![]()

1

Planned Illegalities

The Production of Housing in Delhi, 1947–2010*

The City was not planned as it is, but the City is an outcome of planning.

—Lisa Peattie (1987: 15)

In a room full of luminaries on a spring day in Delhi, the city searches, yet again, for illumination. The workshop is another of what seems like an endless number in the unfolding of the urban agenda in India across the academy, policy and government, private enterprise, as well as in the media. The ‘Urban Turn’ seems complete (Prakash 2002). On the masthead this day is the ‘21st Century Indian City’.1 The lead author of the latest urban manifesto—the High Powered Expert Committee Report on Urban Infrastructure (HPEC 2011)—is the lead panelist of the opening session of the workshop. She speaks eloquently about the need for growth in urban infrastructure and the mechanisms by which these are to be attained. At the end, almost as an afterthought, she sums up one of the reasons why her work was, in a way, ‘simple’. The committee’s approach to infrastructure provision, she says, was ‘obvious’ because, ‘planning, as we all know, has failed in Indian cities’.

The ‘failure of planning’ has become a ubiquitous and commonsensical refrain uniting voices from across sectors, disciplines and ideological positions. In 2006, the then Prime Minister Manmohan Singh inaugurated the Jawahar Lal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM)—India’s largest urban programme and policy intervention in her history—saying the cities needed to ‘re-think planning’.2 Global analysts McKinsey & Co. root India’s ‘poor state of urban planning’ in urban and regional plans that are ‘esoteric rather than practical, rarely followed and riddled with exemptions’ (McKinsey Global Institute 2010). Members of social movements representing the urban poor go further, describing and protesting what some have called the ‘total bankruptcy and arrogance of the planning process’ that has led to a ‘systemic failure of modern planning’ and deep exclusions in Indian cities (D. Roy 2004). Decades apart, Ashis Nandy (1998) and Jai Sen (1976) both famously described Indian cities as ‘unintended’.

The planners’ desire to ‘effect a controlled and orderly manipulation of change’ has been, argues Amita Baviskar, ‘continuously thwarted’ by the ‘inherent unruliness of people and places’ (2003: 92). Urban planning is considered, at best, ‘hopelessly inadequate’ in terms of being able to tackle this chaos (Patel 1997) though inadequacy is the gentlest of the charges levelled against planning. Citing the twin jaundice and cholera epidemics in Delhi in 1955 and 1988, Dunu Roy argues that the worst aspect of the failure of planning was that, in fact, ‘planners did not even understand the implications of what they themselves had done’ (D. Roy 2004).

Crisis-ridden as well as crisis-inducing, chaotic, irrelevant, incompetent, exclusionary: planning in India indeed does indeed seem to have failed. In Indian cities, this ‘failure’ has acted as a reason, impetus and justification for a range of diverse urban practices—increasing judicial intervention into urban governance by the higher courts; political action by civil society organisations and resident associations; the emergence of new forms of public-private governance mechanisms within urban reform; and policy paradigms as well as trenchant critiques by social movements seeking rights to and in the city. Narratives of ‘failure’ also critically inform the main subject of this book: the evictions of bastis3 through judicial orders in the name of public interest. In ordering evictions, the Delhi high court and the Supreme Court of India frequently used the terms ‘planning’ and ‘planned development’ with an air of familiarity, resting on the assumption that their meaning and representations were both obvious and commonly shared. As they did, in the same breath, they repeated their diagnosis that ‘planning’ and ‘planned development’ had indeed ‘failed’.4 It is here then that we must begin.

How do we assess the ‘failure of planning’? Narratives of ‘failure’ are simultaneously narratives of planning. Accusations of chaos, irrelevance, incompetence and exclusion, in other words, each rely upon an imagination of what functional, relevant, competent and inclusionary planning could and should look like within an Indian city. ‘Failure is,’ in Ravi Sundaram’s (2009) words, ‘a diagnostic of planning’. In this book, I take Sundaram seriously. I ask not if planning has indeed failed but instead frame a different inquiry: What is the work done by the idea and discourse of ‘failure’? What, in other words, does the idea of ‘failure’ itself make possible within and as planning?

In this chapter, I am interested particularly in the ways in which failure intertwines with some more familiar objects of urban theory when studying cities of the global South: informality and illegality, both of which are closely seen as the most visible manifestations of the failure of planning. I thus interrogate failure within a specific aspect of urban development: the production of housing in the city. My questions become narrower and more specific: what is the relationship between planning, the nature of its single or multiple ‘failures’, and the production of housing in the city? In particular, how does planning relate to conceptions of illegal and informal housing closely associated both with urban marginality as well as with narratives of failure? What, in other words, does planning and its ‘failures’ tell us about the ‘slum’?

I seek answers to these questions through constructing a necessarily partial but illuminating history of inhabitation in the city. Using a series of geo-spatial maps, I visualise where housing across the city’s planning categories was built from the issuance of the first master plan in 1962. On these maps, I then transpose Delhi’s three master plans, using the result along with additional housing data to assess the relationship between these master plans and the building of actually existing housing stock. I seek to map, in a sense, the magnitude and textures of the gaps between imagination, intention and actual practice—arguably one of the most commonly understood ‘failures’ of planning. Finally, I map evictions in the city from 1990 to 2007 in order to juxtapose sites of eviction, existing housing stock and the master plans to further interrogate the idea of ‘planned development’.

In doing so, I argue that, in Delhi, the ‘chaos that is urban development’ (Verma 2003) is not planned but it is, to twist Peattie’s phrase, an outcome of planning. Plans do not control but they influence, determine and limit. Problematising planning’s failures allows us to find what I am calling the traces of planning—its legacies both historical and contemporary and its presence in the contemporary city either in absence or presence, in failure or success. These traces challenge the ideas of a ‘politics of stealth’ (Benjamin 2008) as a narrative of subaltern urbanism in cities of the global South. They also reject simplistic diagnoses of ‘failure’ built upon the misrecognition of assumed distinctions between formal/informal and legal/illegal, and the association of informality and illegality as exclusive domains of the politics of the marginalised. Looking at the actual practices of settling the city, I argue, suggests instead that it is between illegalities practiced by a diverse range of urban residents where we must look to understand the urbanism that lies beneath a ‘failed’ plan. These illegalities are not ‘outside’ planning or a mark of its ‘failure’, but are produced and regulated within planning itself. I conclude by arguing that urban practitioners in a city like Delhi must, therefore, engage with planning precisely because of the continuing relevance of what are considered its ‘failures’. The terms of such engagement require new conceptual categories. I propose the idea of legitimacy, rather than legality or formality, as a more useful conceptualisation for a more relational urban politics that also more accurately reflects the history of the production of space in southern cities.

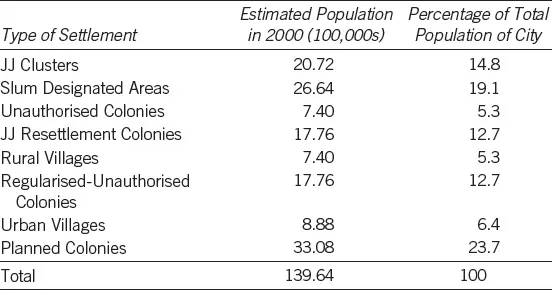

Histories and categories of inhabitation: To assess housing, I return to a table I used in the introduction. It is based on data from the chapter ‘Urban Development’ in the Economic Survey of Delhi, 2008–2009, presenting ‘description’ of ‘types of settlements’ in Delhi in order to ‘explain the situation’ in the city (Government of Delhi 2009).

As I argued earlier, this table is still the most (and indeed the only) cited set of statistics on the types and relative quantum of housing in the city, used equally by the Judiciary, planners within the DDA, the city and central governments, the municipal authorities, the media and by city residents themselves. In our assessment of planning’s failures and the particular history of those failures in Delhi within housing, the table therefore represents an ideal starting point.

Table 1.1: Settlements in Delhi

Source: Drawn based on data from statement 14.4 of Government of Delhi (2009).

At first sight, the table seems to confirm a failure of planning: What could be a greater indictment than nearly 75 per cent of the city living in housing that is apparently ‘unplanned’? Yet as we problematise this failure, we must ask a different set of questions. From the extensive and interdisciplinary literature on how to think about classification, three key elements are relevant for our purposes. I trace these below.

Thinking in Categories

The first element is that categories entail choices of what to include and what to leave out. Boundaries must be created, defined and policed for the category to have meaning and be useful. Modern statecraft, argues James Scott, works in part through such simplification—the reduction of ‘an infinite array of detail to a set of categories that will facilitate summary descriptions, comparisons and aggregation.’ These ‘forms of knowledge and manipulation’ are particularly characteristic, he says, ‘of powerful institutions with sharply defined interests’ of which state bureaucracies and institutions are emblematic (1998: 77). These categories, Scott warns, must ‘collapse or ignore distinctions that might otherwise be relevant’ (ibid.: 81).

It is not just that ‘other distinctions’ between categories are ignored, argues Amartya Sen, but that they are deemed less important and hence marginalised. Writing about social theories on inequality, Sen argues that different frameworks prioritise a different ‘primary variable’ that they use to then compare and construct categories. The need ‘for ensuring basal equality’ in the primary variable, argues Sen, then ‘necessitates the tolerance of inequality in what are seen as “outlying perspectives”’ (1992: 131).

From Sen and Scott, we get a set of questions about the construction of categories in our table: What is the ‘infinite array of detail’ that these categories reduce? What do they reduce them to? What are the ‘other distinctions’ (or similarities) that are erased? Or, in Sen’s terms, what is the primary basis of classification of settlement typologies, of separating the ‘planned’ from the ‘unplanned’? What are then the ‘outlying perspectives’ that this primary basis allows us to consider marginal or less important?

The second element is that categories are often parts of systems and processes of order and ordering. In her seminal study of ideas of pollution and dirt, Mary Douglas argues that dirt is essentially ‘disorder’—it is ‘matter out of place’ (1966: 35). What are order and disorder? Order implies ‘restriction’, says Douglas, because ‘from all possible relations a limited set has been used.’ Disorder, in contrast, ‘is unlimited, no pattern has been realized in it, but its potential for patterning is indefinite … disorder symbolizes both danger and power’ (ibid.: 94). Categories and the order they are meant to represent must then guard against what Douglas calls anomalies and ambiguities. In culture and through ritual then, ‘ideas about separating, purifying, demarcating, and punishing transgressions’ play this role, a continuous and fragile attempt ‘to impose system on an inherently untidy experience’ (ibid.: 4).

From Douglas, we get a second set of questions: What is the dirt—the ‘unplanned’—that this system of settlement typologies is trying to keep at bay? What, in other words, is the disorder? What patterns is this ‘disorder’ capable of and what ‘danger’ does it represent? How does this system of order guard against ambiguity and anomaly—what are its ‘rituals of separation, purification and punishing transgression?’

The third element we must consider is that categories are generative, not just descriptive. In other words, they create and reproduce, albeit imperfectly and incompletely, what they describe or narrate. For Scott, descriptive categories become ‘categories that organize people’s daily experience precisely because they are embedded in state-created institutions that structure that experience.’ They are the ‘authoritative tune to which most of the population must dance’ because they can be given ‘the force of law’ (1998: 83). Douglas argues that cultural categories frame experiences just as powerfully. She says that, ‘public, standardized values of a community, mediate the experience of individuals [by providing] in advance some basic categories, a positive pattern in which ideas and values are tidily ordered’ (1966: 39). It is the ‘public character’ of these categories that gives them ‘authority’, which may or may not be enshrined in law.

A third set of questions then arises: How have our housing categories been generative—how have they shaped the built form of the city as well as urban politics? In doing so, how have they impacted and managed the trajectories, subjectivities and claims of resistance to them, or deviance from them?

Built Categories and Built Environments: A History of and through Settlement Typologies in Delhi

Armed with the set of questions above, I now turn to the analysis of the categories of housing presented in Table 1.1, taking each in turn. Before that, I briefly mark two final necessary contextualisations—a clarification on terms, and a history of Delhi’s three master plans.

Legal, Formal, Planned, Legitimate: A Clarification on Terms

In the analysis that follows, I use a recognisable but often confusing vocabulary to describe settlements: legal/illegal, formal/informal and planned/unplanned. My use of these terms is strategic. I use them despite knowing their limitations and the lack of clarity in their competing definitions. I do so precisely to make these limitations visible, to highlight internalised foreclosures, and to show the political work these perform as terms used widely within legal, planning, academic as well as everyday discourse.

Specifically, I use the term ‘planned’ only when it is used by the table itself, i.e. in describing the ‘Planned Colony’. I limit my use of ‘legal’ to only refer to housing that is recognised by the Plan to the extent that the owners of the house possess some kind of recognised title or ownership that can be registered with local authorities and is recognised by the state. To describe documented transactions of sale and purchase of property or built housing whether or not the resultant titles are legally recognised, I use the term ‘formal’. To describe violations of building norms, developmental controls, and layout plans, regardless of the legality or planning status of the settlement, I again use the twin terms ‘formal/informal’. As I will argue later, this separation in terming the violations of certain norms as ‘illegal’ and others as ‘informal’ is one that emerges from the settlement typologies themselves and has significant implications for settlements and their residents alike.

I introduce one additional term to the above vocabulary: legitimate. I use legitimate to describe settlements that enjoy a de facto or de jure security of tenure. I mean by this that they are protected—either explicitly w...