eBook - ePub

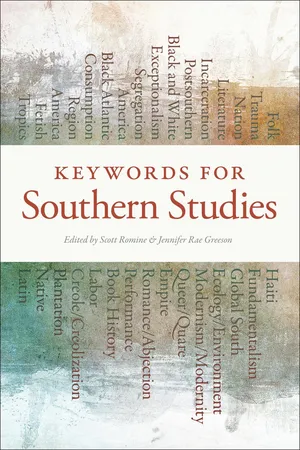

Keywords for Southern Studies

- 424 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Keywords for Southern Studies

About this book

In Keywords for Southern Studies, editors Scott Romine and Jennifer Rae Greeson have compiled an eclectic collection of new essays that address the fluidity of southern studies by adopting a transnational, interdisciplinary focus. The essays are structured around critical terms pertinent both to the field and to modern life in general.

The nonbinary, nontraditional approach of Keywords unmasks and refutes standard binary thinking—First World/Third World, self/other, for instance—that postcolonial studies revealed as a flawed rhetorical structure for analyzing empire. Instead, Keywords promotes a holistic way of thinking that begins with southern studies but extends beyond.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Publisher

University of Georgia PressYear

2016Print ISBN

9780820349626, 9780820340616eBook ISBN

9780820349619Regimes

Incarceration

There is a United States northern narrative of incarceration. It is a story highlighted by expressive traditions that foreground legacies of Puritan and Quaker spirituality. Puritans migrating to the New World envisioned themselves as architects of a “City on the Hill” that would serve as a beacon and moral compass for Old World redemption. They conceived themselves as anchoritic “sinners in the hands of an angry God,” a God who, if provoked, would launch a fierce “Quarrel with New England.” The Jeremiadic Puritan imaginary features perilous ocean voyages and vigorous holy assaults by Puritans on “savage” Native Americans. There are also holy errands into the wilderness to hear God’s voice and receive his deliverance. From the first third to the middle of the nineteenth century, such fervid theocratic visions of mission, conquest, and salvation yielded to—or perhaps more aptly, “morphed” into—secular analogues. Religion, transcendentalism, urban industrialism, and bureaucratic state apparatuses converged in new formations.

Monastic solitude transformed into Ralph Waldo Emerson’s and Henry David Thoreau’s transcendental and Walden Pond wisdom on the Over-Soul. Protestant gospels of faith and work, sin and penitence, were casuistically transformed into a carceral system that created, and then punished, social pariahs. Gallows and whipping posts were moved indoors, ending theocratic state-sanctioned spectacles of punishment in the public square. Demographics that had been civilly excluded from the republic’s founding were officially criminalized and incarcerated. The criminalized were stripped of personhood and cast into tight spaces of labor and confinement. Almshouses, orphanages, madhouses, poorhouses (as Thomas Jefferson’s Notes on the State of Virginia make clear) were all historically parts of America’s colonizing polity. But like the instrumentalities of punishment such as public whipping posts and pillories, those criminalized for “difference” such as madness or insufficiency were hauled inside. They were banished from the sight and rights of civil society. No institution was more iconic with respect to the plight of what might be called the “republican damned” than the penitentiary.

Deemed “penitents” by Quaker protocols of punishment and rehabilitation, penitentiary inmates were deprived of all human contact. Absolute solitude was the prescription from their warders. Secular solitary confinement would lead the condemned on a journey of regret, remorse, and redemption. It was assumed that the journey also required profitable penitent labor. The profit from such labor would not, however, go to the penitent but would be confiscated to enhance the coffers of the state. Pennsylvania’s—the “Quaker State’s”—legislature approved architectural plans and financing for the Eastern State Penitentiary in 1831. The penitentiary was constructed during succeeding years on eleven acres located just outside Philadelphia. Hence, what might be termed “northern, republican incarceration” was established less than a morning’s walk from Independence Hall, birthplace of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States of America.

With its symmetrical, radiating, glass-roofed cellblocks and central guard tower, Eastern State Penitentiary was a model Panopticon. The eighteenth-century philosopher Jeremy Bentham first conceived of an architectural space that featured a way of viewing all inmates from a central guardhouse or tower. The panoptically incarcerated would always be under surveillance. The first prisoner to enter Eastern State Penitentiary was a black man convicted of burglary and sentenced to two years of “confinement in solitude with labor.” Eastern State, as its name denotes, was part of the state apparatus of punishment. Its operation demanded taxonomies of belonging and exclusion that served state interests. A phenomenology of inside and outside was indispensable to its project.

The French philosopher Michel Foucault persuasively analyzes in Discipline and Punish and Madness and Civilization how the birth and effective management of the modern state demands sites of incarceration. Asylums, jails, and prisons are placeholders—negations of the civil habitus meant to separate in-mates from the sociality of life outside. Such sites are meant visibly—in the eye of the law—to differentiate the in-sane and criminal from the prudent and rational man of the law. Foucault’s wisdom might translate in the idiom of everyday life as the following hypothetical statement: “We know we are innocent, law-abiding, sane, and blessed citizens at a glance. We have only to note that we are not restricted by: narrow cells, forbidding stone walls, razor-wire barricades, psychiatric-ward invisibility, and maximum-security isolation. We are not ‘in-mates.’”

Nineteenth-century French commissioners such as Gustave de Beaumont and Alexis de Tocqueville traveled to America to observe the marvels of the northern carceral regime at Eastern State Penitentiary. English novelist Charles Dickens did the same; he left with a dim view of what discipline and punishment—U.S. northern urban style—augured for man’s humanity to man. Tocqueville pondered what “republican carcerality” portended for the fate of the penitent and the larger society. He wrote: “It is well known that most individuals on whom the criminal law inflicts punishment have been unfortunate before they become guilty.”1 Structural conditions, in short, breed insufficiency, harmful associations, and criminal behavior. Still, the complete-solitary regimen of Eastern State Penitentiary seemed calculated to drive inmates mad. Tocqueville felt that New York’s Auburn State Penitentiary (1819) offered a model of incarceration that was more conducive to rehabilitation leading to a restored citizenship. Inmates at Auburn State dined and labored in congregation, though also in silence. Its cells were tiny spaces intended principally for detention and sleeping. Like Eastern State, Auburn was a profit-accruing venture with no significant returns to the inmates who produced the profit.

Tocqueville’s sense of the structures and implications of the carceral are analogous to Foucault’s observations. Those “marked” by signs of a reputed religious condemnation (e.g., born “black” like the scriptural Ham) or burdened by economic misfortune (e.g., conceived in poverty) are the socially damned who are criminalized into incarceration. To maintain civil society and the content of its privileged rulers, staff, and administration, it is deemed necessary to create a damned caste that is “convicted in the womb.”

There is a construction and account of U.S. history that makes clear the inalienable conjunction between the Constitution of the United States of America and the proximate architectures of American incarceration. The Constitution is rife with taxonomic exclusions and anatomical chimeras (e.g., “three-fifths” of a person). It has been remarked that when Tocqueville toured the United States, the only fully franchised citizens were white men. The most privileged of that white male demographic were rich by financial account and pseudoaristocratic by self-proclamation.

Perhaps none were more “pseudo” in their aristocratic protestations and wealthy in their accounts than large plantation owners of the American South. Hence, the Constitution had to be hammered out in terms that would satisfy both a northern narrative of nationhood and the tale of an immensely wealthy and irrepressible southern sphere. That southern sphere’s immense profits derived from the labor-in-bondage that was American chattel slavery. Statesman James Madison observed that southern slavery—the incarceration of black laborers by the millions in abject plantation servitude—formed the “line of distinction” between northern and southern delegates at Independence Hall. The Constitutional Congress that convened at Independence Hall—well in advance of Tocqueville’s tour—was, not surprisingly, constituted by an all-white, male-bonding exercise in compromise and exclusion. The convention arrived at common cause not so much by a fierce commitment to liberty “for all” as through a mutual northern and southern devotion to a plutocratic autonomy and ideological cohesion predicated on racial and gender exclusion.

We know the success of the Independence Hall constitutional project from its boundless and continuing legacy. It guaranteed untold inherited wealth and privilege for countless white American generations. Madison’s “line of distinction” was, ultimately, a demarcation between the privileged white male rich and the populous and punished damned “other.” Ultimately Madison’s line was the economic bottom line of plutocratic self-interest. The final draft of the Constitution approved by the convention is marked by the delegates’ self-interested fictions and denials. Women are granted no suffrage. Native Americans are designated beyond the pale of settled civilization. Black slaves are legally fictionalized as creatures never seen: three-fifths of a man. Specifically, Articles I and IV of the Constitution and their clauses mandate the following: continuation of the African slave trade to the United States until 1808; apportionment of representation among the several states on the basis of a definition of black slaves as “three-fifths of all other persons” (three-fifths clause). There is also the “fugitive slave” provision mandating that escaped slaves must, by law, be returned to their owners.

Calculated deletion of the word “slavery” from the Constitution by the delegates in no way compromises the truth and the historically verifiable record that slavery was written into the founding legal document of the United States. The national legal “bright line” was constituted and conditioned by an order of incarceration complementary to the state apparatus of penitence and penitentiaries. Chattel slavery, through constitutional compromise, exclusion, and fiction, became a template for American incarceration. Such slavery was the very engine of plantation production in the Middle and Deep South of the republic. Commerce, labor, social stigmatization, expropriation of revenue, and punishment on a grand scale are foundational in the U.S. southern narrative of incarceration.

In The Nation’s Region: Southern Modernism, Segregation, and U.S. Nationalism, scholar Leigh Anne Duck astutely analyzes how the South’s imputed backwardness and refusal to “modernize” have served to reinforce a dubious “regionalist” definition of the nation. The telos of “regionalization” is to differentiate—putatively in the “national interest”—the abject, backward id formations of the South from the supposed rational and progressive modernization of the North. Economically grounded in plantation slavery, the South’s colossal wealth produced by servile labor and brutal punishment is something on the order of an “outside embarrassment” to northern religious protestations and boasts of “liberty for all.” The North’s penitentiaries hide punishment out of sight.

A myth of regionalism is not, of course, sustained and maintained solely by those who deploy it negatively and by projection to boost their positive image of the nation. Once crafted, as Duck and others have demonstrated, those who are vilified by myth may very well take up at least the exceptionalism of the myth as a point of pride. The South, that is to say, in both memory and present articulation, can proclaim its most redolently abject formations such as plantation chattel slavery a proud and defining institution, ordained by God and sanctioned by the laws of man. However, any memorial romance of the South’s “old plantations” bathed in southern charm would seem immediately to fade before the term “prison farm.”

The historical backstory of the South’s agricultural economies of labor and profit forms a longue durée commencing with the “gang production” of sugar as a cash crop in the Mediterranean. With European navigational successes such as the fifteenth-century voyages past the Cape of Bojodar financed by Portugal’s Prince Henry the Navigator, the West Coast of Africa became accessible for trade, expropriation of gold, and the securing of African bodies for labor. Sugar and other forms of plantation production (tobacco, rice, cotton) demanded monumental numbers of laborers in order to turn their greatest profits. The African slave trade produced such labor.

In minimalist description, one might say that in the transatlantic African slave trade, European and American trade goods and firearms were bartered in Africa for human bodies to be carried to African coastal barracoons or prisons. After the captives were factored or brokered to slave-ship captains for trade goods, they were packed into the dark holds of ships to endure the Middle Passage to New World plantations. From The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or, Gustavus Vassa, The African (1745) comes the following description of the “hold”:

The closeness of the place, and the heat of the climate, added to the number in the ship, which was so crouded [sic] that each had scarcely room to turn himself, almost suffocated us. This produced copious perspiration, so that the air soon became unfit for respiration, from a variety of loathsome smells, and brought sickness amongst the slaves, of which many died, thus falling victims to the improvident avarice, as I may call it, of their purchasers. This wretched situation was again aggravated by the galling chains, now become insupportable, and the filth of the necessary tubs, into which the children fell, and were almost suffocated.2

The Middle Passage could last as long as four months. Ships’ captains used “tight packing” methods—taking on hundreds of shackled African bodies, each allotted no more space than the length and breadth of a body on its side in a fetal position—to maximize profits. If there can ever be such a situation as “normal incarceration,” the Middle Passage certainly constitutes “X” or “Extreme Incarceration.” In The Slave Ship: A Human History, Marcus Rediker describes the overwhelming violence and constraints of the slave ships to which the “hold” was privy:

The slave ship was a strange and potent combination of war machine, mobile prison, and factory. Loaded with cannon and possessed of extraordinary destructive power, the ship’s war-making capacity could be turned against other European vessels. . . . The slave ship also contained a war within, as the crew (now prison guards) battled slaves (prisoners), the one training its guns on the others, who plotted escape and insurrection. Sailors also “produced” slaves within the ship as factory, doubling their economic value as they moved them from a market on the eastern Atlantic to one on the west. . . . The ship-factory also produced “race.” At the beginning of the voyage, captains hired a motley cr...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- PART I. REGIMES

- PART II. PLACES

- PART III. PEOPLES

- PART IV. APPROACHES

- PART V. STRUCTURES OF FEELING

- Works Cited

- Contributors

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Keywords for Southern Studies by Jon Smith, Riché Richardson, Scott Romine, Jennifer Rae Greeson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & North American Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.