkk grand wizard marked out for lynching in his stead. Yet, as Theresa Fine has pointed out, readers never see this actual lynching, as they see several others in the text, so the Klansman’s fate is put into the hands of the reader (119). This is another aspect of the graphic novel’s writerly ending, for it is up to us to decide whether we will imaginatively deliver the final blow, whether we will (in our minds) lynch the kkk man or set him free.

Another aspect of the graphic novel’s rewriting of the ending of Black No More is that the kkk man in Schuyler’s text is discovered to have the proverbial “one drop” of black blood that makes him black. Conversely, the Klans...