![]()

1 / “An Heathenishe, Brutish and an uncertaine,

dangerous kind of People”: Figuring Difference

in the Early English Atlantic

On a September afternoon in 1661, Sir Henry Walrond placed his signature on the “Act for Better Ordering and Governing of Negroes.” Following the upheaval of the interregnum, Walrond and the Barbados Assembly had put together the first comprehensive set of laws that would regulate slavery in their colony. Such action was necessary. Given that the “Laws of England” had offered “no Tract to guide us,” the assembly members had instead collected the various orders approved over the preceding decades by island legislators into one document. Purporting to guard enslaved laborers “from the arbitrary Cruell and outrageous will of every evill disposed person,” the laws instead codified Africans as chattel and provided more protections for their owners than for the subjects of the legislation. To ensure that there was no confusion about the differences between servitude and slavery, on the same day Walrond also placed his signature on the “Act for Good Governing of Servants, and Ordering the Rights between Masters and Servants.” After all, just two years earlier the Protectorate government had been rocked by the suggestion that Englishmen were being treated as slaves. The recently restored government on Barbados wanted to avoid any such accusations, drawing a definitive line between those who would labor for life and those who would be contracted to work for a set number of years. The 1661 slave code identified the Africans who fell into the first category as “an Heathenishe, Brutish and an uncertaine, dangerous kind of People,” underscoring the clear distinctions between the “negroes” of the act’s title and both the civilized elite English who wrote the laws and those who fell into the second category, “servant,” whose status in the legislation was often modified by the descriptor “Christian.”1 This conflation of religious and ethnic descriptions was a common practice among English officials across their Atlantic world.

The laws of 1661 are just one example of how England’s colonial ventures forced English imperialists to find new ways to define difference. Ireland, the site of England’s first imperial project, provided a fruitful “laboratory for empire,” where English ideas about superiority and civilization were first worked out by those men charged with governance of the island.2 While the Irish were not the only colonial population to shape these English theories, experiences in Ireland were nonetheless foundational to how the English read and understood distinctions elsewhere. Moreover, many of the lessons learned (and ignored) in Ireland informed English colonial policy in the Americas, including the ways that the English discussed non-English subjects.3 Discourses about Irish inferiority certainly had their parallels in English descriptions of the poorer sorts of their own compatriots, but in a post-Reformation world it was the Catholicism of the Irish combined with their supposedly irregular customs that marked the island’s population as fundamentally apart from English civilization. English observers, colonists, and commentators in Ireland used these ideas about inherent Irish difference to justify the poor treatment of the Irish Catholics they colonized and to lay claim to Ireland itself.

In the Caribbean English attempts to define difference took on new challenges. English colonists (like their compatriots throughout the Americas) did their best to replicate the England they had left behind. But for all that they tried to create a “little England” in the West Indies, authorities were forced to reckon with a set of circumstances very unlike those they encountered at home.4 Cash crop production was so central to the financial success of the colonies that the issue of labor pushed its way to the top of the imperial agenda. Although at first the workforce on the islands was composed largely of English indentures, very quickly enslaved Africans and laborers from other parts of the Three Kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland became the predominant sugar-producing forces on the islands, with the Irish making up the lion’s share of non-African workers.5 The presence of these populations significantly altered demography, making the Caribbean inescapably different from England. It also raised the question of the status of these laborers, particularly with respect to the growing institution of slavery. There was no English common law to rely on when it came to questions of bondage, so colonial assemblies, like the one on Barbados, had to create legislation wholesale to deal with the system of slavery. The laws that assemblies produced reflected a tension in elite English concerns about how to order society. While their understandings of hierarchy come through in the sources, lawmakers were caught between emphasizing Christianity as a signifier of difference and accentuating distinctions based on a variety of other cultural and ethnic markers.

Arguments made by English elites in the 1650s that privileged Protestant Christianity as the arbiter of freedom were later displaced by reasoning that had a more racially motivated analysis at its heart. The shift took place in stages, and there was no strict progression from one position to the other. Part of the reason for the uneven transition lay with English lawmakers, who initially cleaved to ideas about difference determined on the basis of potentially malleable cultural practices rather than supposedly inherent and unchangeable biological realities. Cultural difference, they believed, could be overcome, so Irish Catholics might adopt the practices of Protestants, and heathen Africans might be able to imitate good Christians. Ultimately, however, English elites realized the dangers that such ideologies posed. To maintain their hierarchy of labor they needed an underclass who could be subjected to various degrees of bondage. Encouraging Irish Catholics and enslaved Africans to transform might cause them to challenge their subservient status or no longer render them suitable for servile labor. And in any case, such metamorphoses would always be suspect, exacerbating elite fears about trouble-causing populations in their midst. The English recognized another threat contained in these discourses about difference: if non-English subjects could be transformed, they reasoned, then perhaps the English could be too, and not necessarily for the better. Laws regulating sexual and religious norms and identifying disruptive behavior on the islands raised the potential for English colonists to be corrupted by other groups, recalling the degeneracy of the Old English in Ireland. These descendants of the Anglo-Norman invaders of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries had risen to various positions of prominence on the island but were now accused of having “gone native” as a result of their exposure to the island’s indigenous inhabitants.6 So legislators moved to construct discrete categories and to legislate against the coming together of people from different religious or ethnic groups.

This chapter explores elite English struggles to fix categories of difference in the early modern Atlantic world through three sets of elite constructed sources that reflect their everyday experiences in Ireland and the Caribbean. It begins with the 1659 petition of two English gentlemen who argued that Englishmen in Barbados were being treated as slaves, and it follows the resulting parliamentary debate about whether Englishmen, even those who had taken up arms against the government, could be held in perpetual bondage. Next, the travel writing and observations of elite English in Ireland are investigated for what they reveal about classification on the site of England’s first colonial venture. Discourses about differences in Ireland based on cultural practices—land use, sexual mores, clothing, and religion—paralleled English discussions about the people they encountered in the Americas and Africa during campaigns of colonization and exploration. These ideologies influenced the processes of defining difference in Caribbean settings, so the legal system that developed in Barbados and the Leeward Islands created hierarchies according to sex, labor, religion, and ethnicity. Although there are no extant transcripts of the debates that colonial assemblies engaged in as they wrote their legal statutes, the laws themselves provide context for the struggle that ensued, insofar as legislation responded to the vagaries of everyday life in the colonies.7 Laws constructed by elites were therefore somewhat schizophrenic: some mirrored ideas about difference carried over from Europe; others reflected issues specific to life in the Caribbean; many combined elements of both.8 Irish Catholics sat at the intersection of each of these discussions, whether they were in European or American settings. Paying attention to the space they occupied in between ideas separating African from English, heathen from Christian, and even black from white provides a window into the mechanisms through which the English figured difference in their early modern Atlantic world.

“By which you may discover whether English be Slaves

or Freemen”

The radical demographic shifts of the 1650s that saw an increase in African captives and prisoners of war from England’s civil conflagration entering into the Caribbean spurred a debate over the treatment of laborers in the English Caribbean that drew in participants from both the metropole and the colonies and that was grounded in the everyday experiences of the protagonists.9 There was a larger context to these deliberations: for almost two decades the English had been embroiled in their own struggles at home as a sequence of bloody civil wars shook the country and its surrounding kingdoms to their core. At the heart of the conflict were questions of authority and tyranny, as the supporters of Parliament (Roundheads) challenged the supremacy of the monarchy and its royalist allies (Cavaliers). But even when parliamentary forces prevailed and beheaded Charles I in 1649, questions of control continued. Oliver Cromwell, hero of the New Model Army, was declared Lord Protector of England, Scotland, and Ireland by Parliament in 1653, taking on a role in the republic that closely mirrored that of a monarch. An uneasy relationship with Parliament followed, as some fervent Roundheads believed Cromwell to be too authoritarian. These troubles continued when his son, Richard Cromwell, took charge of the Protectorate upon Cromwell’s death in 1658.10 Within the year, debates in Parliament reflected the tensions raised by the Cromwellian regime as some in the republic attempted to distance themselves from what they saw as the tyranny of the previous decade. It was in this turbulent context that a petition from two English gentlemen was heard in the restored Rump Parliament.

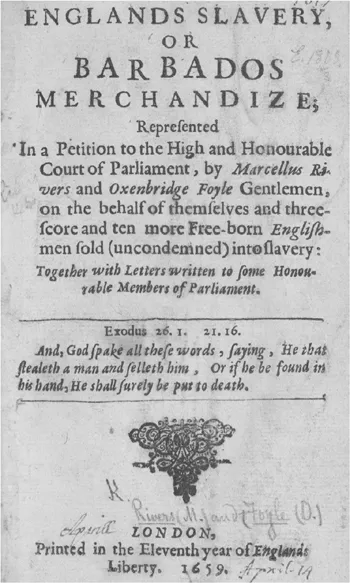

In 1659 the English gentlemen Marcellus Rivers and Oxenbridge Foyle, who had been banished to Barbados for their part in a royalist uprising against the Protectorate, published a pamphlet entitled Englands Slavery, or Barbados Merchandize accusing the government of having “sold (uncondemned) into slavery” some “three score and ten more Free-born Englishmen.”11 Included along with the petition were four additional letters of appeal, all authored anonymously by royalists, and all decrying the experiences the writers had endured. The pamphlet stressed the innocence of the victims of transportation, detailed their harsh treatment in the Caribbean, and made direct comparisons between the fate of the men accused of taking part in the Salisbury Rising of 1655 and that of the enslaved Africans who labored on plantations by carefully charting the similarities of their everyday experiences. As Susan Dwyer Amussen has argued, Rivers and Foyle made their case on the basis of the illegality of all that had proceeded.12 Even if their arrest and imprisonment could be understood as an oversight or a mistake in a time of civil war, the government had overreached, had condemned English men, and gentlemen at that, to service in Caribbean sugar fields: they had been “Barbadosed” like men from the lowest orders of society.13

Perhaps understanding that the question of whether fellow Christians could be enslaved was likely to be decided in their favor, Rivers and Foyle (and their anonymous co-correspondents) framed their petition as an affront to their status as Protestant Englishmen. On the front of their pamphlet they cited a biblical admonition against slavery: “And, God spake all these words, saying, He that stealeth a man and selleth him, Or if he be found in his hand, He shall surely be put to death.”14 The men also laid out the uncivilized treatment they received (being sold like livestock, being worked to the bone, suffering poor living conditions, being whipped “for their masters pleasure”), characterizing their handling as “beyond expression or Christian imagination.”15 These themes were emphasized by the anonymous co-petitioners, one of whom described Barbados as “the Protestants Purgatory” and drew on a popular Calvinist outcry—“Quousque domine quousque”—to emphasize his Protestant education and beliefs, and another who described the destinations of the prisoners as “heathenish.”16 And lest all these pleas to Parliament on the basis of shared religion go unnoticed, Rivers and Foyle ended their petition by unfavorably comparing the treatment they had suffered under the English with the actions of “cruell Turks” who despite their infidel status would not stoop so far as “to sell and enslave these of their own Countrey and Religion.”17 To them, the notion that one could place another person of the same Protestant faith in bondage was appallingly cruel. By drawing on religious arguments, the petitioners underscored their own Protestant Christianity: the unspoken counterpoint was the heathen Africans with whom they labored.

FIGURE 1. Title Page, Englands Slavery or Barbados Merchandize, 1659. General Reference Collection E. 1833. (3) © The British Library Board.

There can be no doubt that the choice by Rivers and Foyle to emphasize the similarity of their experiences to those of enslaved Africans was strategic, “a calculated attempt to shock” the parliamentarians who debated their fate.18 Making the implicit case that they were being treated as heathens, the men stressed the similarity of their middle passage and experiences on Barbados to those endured by Africans.19 Held captive against their will, the men were “snatcht out of their prisons … and driven through the streets of the City of Exon,” much as African captives traveled in slave coffles through the streets of Whydah or Accra to the coast to board ships.20 The anonymous author of the “fourth Letter” described how he had been “stifled up, for a whole year,” before his transportation.21 Being held prisoner before being taken to a ship recalled the kinds of scenes that occurred at slave forts like Elmina, where enslaved Africans could be held for months in dungeons before they moved through the Door of No Return to depart on vessels destined for the Americas.22 And once they were on the ocean, the similarities continued: the men were “kept lockt under decks (and guards) amongst horses,” in much the same manner as enslaved people.23 Unlike servants who voluntarily headed to the Americas, or sailors aboard ships, the captives were not given hammocks to sleep in but (in the same way as captive Africans) were “forced to ly on the bare hard boards, they refusing to let us to have so much as mattes to ease our weary bones.”24

Like Africans kidnapped or captured as the spoils of war, these English petitioners were also war captives, removed from their families and communities without notice, or warning, “none suffered to take leave of them.” Indeed, after almost six weeks at sea, the men noted that they were now “four thousand and five hundred miles distant from their native countrey, wives, children, parents, friends, and all that is near and dear unto them.” The men emphasized their feelings of loneliness and separation due to their complete dislocation from the life they had had before. One of the anonymous petitioners wrote at length about t...