![]()

1 FAMILY LAND

An American flag, sun-bleached, hung motionless from its pole on the front of the farmhouse. The air was humid. Thick like paraffin. The sky was clear, but Ed Scott Jr., seated behind an aluminum desk in his office, sensed gathering clouds. More thunder. And fire.

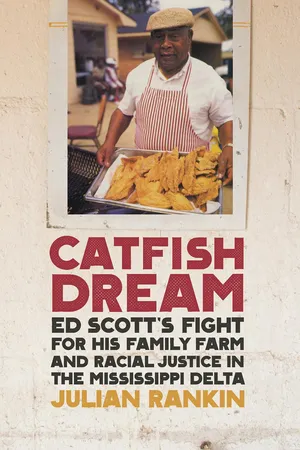

He reclined in a wooden chair, in a button-up shirt that read “Scott’s Fresh Catfish” tucked into jeans. Scott’s eyes darted. He inspected the familiar room and reviewed a mental checklist. Invoices peeped out of folders. More dust floated in the air, caught in the light, than he would prefer. Things needed doing. His belly hung slightly over his belt. He was a well-fed sixty-seven. He wore a farm cap on his head, and a mustache bristled above his upper lip. It was 1989.

Scott had bought the desk and the filing cabinets and everything else from an industrial office supply manufacturer. Thousands of other offices in a hundred other American industries probably had the same functional suite. Everything but the chair. Scott had been more particular about his swiveling desk chair. It needed a cushion, stature, and durability. Like Red Wing boots or a John Deere Model A tractor, whose own captain’s seat Scott considered the paragon. Things of quality like the chair need only be acquired once, Scott believed. They should last forever. Like family land.

The building in which Scott sat was a catfish-processing plant built in the remote open fields of Leflore County. Scott began with an emaciated tractor shed built by his father and fleshed out his catfish headquarters atop the bones with poured concrete, cinder blocks, and stainless steel hardware. When he first got into catfish he didn’t plan on having a processing plant. But Scott would become the first of his kind: the first African American to dig and stock his own catfish ponds and vertically integrate his business. It was a move forced by the discriminatory practices of agents of the U.S. government. It was a move that exposed the very core of the establishment’s bias.

Two ladies working with the Sunflower County Public Library in nearby Indianola sat across the table from Scott.1 One, the interviewer, took notes. The other juggled a camera rig. Scott had cut his errands short to meet them here. He drove fast on the way over. He was a fast driver. Once, Scott said, a state trooper pulled him over for speeding and fined him a hundred dollars. “Let me go ahead and give you two hundred dollars now because I’m coming back the same way.”2

The women thanked Scott for sitting with them. Scott answered that he didn’t mind. He had been looking forward to telling his story.

How did the Scott family wrestle control of all this land when so many of their peers struggled as tenants? the ladies wanted to know. Why weren’t there more like him?

In the Mississippi Delta, power is a stand-in for morality. The aldermen and commissioners and judges and cops and football coaches and landlords seem installed not by vote or appointment, but by on-high decree. They own the place. Here, what is rendered unto Caesar and rendered unto God go to the same P.O. box. Here, it’s hard to get it if you don’t already have it.

“Row crop farming was done in the early ages,” Scott began. “I started with my father and I give him and the Lord credit for everything I’ve done here.”

Scott gave voice to his father, Edward Sr., a man too busy to put his story on the record. Edward Sr. moved his family from Alabama to Mississippi in 1919. He worked shares in Glendora, around twenty miles away from the site of the future catfish plant. He sharecropped for nine years before he saved up enough to buy his first piece of farmland. In 1929, just before the Depression hit, Edward Sr. bought a new car. He built a garage and parked the Chevrolet inside, out of view, so that no one would know he had it. Edward Sr. did not hide his success—he protected it. Scott and his father shared the same aspiration: an American empire, for as many as it could feed.

“I left and went to the service in 1942,” said Scott, “and when I got out I bought this piece of land where I live now [from my father]. When he passed, the family owned 1,080 acres here. From sharecropper to landowner. We was the first people, in 1947, to start growing rice. And any change that came around in the farming industry, my father would change with it.”

The woman with the camera shifted the rig on her shoulder. The interviewer smiled at Scott as he spoke and nodded attentively. Scott took them to the early 1980s when he broke into the lucrative catfish business. Row cropping—mainly cotton, soybeans, and corn—fell away as the undisputed Delta moneymaker. Farmers looked elsewhere for financial viability. They excavated their fields and made fishponds. The government doled out huge loans. The catfish rush was on.

“But I built the ponds out of my pocket,” Scott added. No subsidy, his own equipment, and very little blueprint. He dug almost every day for a year. Eight ponds—160 endless acres of dirt—just outside the office window and across the dirt road from the house where Scott and his wife, Edna, slept.

To dig the ponds, three generations of Scott men relied on a variety of tractors and backhoes and machines and laser levels, including the Case, a brawny machine with big tread and a gritty engine that purred like a happy cat. By noonday sun and moonlight, the men carved out the grave-deep basins. They rattled behind the wheel for stretches of hours. The vibrations from the ride stayed with them after the day was done, a persistent internal hum that tingled the body.

The men dug in the spirit of the ancients, inverting the native people’s mound-building history during the Mississippi Period before Europeans arrived. They had constructed spiritual gathering places and celestial crossroads; Scott tamped terrestrial mud to hold his modern business. A neighbor could have watched the ponds take shape from across the road in the live oak shade of the Scott family cemetery—nearly a dozen scattered, moss-worn stones with epitaphs in various states of legibility. Edward Sr., at rest here, looked on.

“My motto is don’t stop chasing your dream,” said Scott. “And that was my dream. To grow these catfish. Which I did. . . . If I could’ve got the money to keep them going, you could expect $468,000 a year, and to operate the ponds after they were up and running would cost you $250,000 a year. Now you see how much profit. That’s why you get in the catfish business. Because it’s a business.”

Scott looked at the ladies, stuck on a thought. “Now let me tell you why I’m in this mess, which you really need to know.”

2 CHASING THE DREAM

Scott had ponds. He needed fish. He applied for and received a loan of $150,000 from the Farmers Home Administration (FmHA), a subsidiary of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA).

It wasn’t enough to fund the operation, Scott said. “Just enough to get me in trouble.”

It would take several hundred thousand dollars in the first year of the catfish operation to stock all the ponds with fingerlings, feed them out, and process them. Scott was able to stock only about half of his underwater acreage. He fed and raised the fish until they matured and were ready to go to market. Then he looked for somewhere to process them.

Delta Pride, a farmer-owned cooperative, processed more catfish than anybody. They’d opened a big plant 1981 in nearby Indianola and helped usher in the growing industry. But to process fish at Delta Pride, a farmer had to own stock in the company. When Scott tried to buy stock, he was denied. The reasoning, Scott recalled, was simple. He had the wrong color skin.

“Now you know what that did for me?” Scott said. “That said if the government was going to put money into something and I couldn’t get no stock in it, the government was no better than the people in Mississippi.”

Scott leaned forward and spoke softer. “You know, people used to think catfish was a salvage fish,” he said, acknowledging the reputation of the bottom-feeding channel catfish. “Wouldn’t nobody eat it. But now it’s the gourmet of the line.” Scott identified with underdogs.

With the door at Delta Pride closed to him, Scott built a facility of his own. When he opened his processing plant in 1983, it wasn’t automated. Workers hand-skinned until the company upgraded to band saws and stainless-steel tables and chutes and scales and conveyer belts. Hand-skinning was slower, but Scott and his crew could inspect and clean each fish thoroughly.

“Now everybody talks about how our fish tastes,” Scott said. “We take pride in our fish. When we first started cleaning fish, we used to wash the inside out with a brush. Every one of them. We took all the black lining out . . . and it really tastes better.

“I didn’t stop there. . . . We upgraded our plant in 1985 to what you see right now. Now we got seven skinners on the line, four head saws, got an eviscerator [to suck the guts out], everything that any other plant has. We have been inspected by USDC [U.S. Department of Commerce]. We can sell to anybody. . . . Right now we’re hitting the shores of California. We’re going to L.A. with it. Washington, Philadelphia, Chicago. We hope to go into vacuum packing and anything anybody else does in the next few months. Right now we have 34 full-time workers. We intend to expand our operation from 34 to 115.”

Within a few years the plant would close. Even at the time of the video recording, those ponds across the way weren’t full of fish. Scott was processing for other farmers and buying catfish—cash, a few at a time—to process and sell. The plan had been to stock the ponds and pond-hatch successive generations. But in 1983 the local FmHA office dubbed Scott’s business a risky venture and refused to extend him further credit. The government took all the fish, their bodies still writhing and flopping. FmHA had a lien on them and decided to call it in. Banks—which actually made the government-secured distributions—foreclosed on roughly a thousand acres of Scott’s farmland. The agency declined to restructure his loan or forgive his debt. Scott never farmed his own land again.

The ordeal began in 1978 when, after decades of farming, Scott heard that he could get this money from the government, which was pouring hundreds of millions into southern agriculture. Scott farmed with government money for a few short years. The decision proved costly. Whatever racial reconciliation had been realized since the middle 1960s wasn’t evident in the government statistics, which told of USDA’S continued disenfranchisement of black farmers. Scott’s momentum waned—even if he wouldn’t admit it to the interviewer in 1989. Every battle had been followed by another. After he lost his fish crop in 1983, he had no money left to restock. He bought fish from other farmers, Scott said, until FmHA issued veiled threats to those who sold fish to Scott. Scott held on to his ponds and his plant and his house. The rest he lost when the government foreclosed on him. The ponds would sit empty for the next thirty years. But the man persevered.

Scott took the ladies into the freezer room. The camera rolled. “Watch the floor, now. It’s wet,” Scott warned. “You cold?”

He pointed to a pallet jack stacked high. “You know where this is going?” Scott asked. The ladies didn’t. It was going to Alcorn State University, the historically black college in rural Claiborne County, Mississippi. “Three thousand dollars’ worth of fish going to Alcorn.”

They exited through the loading dock and walked back into the sunlight. Birds chirped. Scott pointed to four long concrete vats, a few feet deep and wide, that could each hold thirty thousand pounds of live catfish. This is where the live haulers offloaded, where the fish got stunned with electricity before the workers sent them inside the plant to the head saws. Water dripped slowly out of a spigot—not quite shut off—into the empty vat. “When the fish get in there in the summer the flies tend to bother them. . . . We keep the fish in this trough with water running on top of them so the flies won’t bother them at all.”

The strips of woodland that cut through the Delta farmland are full of critters in the high grass and water moccasins in shallow ditches. This is still wild land. It was tamed and made arable in the preceding century, but the frontier seems always to be rapping at the door. In the woods, when an animal dies, nothing happens right away. There’s no five-second rule. No one comes through to make sure the carcass meat makes it to the freezer. Carrion and scavengers and microbes don’t mind. Eventually the thing will be gone, picked clean and decomposed. Capitalism doesn’t give death such a wide berth. It mechanizes and feeds on it.

Scott believed the quality of his catfish depended on how quickly he could “chill him after you kill him.” Death was only the beginning, a station along the journey from pond to skinning table to box in the Kroger freezer. Scott was generally impatient with nature’s pace. He preferred direct action to passive voice, lucid vision to aimless dream. Henry Ford, Scott knew, had changed the world by harnessing man’s engineering potential. Scott had a mind to do the same.

Before the crew left, the interviewer asked Scott what he would like to tell his great-great-grandchildren, knowing that the tape would be archived in the county library.

“Well if it’s going in the library, I’d like to say to my people: It ain’t no such thing as ‘you can’t do what you want to do’ if you want to do it bad enough. If you put your hand and heart to anything you want to do, you can ...