![]()

1.

What are Bubbles and Financial Crises?

1.1 Introduction

Financial crises are not new. The first documented ones are the Dutch Tulip Bubble and its painful crash in 1637, and the South Sea Bubble of 1720, when even Sir Isaac Newton lost a fortune. Between the years 1816 and 1866, such crises occurred once every ten years or so.

Although historically each crisis is different, the science of economics seeks to identify lines of similarity between different crises and to formulate a model that describes, albeit in general terms, the different stages along which a typical crisis evolves. This chapter illustrates the key ingredients of a financial crisis by highlighting a few notions of a model developed by Prof. Hyman Minsky. Only financial systems based on free-market principles will be discussed, i.e., crises that have occurred in economies run by a central planner will not be analyzed.

1.2 A Conceptual Framework of Financial Crises

The pace of growth in a market-based economy is often measured as the percentage chance in gross domestic product (GDP). This pace of growth, or ‘growth rate’, is not fixed but rather cyclical; sometimes rapid, sometimes slow, there might be periods of zero growth, and even negative growth. In other words, the economy expands and shrinks in a process known as the ‘business cycle’. In times of rapid economic growth, there is generally a rise in credit, and specifically loans are extended by the banking system to households and firms. On the other hand, when the business cycle is at low tide, a reduction in credit is usually seen. The positive correlation between the credit cycle and the business cycle is an important starting point in Minsky’s model.

Hyman Minsky (a Professor of economics at Washington University in St. Louis, 1919–1996) believed that the expansion process of a business cycle is accompanied by optimism among most investors regarding the expected profitability level of enterprises in which they invest. Therefore, they are willing to take out larger loans and invest in more risky enterprises. At the same time, the optimistic atmosphere overtakes lenders who are therefore ready to lend more and finance even riskier enterprises. However, the optimistic phase of the business cycle is ultimately replaced by a pessimistic phase, and the fall in the value of investments gives rise to bankruptcies and a partial loss of previously extended loans. Irving Fisher, one of the most prominent economists of the 20th century, believed that a financial system is liable to significant risk when large borrowers take out particularly large loans to fund purchases of real estate, stocks or other assets due to speculative motives. That is to say, the motivation is buying today with the intention of selling the asset later, hopefully reaping a capital gain.

The term ‘speculation’ will be used frequently throughout this book, with the following definition: The word ‘speculation’ is derived from the Latin word specula, which means ‘observation tower’. Just as a watchman in a tower sees further than one on the ground, the speculator similarly presumes to see several moves forward, predicting future prices. The speculator will buy today if the price is expected to rise, and sell today if the price is expected to fall. If they guess correctly, the speculator will benefit from a ‘capital gain’ (the difference between the selling price and the purchase price). Note that on the other hand, a non-speculative investment is one intended to profit mainly from the yield of a capital asset, i.e., coupon interest on bonds, dividends paid out on stocks, rental revenue from real estate or the utility worth yielded by the apartment one lives in. Nevertheless, if there is no profit but rather a loss, then that large borrower rolls over the losses to the unfortunate lenders and gives them a ‘haircut’, i.e., he pays back only part of the debt.1 True, one can get a haircut even when investing in non-speculative bonds, but the risk is lower.

Because asset prices change as new information hits the market — with negative information reducing the price and positive information increasing it — a speculative investment is considered risky. To illustrate, consider a speculator who purchased an asset in anticipation for a price increase, but a random, unexpected news event reduces the price. This speculator might lose on the transaction, therefore act to immediately sell the asset, further exacerbating the price decline. This implies that while a speculative investment infuses new money into the market so long as prices are rising, it withdraws money from the market when prices fall. Thus, it constitutes a factor that amplifies price fluctuations and contributes to instability.

According to Minsky, the process that leads to a financial crisis (to be called a ‘bubble’ at this stage and defined later) stems from an external shock to the system sufficiently significant so as to cause at least one sector in the economy to believe that the economic future is positive. Private investors and firms operating in that business sector will take out loans in order to benefit from anticipated growth. These loans will finance what seem to be the most promising enterprises. As excess demand for those enterprises increases, their market value increases. This process may spur optimism into other sectors in the economy, sometimes to the point of generating euphoria.

What may be the nature of Minsky’s external shock? In the 19th century it was the success or failure of agricultural crops; in the 1920s it was the development of the car industry and establishment of infrastructures for transportation and industry; in the Japan of the 1980s it was financial liberalization and the rise in value of the Japanese yen; in the second half of the 1990s, it was, globally, the development of the Internet, which ensured (or so people thought) improved profitability of firms to the point of creating a ‘new economy’. In other instances it was the start or end of a war.

As one may gather, the causes might be different but the outcome is similar. Time and time again, investors, manufacturers and speculators convince themselves that ‘this time is different’. That notion, a repeated and central motif in the long history of financial crises, delivers the sad fact that many of the lessons taught are not learned. And even if they are learned in academic circles, they are not assimilated into the investment community. ‘This time is different’ is a phrase that Sir John Templeton named ‘the four most expensive words in the English language’.

1.3 Bubbles and Models of Bubbles

According to Minsky, financial crises begin with an external shock that results in a bubble; what has not been discussed, however, is why bubbles grow to the proportions that only in retrospect appear insensible. When and why do they collapse, and, generally speaking, how do we define a bubble?

Charles Kindleberger,2 an important researcher into financial crises, attributes a socio-psychological explanation of a bubble’s development in Minsky’s model: He contends that private investors and firms who see their neighbors profiting from speculative investments find it hard to remain indifferent, so they too enter the circle of speculators.

Kindleberger coined the expression: ‘There is nothing as disturbing to one’s well-being and judgment as to see a friend get rich.’ In the same vein, banks, too, cannot stand still and watch their competitors increase their market share and profits; therefore they increase loans to interested borrowers, lessen their quality control and expose themselves to increased risk. Thereafter, households and businesses, regularly not part of the circle of speculators, can be swept away into a bubble-producing circle that feeds itself so long as prices rise. Suddenly it seems as if it’s exceedingly easy to get rich and risk is perceived as being especially low. If someone acknowledges they are invested in a bubble asset, they are in many cases convinced that they’ll be able to sell before the big crash. This is also how numerous other players think, but in the meantime no one is selling because prices keep increasing.

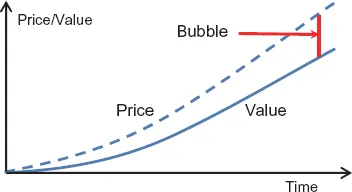

Kindleberger calls this process ‘mania’ or a ‘bubble’. ‘Mania’ is a word that alludes to irrational behavior while ‘bubble’ hints at something destined to burst. There are numerous definitions for a bubble, but it seems that most economists would agree on one: a deviation of an asset’s market price from its fundamental, basic value. In other words, the size of a bubble is measured by the difference between the asset’s market price and its fundamental value, as presented in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Price, value, and bubble

While an asset’s price can be easily observed in the market, its fundamental value cannot be directly observed, but instead is calculated by an economic model. The economic model takes into account anticipated cash flow, risk, liquidity and other factors. Here lies the most problematic aspect of identifying and handling bubbles: Because there is no single agreed-upon model that investors and economists use in evaluating an asset’s fundamental value, different analysts will arrive at different values. Therefore, they might not agree on the presence and size of a bubble. A situation may arise in which one analyst concludes that a bubble exists while their colleague, employing a different model may conclude the opposite. The colleague might even employ the same model but make different assumptions regarding the magnitude of specific parameters within that model and conclude that no bubble exists.

Many models attempt to explain bubbles. Most can be segmented into two major categories: rational and behavioral.3 Rational models can further be segmented into two subcategories. Firstly, ‘symmetric information’ models where all investors have equal access to information, Secondly, ‘asymmetric information’ models are those based on differential access to information.

Behavioral bubble models can also be divided into two major categories: ‘heterogeneous beliefs’ vs. ‘limits of arbitrage’. The next four subsections provide more detail on these subcategories.

1.3.1 Rational models: Symmetric information

There seems to be agreement among researchers that bubbles cannot evolve in an economy in which prices are determined by rational investors operating in an efficient market4 under information symmetry, except under very odd conditions. A key reason is ‘backward induction’, which says that if indeed investors have perfect knowledge of the economy, they must know that a bubble exists, therefore the ‘price’ must at some point drop to close the gap with the asset’s ‘value’. But if this drop is expected, say 30 days from today, all investors know that others will sell it beforehand, perhaps on the 29th day. Because everyone expects a massive sell-off on the 29th day, they will sell on the 28th day, and so on. The end game is that everyone sells the asset today, closing the gap and bursting the bubble immediately. Therefore, rational bubbles under symmetric information are generally ruled out.

1.3.2 Rational models: Asymmetric information

The general tone in an asymmetric information model is that not everyone in the economy is aware of the bubble, therefore it may prevail. To understand why, consider an extreme case where although everyone knows that a bubble exists, they are not certain about other people’s knowledge. Because people do not know for sure that everyone else knows that a bubble exists, they have an incentive to hold the overpriced asset. They do so because they are hoping to sell, for a profit, to ‘a greater fool’ (as Kindleberger put it) who is unaware of the bubble.

1.3.3 Behavioral models: Heterogeneous beliefs

In these models investors buy an asset because its price increased recently, ignoring its fundamental value. They make this peculiar purchasing decision because of one of the following behavioral patterns:5

| (1) | They may be overconfident in the signals they observe. Overconfidence stems from a number of reasons, among them the freedom to choose, familiarity with the situation, abundant information, emotional involvement and past successes. |

| (2) | If they held the asset before its price increased, and they buy more once it started increasing, they might attribute this good decision to their own judgment, rather than chance. This is called ‘self-attribution’. |

| (3) | They may buy the asset because of sentiment. |

Either way, rational investors sell the assets to behavioral investors, who end up losing on average. Because neither the rational nor the behavioral investors try to infer the other side’s beliefs from market prices, they ‘agree to disagree’ on the value of the asset, therefore hold heterogeneous beliefs.

1.3.4 Behavioral models: Limits of arbitrage

In these models irrational traders initiate a bubble by buying previously increasing stocks, similar to the behavior in the previous case. However, at the same time arbitrageurs are unable or have no incentive to trade against the bubble. One reason may be the high level of risk that behavioral investors impinge on the stock price. These unpredictable trades make arbitrage too risky, deterring arbitrageurs from attacking the bubble. Another explanation rests with the aversion to high risk that the suppliers of funds to arbitrageurs might exhibit as the bubble grows. A third explanation is that individual arbitrageurs know they cannot burst the bubble with their own funds, therefore they prefer riding it. While they also know that they can burst the bubble by collaborating with other arbitrageurs, they have no incentive to coordinate an attack.

Notice that in both types of behavioral method the investors lose money on average to the more systematic, rational arbitrageurs (professionals call it ‘dumb money’ vs. ‘smart money’). Economists who hold rational arguments maintain that over time either dumb money investors lose all their wealth to smart money investors, or dumb money investors deposit their funds with smart money managers. Either way, prices would eventually be determined by smart money investors, therefore behavioral factors should not have material effects at the aggregate level over the...