![]()

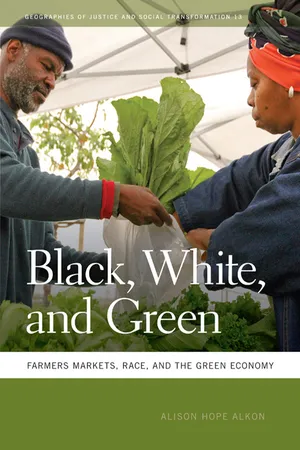

Black, White, and Green

FARMERS MARKETS, RACE, AND THE GREEN ECONOMY

ALISON HOPE ALKON

![]()

CONTENTS

List of Illustrations

Preface

1. Going Green, Growing Green

2. Understanding the Green Economy

3. The Taste of Place

4. Creating Just Sustainability

5. Who Participates in the Green Economy?

6. Greening Growth

7. Farmers Markets, Race, and the Green Economy

Epilogue. Reading, Writing, Relationship

Notes

References

Index

![]()

ILLUSTRATIONS

IMAGES

North Berkeley Farmers Market

West Oakland Farmers Market

Chez Panisse Restaurant

North Berkeley’s Edible Schoolyard

Bobby Seale surveying bags of groceries

Redlining map of Oakland and Berkeley

Slim Jenkins bar/restaurant

Seventh and Mandela on a nonmarket day

David Simpson and Chris Sollars

Customers at Riverdog Farm’s stand

Berkeley Farmers Market used-bags sign

Farm Fresh Choice logo

Farmer Michelle Scott restocking produce

Typical West Oakland corner store

Market manager David Roach spinning records

West Oakland farmer Leroy Musgrave

Farmer Will Scott sorting produce

Bertenice Garcia and husband Jose selling strawberries

Maps of Oakland by race and percentage living in poverty

A worker/owner at Mandela MarketPlace

Mother and children at North Berkeley Farmers Market

TABLES

1. Demographics of Farmers Market Neighborhoods

2. Economic Value of the Green Economy

3. Demographic Comparison of West Oakland and West Oakland Farmers Market

![]()

PREFACE

This book has been almost a decade in the making. In 2005, I moved to Oakland to try to better understand how and to what end low-income communities of color were making use of local food systems. There, I met a group of people working to connect African American farmers and small businesspeople to residents of neighborhoods that lacked healthy food choices. The experiences of this group — which includes Jason Harvey, David Roach, Dana Harvey, Leroy Musgrave, Will Scott and the Scott family, Charlotte Coleman, Ted Dixon, Xan West, and Jada White — are at the core of this book. Their efforts, and their willingness to share them with me, had a profound effect on my thinking about race, food systems, and local economic (under)development, and I am incredibly grateful to them.

But in another way this project started long before I came to Oakland. I had begun to become involved in local food system work as an AmeriCorps volunteer in Atlanta. When it came time to choose a graduate program, Davis’s vibrant alternative food scene had as much to do with my decision as the academics. I quickly connected with like-minded people through the Domes, a cooperative campus housing community that included gardens, chickens, fruit trees, and friends who would soon teach me how to live in such a place. These new friends, often well connected to the wider organic farming scene, helped me see our home as part of a larger movement for sustainable agriculture. And yet we couldn’t help but notice that this movement was overwhelmingly white.

This book started out as an attempt to answer the question “Why are we all so white?” though I recognize now that this was the wrong question. There are growing numbers of people of color developing local food systems and challenging dominant ideas about food, agriculture, and the environment in exciting ways. I shifted my questions to explore how race intersected with thinking about local and organic food systems.

This shift in my questions guided me toward a comparative project. By also studying an affluent, predominantly white, progressive farmers market, I could follow the sociological dictate to “make the familiar strange” and treat this kind of local food system as something to analyze rather than take for granted. Here, I was fortunate to get to know the managers at the North Berkeley Farmers Market, particularly Rosalie Fanshel, Linda Bohara, Herman Yee, and Max Cadji. I learned much from these individuals’ impressive dedication to both sustainability and social justice, as well as from the Ecology Center’s support for a just sustainability approach. I am also grateful to all the vendors and customers, too many to name, who shared their insights and their warmth.

Ethnographic work starts with data, and lots of it. The task then shifts to analyzing the data absent pre-established questions, figuring out what is most significant about a particular social world and what it has to say to both academics and laypeople. In this endeavor, I have been incredibly fortunate to be a part of multiple and intersecting communities of scholars. Tom Beamish shaped this work in a number of important ways, most fundamentally by suggesting that I think about farmers markets as places of economic exchange as well as social change.

Many aspects of this book were initially articulated and developed through related collaborative projects. Articles coauthored with Christie McCullen, Kari Norgaard, and Teresa Mares helped me gain a better understanding of why farmers markets and food movements are so culturally important. And the process of coediting Cultivating Food Justice (MIT Press 2011) with Julian Agyeman pushed me to sharpen my understanding of food justice as both a social movement and a body of academic work. I am also grateful to all our contributing authors, whose research has deepened this exciting and dynamic field.

During and beyond my graduate training, I have also benefited from the support of the UC Davis Environmental Justice Project (Julie Sze, Jonathan London, Marisol Cortez, Raoul Lievanos, and Tracy Perkins), the UC Multi-campus Research Group on Food and the Body (especially Julie Guthman, Melanie DuPuis, Kimberly Nettles-Barcelon, Carolyn de la Peña, and Laura-Anne Minkoff-Zern), colleagues and mentors in the UC Davis Sociology Department (Jim Cramer, Joan S. M. Meyers, Dina Biscotti, Julie Collins-Dogrul, Jen Gregson, Macky Yamaguchi, and Lori Freeman), and colleagues at the University of the Pacific (Marcia Hernandez, Ethel Nicdao, George Lewis, and Ken Albala). Thanks also to my friends, many of whom are incredibly passionate about issues of food justice and social change, especially Natalia Skolnik, Dana Perls, and my partner, Aaron Simon, as well as to my family, Penny, Michael, and Matty Alkon, for their love and good humor.

Lastly, a number of individuals at University of Georgia Press have helped me develop this manuscript into a book, and their work is strongly reflected in these pages. Particular thanks go to Nik Heynen, Derek Krissoff, and the anonymous reviewers, each of whom offered helpful suggestions. It goes without saying, however, that all errors are mine alone.

![]() Black, White, and Green

Black, White, and Green![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Going Green, Growing Green

Green is how we describe a world of social justice, healthy communities and ecological balance. Green is the color of hope.

— Green America, nonprofit manager of the Green Business Network and publisher of the National Green Pages business directory

We must insist that the coming “green wave” lift ALL boats. Those low-income communities that were locked out of the pollution-based economy must be locked into the clean and green economy.

—VAN JONES, “Forty Years Gone: MLK’s Dream Today Would Be Colored Green”

If we wait for the magic of the market to solve inner-city food problems, I fear we’ll be left hungry for change.

—TOM PHILPOTT, “Urban Farms Don’t Make Money—

So What?,” Grist

It’s Thursday afternoon, and the sun is shining. Customers stream into the North Berkeley Farmers Market from all directions.1 Some lock their bicycles to parking meters behind the vendors’ tents while others come on foot or have parked nearby. Patrons stroll from one artfully decorated booth to the next, sampling peaches in the summertime and apples in the fall. Approximately fifteen canopy-covered stalls fill a blocked-off city street, facing inward toward a grassy, tree-lined median. Beneath the farmers’ tents lies a cornucopia of fresh food. The winter crops are mostly green — spinach, lettuce, cabbage, chard, and kale — though carrots, oranges, and beets add splashes of color. Summertime is a rainbow of tomatoes, summer squash, strawberries, melons, and peppers.

Patrons strolling through the market are surrounded by snippets of casual conversation. Friends and neighbors greet one another, warmly inquiring about families and common friends. Some seem to have run across each other unexpectedly while others have planned their meetings. Many visitors, especially women and young children, sit on the grass and savor their purchases. At the various booths, customers animatedly share nutrition advice and food preparation techniques or probe farmers about their cultivation practices. Farmers seem to enjoy the social interaction. One farmer, for example, describes her pride in the compliments she receives. “People say the most incredibly generous things about your food,” she says, “like, ‘That was the best meal I’ve ever eaten,’ or ‘Thank you so much for doing this work.’ Just the joy.” She pauses for a moment before continuing. “I mean, around food is such a pure kind of wonderful joy! People are so supportive!” Other vendors, as well as managers and customers, often echo the sense of warmth and connection conveyed by this farmer, commonly describing the North Berkeley Farmers Market as sociable and relaxed, with a slower pace than other area markets and grocery stores.

Founded in 2003, North Berkeley is the most recent addition to the Berkeley Farmers Market landscape. Like its predecessors in south and downtown Berkeley, it is managed by the Ecology Center, one of the city’s veteran environmental organizations. Since 1969, the Ecology Center has run a variety of urban sustainability initiatives, including Berkeley’s curbside recycling program, the first in the country. While many farmers markets are associated with environmental themes, the Ecology Center ensures that such themes are the focal point. Its bylaws allow only organic produce from local growers, and all but one of its farmers come from within 150 miles of Berkeley.2 Prepared foods must be at least 80 percent organic, use local ingredients whenever possible, and be served on compostable plates.

The North Berkeley Farmers Market is also extremely profitable for vendors. On the rare occasion that a space becomes available, potential applicants are evaluated on environmental considerations, including organic techniques and the miles the food will travel. Proponents of this farmers market tend to view the buying and selling of local organic produce as an environmental good because it decreases dependence on the fossil fuels necessary for transport, pest and disease management, and manufactured fertilizers. Vendor Antonio Magana, who sells vegan Mexican food, describes this sentiment when he declares, “Every time you come to my stand, you’re part of the change.” This linking of sustainable products and social change is important beyond food politics. It is the cornerstone of broad efforts to address environmental and social issues through ethical consumption.

Despite the presence of Latino/as, African Americans, and Asian Americans, the North Berkeley Farmers Market is largely affluent and white. It takes place in the so-called gourmet ghetto, a striking name given that its high-end boutiques and restaurants are the antithesis of the poverty the word ghetto implies. Many of the surrounding restaurants share the farmers market’s penchant for local and organic food — within a few blocks shoppers can find products such as biodynamic wine and organic pizza with seasonal toppings. The best-known neighborhood stalwart is Alice Waters’s Chez Panisse, which was among the first restaurants to feature local and organic foods and to highlight farmers’ contributions. Chez Panisse is widely thought of as the birthplace of “California cuisine,” which fuses French-inspired tech...