![]()

Part I

International Contracting: Defining

The Playing Field

![]()

Chapter 1

International Contracting: How a

Project Can Turn into a Nightmare

1.1.Case — An uneasy event

On April 20, 2010, a range of explosions crippled the Deepwater Horizon. Flames spread rapidly, power went down. Eleven men lost their lives, seventeen were seriously injured. The economic loss amounted to tens of billions of dollars. BP had to set aside $40 billion to compensate for damage to third parties. The BP Oil Spill probably has grown into the biggest disaster in offshore contracting. The story is as incredible as are its lessons. Figures 1.1 and 1.2 show the giant module in perfect condition before the disaster and when it burned before going down to the bottom of the Gulf of Mexico.

The literature about project management and risk management is abundant. Most project managers are familiar with the basics of project and risk management — they practice them every day. Rather than discussing what it takes to implement professional project and risk management, we have decided to present these topics via an actual case study to show the gap between theory and practice that often exists. We use the BP oil spill as an example. The next sections discuss what actually happened and what went wrong when testing the production pit. We also describe how the contract partners and stakeholders reacted when things went wrong and when they were brought to investigation committees for initial interviews. We conclude the chapter with the important lessons that can be learnt from this dramatic case study. In doing so, this chapter sets the stage for the remainder of the book.

1.2.The BP oil spill: what happened?

BP contracted a number of parties to prepare a well for exploration. The two most important partners were Transocean and Halliburton. Transocean delivered the platform and technical installations under a long-term contract. Halliburton was responsible for providing and installing the cement, as described in Box 1.1 and under Figure 1.4. BP was the legal operator, whilst all oilfield service activities were subcontracted to specialist companies.

Figure 1.1. The Deepwater Horizon before the disaster. (Photo: Transocean Inc., 2013, www.deepwater.com/fw/main/lDeeptwater- ….. - 419C151.html.)

Figure 1.2. The Deepwater Horizon burning on April 22, 2010, before it sank to the sea bottom in the Gulf of Mexico. (Photo: www.crisispictures.blogspot.com, courtesy Bojar Baretic, February 2013.)

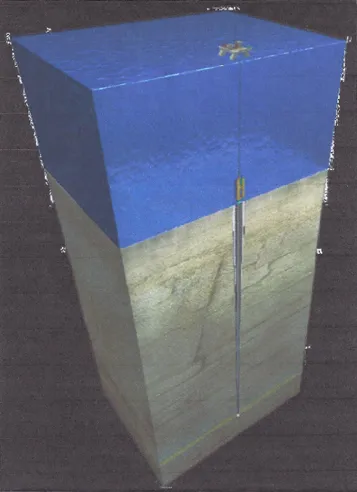

With the help of the Deepwater Horizon, BP arranged for drilling a well, enabling access to the oil reserves of the Macondo area at a depth of 5,500–6,000 meters below sea level. Locally, the sea floor is at about 1,500 meters below sea level. A special multitubular casing was drilled through three different layers in the soil in order to arrive at the oil and gas layers (see Figure 1.3). Care was taken so that the oil and gas would not come to the surface. This was arranged by injecting a heavy drill fluid (“mud”) in the drilling pipe. During the production phase, which was planned to take place later on by a different production platform, the oil and gas would come upwards through the central metal riser. The outside casing and the inside metal tubing were, at the time of completion of the drilling, blocked by cement to prevent oil and gas coming up. Injecting the cement was contracted to Halliburton. Right on the sea floor a blowout preventer (BOP) was mounted. This important piece of apparatus was part of Transocean’s equipment. It was designed and manufactured by Cameron.

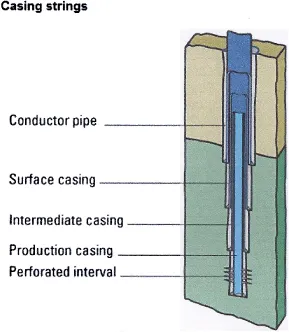

Box 1.1. Casing and tubing below sea level.

Figure 1.4 shows the casing and the inner pipe under the sea bottom. The casing together with the central production tubing penetrates three different layers under sea level before arriving into the oil- and gas-bearing layers. The central tubing was intended, in the future, to transport the hydrocarbons up to a production platform and, therefore, is called the production tubing. The casing, when coming to depth, has smaller diameters. When mounting the casing and the inner piping, heavy drilling liquid is put into it in order to prevent oil and gas blowing out. Later on cement is poured between the casing and the central transport tubing. Cement is also put on the well annulus at the lowest possible point of the production pipe and outer casing. The tightness of the cement is verified by means of a pressure test. If the pressure test shows negative results (which indicates that the casing and production tubing have been effectively closed), the heavy drilling liquid can be changed for sea water, which is much lighter than the drilling liquid.

Figure 1.3. The BP well design and the drilling platform above; the object on the sea floor is the blowout preventer. (Source: Artist rendering of the Macondo well from rig to ‘rathole’, National Commission on the BP Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill and Off Shore Drilling, Chief Counsel’s Report, February 17, 2011, p. 53.)

Figure 1.4. Schematic view of drilling pipe design. (Source: Oil and Gas Dictionary, January 2013.)

BP’s engineering team designed the well and specified in detail how it had to be drilled (see Box 1.1). BP contracted out the work. On April 20, 2010, only 7 out of 127 persons on board the platform were BP employees.

1.3.The test

It is common practice to test the closure of the well through a pressure test. Engineers call such a test a negative pressure test. If nothing happens the result is positive. The cement down the casing and the production tubing should be sufficiently tight to resist all pressure from the oil and gas below. Cement is the barrier. In the event hydrocarbons could have penetrated between the outer casing and the production tubing a second barrier was in place. A strong seal underneath the BOP should prevent oil and gas passing through the tubing — this BOP is the third barrier and could be closed in the event hydrocarbons would, unexpectedly, come to the surface through the production tubing or through the outer casing.

After the “successful” pressure test, the crew started to replace the heavy drilling fluid with sea water. This is much lighter than the heavy drilling fluid. In the event oil and gas penetrated the cement, this would be recorded by an increase of the pressure, which would mean that the cement was still insufficiently tight. If a rise in the pressure was registered, measures could be taken to interfere on time.

After testing, everything seemed to be under control. Obviously, the well passed the test in good order. Things appeared to be okay and the well site leader concluded that the operation was successful…

The reality was quite different. There were leaks. However, these remained unobserved due to the fact that procedures were not followed, and also to an unclear line of command among the parties involved. As the crew replaced the drilling fluid with sea water, the pressure on the well was reduced. At 20:50 hours, the well became unbalanced. The weight of the lighter sea water could not resist the pressure of the gas deep down. Suddenly, the oil stream pushed the cement upwards, taking parts of it with it on its way to the surface. The BOP refused to operate. First, enormous quantities of mud, cement and sea water spread out on the drilling deck. Shortly afterwards, the dangerous methane gas escaped and found an ignition source. Methane is heavier than air and probably could have entered through ventilation openings to arrive in the engine room, where several hot objects of machinery, such as diesel engines, were operating. This set the methane gas on fire. Now the oil came up, burning the giant platform to total destruction within a mere 36 hours. When the $365 million rig slowly sank to the sea floor on April 22, oil and gas continued to flow from the open well underneath into the open waters of the Gulf. It took 87 days to get that stopped. As noted above, BP had to put aside $40 billion as compensation for claims for damages.

What can we conclude from this story so far? Firstly, all parties involved, i.e. BP, Transocean, Halliburton and others, including the subcontractors, are experienced contractors who are familiar with drilling and offshore operations. All parties have extensive procedures on health, safety and environmental issues. All parties are professionals in risk management. This is particularly true for a company like BP, which does not make any major investment decision without a thorough risk analysis. Obviously, safety procedures were set aside or were not followed with sufficient diligence.

Many parties needed to work closely together. However, they obviously failed to do so since the line of command was not entirely clear to them. Obviously, subcontractors were (or felt) overruled by the BP engineers who actually decided what needed to happen. It is a fact that, for reasons that were unclear, parties decided to deviate from standard routines.

1.4.The first investigations

Two weeks after the disaster, public hearings before the US Senate were held. A public investigation before a joint Coast Guard and Interior Department Commission started. The US Departments of the Interior and Homeland Security started an investigation to assess the damage on land. The US Department of Justice put a team of lawyers on the case to investigate criminal liability of companies and individuals. President Barack Obama installed a special committee to investigate the disaster.1 This was “an independent non-partisan entity, directed to provide a thorough analysis and impartial judgment”.2

Immediately after the first hearings of the US Senate and the Joint Coast Guard and Interior Department Commission, and after the Wall Street Journal interviewed dozens of witnesses to the disaster, this newspaper reported on how risks were estimated by BP’s responsible chiefs-in-command and how opinions from specialized service providers were misjudged.3 What emerged was a startling picture of the last operating day of the Deepwater Horizon. Later on, the preliminary conclusion was confirmed by the National Commission in its report in January 2011. The commission found that BP, contractors and subcontractors working for them had conducted a number of hazardous and time-saving activities, without adequate considerations of the risks involved. Their report concludes:

…There are recurring themes of missed warning signals, failure to share information, and a general lack of appreciation for the risks involved. In the view of the Commission, these findings highlight the importance of organizational culture and a consistent commitment to safety by industry, from the highest levels on down.4

The Chief Counsel’s report, when describing his technical findings, is in line with these observations, when it states: “Behind this simple story is a complex web of human errors, engineers in misjudgment, missed opportunities, and outright mistakes.”5

The BP drilling operation appeared to be way over budget and far behind schedule. The budget was exceeded by $20 million on the original sum of $155 million, while the planning schedule was 43 days behind. BP’s contract required it to pay approximately $533,000 per day for the charter of the platform. In addition to that amount was fuel, expenses, salaries, service providers and suppliers. It was estimated that the total cost for BP amounted to about $1 million per day. Members of the Congress, industry experts and workers on board accused BP’s engineers of having cut corners to save time and money.

Drilling was finished 11 days before April 20, and...