![]()

ORDINARY LIVES IN THE

EARLY CARIBBEAN

Religion, Colonial Competition,

and the Politics of Profit

KRISTEN BLOCK

![]()

CONTENTS

List of Figures

Acknowledgments

Introduction

PART I Isabel: “If Her Soul Was Condemned, It Would Be the Authorities’ Fault”

1 Contesting the Boundaries of Anti-Christian Cruelty in Cartagena de Indias

2 Imperial Intercession and Master-Slave Relations in Spanish Caribbean Hinterlands

3 Law, Religion, Social Contract, and Slavery’s Daily Negotiations

PART II Nicolas: “To Live and Die as a Catholic Christian”

4 Northern European Protestants in the Spanish Caribbean

5 Empire, Bureaucracy, and Escaping the Spanish Inquisition

6 Conversion, Coercion, and Tolerance in Old and New Worlds

PART III Henry: “Such as will truck for Trade with darksome things”

7 Cromwellian Political Economy and the Pursuit of New World Promise

8 The Politics of Economic Exclusion: Plunder, Masculinity, and “Piety”

9 Anxieties of Interracial Alliances, Black Resistance, and the Specter of Slavery

PART IV Nell, Yaff, and Lewis: “He hath made all Nations of one Blood”

10 Quakers, Slavery, and the Challenges of Universalism

11 Evangelization and Insubordination: Authority and Stability in Quaker Plantations

12 Inclusion, the Protestant Ethic, and the Silences of Atlantic Capitalism

CONCLUSION Cynicism and Redemption

13 Religion, Empire, and the Atlantic Economy at the Turn of the Eighteenth Century

Notes

Index

![]()

FIGURES

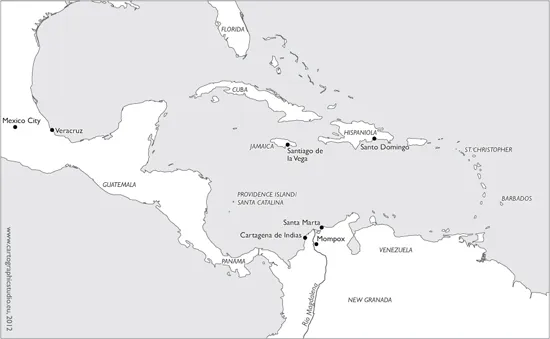

| 1–2 Modern views of Cartagena de Indias’s

principal cathedral and Inquisition Palace |

| 3 Modern view of the Jesuit Colegio in Cartagena’s Plaza San Pedro Claver |

| 4 Engraved portrait of San Pedro Claver (Marcus Orozco, 1666) |

| 5 Plan of the city of Cartagena de Indias (1735) |

| 6 Engraved view of Sir Francis Drake’s attack of Cartagena (Boazio, 1588) |

| 7 Modern display of the rack in Cartagena’s Inquisition Museum |

| 8 Portrait frontispiece to The world encompassed by Sir Francis Drake (London, 1628) |

| 9–10 Modern views of Cartagena’s San Felipe fortifications |

| 11 Illustrated frontispiece to Tears of the Indians

(London, 1656) |

| 12 Dutch engraving, “English Quakers and tobacco planters in Barbados” (ca. 1700) |

| 13–14 Map of Barbados (Richard Forde, 1675), with detail showing Morris landholdings |

| 15 “An Abstract of the Sufferings for Conscience sake of the People called Quakers, in the Island of Barbados” (1696) |

| 16 “Lucifer’s New Row-Barge,” a satire of the South Sea Bubble (ca. 1721) |

| 17 –18 Pirate cruelty, engravings from Exquemelin’s Buccaneers of America |

![]()

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Projects like this often seem interminable, in part because they are collaborations of the largest magnitude. During the long years in which this book moved from concept to reality, I have accumulated many friendships as well as debts of gratitude that I’d like to recognize here. Financial support for research and writing of this project from dissertation to book include fellowships at the John Carter Brown Library supported by the InterAmericas and Ruth and Lincoln Ekstrom trusts, a semester-long fellowship at the Charles Warren Center for Studies in American History at Harvard University, a W. M. Keck Fellowship at the Huntington Library, a Barra Foundation Fellowship for a year of dissertation writing at the McNeil Center for Early American Studies at the University of Pennsylvania, and a semester as a visiting instructor for the Department of History at Beloit College, Wisconsin. Several smaller (but no less vital) travel grants—from the Department of History at Florida Atlantic University, the American Historical Association, Spain’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores de España), Harvard’s International Conference for the History of the Atlantic World, and the Graduate School at Rutgers University—helped make my ambitious research agenda possible. Special thanks to the directors and administrators of those funding agencies, especially Bernard Bailyn, Pat Denault, Norman Fiering, Ted Widmar, Valerie Andrews, Bob Hodge, Eula Buchanan, Pilar Lopez Quintela, Heather Pensack, Elizabeth Thomas, Daniel Richter, Amy Baxter-Bellamy, Patricia Kollander, Zella Linn, Susi Krasnoo, Carolyn Powell, Joyce Chaplin, Larissa Kennedy, and Arthur Patton-Hock. I would also like to thank my academic community in South Florida—especially Ashli White at University of Miami, Jenna Gibbs at Florida International University, and Philip Hough at Florida Atlantic University—for providing venues to meet and discuss my writing with other interested scholars.

Several close friends and colleagues have read and commented on early versions of various chapters, and for that I am eternally grateful. Special thanks to Nadia Celis, Marisa Fuentes, Kate Keller, Anna Lawrence, Jenny Shaw, Margaret Sumner, Kathy Wheeler, and Derrick White for helping me find clarity and confidence in my work. Those whose mentorship and encouragement sparked my journey into the historical profession deserve special recognition: Linda Sturtz and James Robertson; and Phyllis Mack, Christopher Brown, Herman Bennett, Jennifer Morgan, and Jane Landers. During my travel and fellowship stints, I had the privilege of meeting many established scholars whose advice and conversations helped shape the direction of my research and writing: Vincent Brown, Brycchan Carey, Antonio Feros, Sylvia Frey, Amy Froide, Ignacio Gallup-Diaz, Allison Games, April Hatfield, Karen Kupperman, Joseph Miller, Stuart Schwartz, and Enriqueta Vila Vilar. Others who, in ways too numerous to describe in detail, helped enrich or otherwise made it possible to complete this book: Moisés Alverez Marin, Jenny Anderson, Padre Tulio Aristizábal, Allison Bigelow, Carmenza Botero, Asmaa Bouhrass, Martin Bowden, Andrea Campetella, Nana Castello Salvador, Joanne Carter, Lina del Castillo, Carol Cook, Kaja Cook, Christian Crouch, Graciela Cruz Lopez, Stephanie Dodge, Lesley Doig, Marcela Echeverri, Olga Fabiola Cabeza, Lupe Fernandez, Adrian Finucane, Charley Foy, Jorge Gamboa, Diego Garcia Marquez, Katie Gerbner, Carolina Giraldo, Jaime Gomez Borja, Pablo Gomez, Esther Gonzalez, Larry Gragg, Piedad Gutierrez, Karen Graubart, Carina Johnson, Heather Kopelson, Chris Lane, Carla MacDougall, Becka McKay, Javier Mije, Catherine Molineux, Elena Machado, Alfonso Múnera, Karl Offen, Katrina Olds, Alejandra Osorio, Heather Peterson, Amanda Pipkin, Juan Ponce-Vázquez, Joanne Rappaport, Suzanna Reiss, Adriana Maya Restrepo, Esteban Reyes, Linda Rupert, Lucely Salgado, Eric Seeman, Kate Schmidt, Renée Soulodre-La France, Hilit Surowitz, Greg Swedburg, Abby Swingen, Mauricio Tovar, Jennifer Troester, Karin Velez, Karl Watson, David Wheat, and Emily Zuckerman. Finally, I must thank those who reviewed my entire book manuscript for their generous feedback and suggestions for revision. Derek Krissof has been a wonderfully supportive acquisitions editor and a perceptive reader. Thanks also to Tim Roberts, Gary Von Euer, and the entire team working with the Early American Places series for their help with the miraculous transformation into book form. The flaws that remain in this book are entirely my own, but I know that there would have been many more without the time and effort of all those individuals who helped inform my ideas and sustained my spirit.

This book is dedicated to my family—Joseph and Connie Block, and Karl, Jackson, and Caden Block—and to my friends and mentors. Each and every one of you contributed fundamentally to my growth as a thinker, as a scholar, and as a person. I hope each of you will see a small part of the insight and love you provided reflected in this book.

![]()

Introduction

This book tells several stories. The first follows Isabel Criolla, a runaway slave who stood before the Spanish governor of Cartagena de Indias and begged him not to return her to her cruel mistress, saying that if she was sent back she would be either driven to suicide or would be beaten to death and die without confession. Isabel warned him that “if her soul was condemned, it would be the fault of the authorities.” He heeded her words.

Another story is about Nicolas Burundel, a French Calvinist who served the Spanish governor of Jamaica as a servant-henchman. When the parish priest led a religious procession down Santiago’s city streets, Nicolas had to pull off his cap and bow before the Corpus Christi or the image of the Virgin, knowing that many suspected him of being a heretic and would be watching to see how he comported himself.

A third story follows a sailor named Henry Whistler to the Spanish island of Hispaniola, watching with him as a company of rough-and-tumble English soldiers hurled oranges at a statue of the Virgin Mary they discovered in one of the island’s abandoned chapels, laughing as they stabbed the statue’s darkened face, mocking the Spaniards who must have used it “to enveigle the blacks to worship.”

Finally, this book envisions the lives of Yaff and Nell, an enslaved man and woman in the service of a Quaker planter in Barbados named Colonel Lewis Morris, all three of whom struggled to live in a world based on coerced labor without losing their sense of shared humanity. In addition to their regular duties as household servants, Yaff and Nell attended instructional and worship meetings, learned about their master’s definition of morality, and perhaps dreamed that this knowledge would lead to a better life for them and their children—a way to lessen the prejudice that assumed they were immoral, unworthy, “natural” slaves.

I tell these stories so as to examine Christianity as a force for social inclusion and exclusion in the early Caribbean, centering on the struggles of ordinary people to survive in this burgeoning capitalistic world. By following enslaved people of African descent and lower-class whites—those at or near the bottom of the socioeconomic ladder—I illustrate how each actively engaged with the rhetoric and rituals of Christianity to create alliances that might help them in their search for justice and opportunity. However, telling the story of their lives together also shows how racial categories began to trump shared religious identities by the end of the seventeenth century, a shift that especially constricted opportunities for economic and social belonging among people of African descent. This change was more marked in the British than in the Spanish colonies, and had as much to do with economics as it did with religion. As the balance of Caribbean power sh...