Chapter 1

Now and Then: The Species, Including Fossils

In creation stories of many northern native Americans, at the time of beginning and transformation, giant animals roamed the world and ate people.

The culture hero Saya of the Athapaskan-speaking “Beaver Indians” at the Peace River in British Columbia and Alberta took on, and transformed the giant, people-eating animals to their current size. Now the roles are reversed: people eat the animals.

The Amikwa on the north shore of Lake Huron have the Great Spirit Manitou shrink the giant animals to their present size.

R. Ridington, 1981

Comment: The sight of large bones of Pleistocene mammals might have spawned such narratives to link the past to the present. Ethnographers have also often invoked a “collective memory” stemming from times when giant animals coexisted with people.

Author

Living Beavers

The beaver is the second largest rodent after the South American capybara (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris). Beavers belong to the family Castoridae in the suborder Sciuromorpha of the order Rodentia. They are more closely related to squirrels and marmots than to mouselike rodents (Muridae). Beavers split from their closest living relatives 90–100 million years ago.1 For expediency, clever politicians have maneuvered the beaver into strange taxonomic neighborhoods. In 1760, the College of Physicians and the Faculty of Divinity in Paris permitted beaver meat on fasting days because the beaver’s scaly tail classified it as a fish and not a mammal! By the way, the beaver is not alone in this regard. The pope declared the similarly semiaquatic capybara of South America, the largest rodent in the world, a fish, when petitioned by Venezuelans and Colombians in the 16th century. So every year observant parishioners eat 400 tons of capybara during the fast of Lent.2

Two species of beaver live today: the North American Castor canadensis and Castor fiber in Eurasia. Efforts to find unequivocal genetic tests to distinguish the two species are continuing. Fused chromosomes, specifically monobrachial centric fusions of G-banded chromosomes, can be diagnostic.3 The North American beaver occurs from coast to coast and ranges from Alaska, Hudson Bay, and northern Labrador in the North to the U.S.-Mexico border, Gulf Coast, and Florida state line in the South (Fig. 1.1).

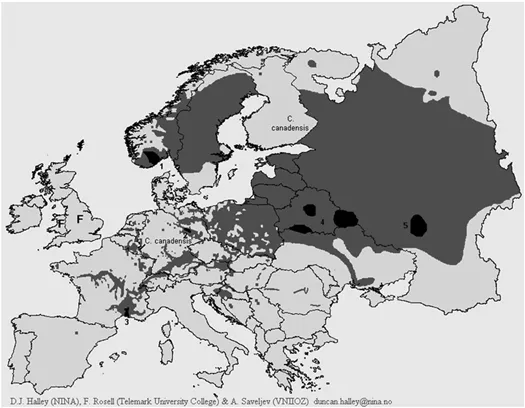

In the Old World, the beaver used to occur throughout Europe to the Mediterranean and far into northern Asia. In the early 20th century only about 1200 beavers remained in this vast area. In a spectacular comeback, by 2010 the numbers had increased nearly 900-fold! There are at least 1.05 million Eurasian beavers today. Beavers now populate most countries they formerly roamed in. In Europe, only southern countries lack them. These include Portugal, Italy, Greece, Albania, Bulgaria, Macedonia, Kosovo, and Montenegro.4 Figure 1.2 shows today’s distribution of Eurasian beavers in Europe, and Figure 1.3, for Russia and Asia.4 Chapter 18 deals with beaver populations in specific countries.

The North American beaver cuts almost all tree species and builds elaborate freestanding lodges. The like-sized Eurasian beaver, on the other hand, cuts mostly willow, even in mixed forest stands, and lives in bank burrows. For instance, along the Danube near Vienna, Austria, researchers found only one freestanding lodge; all others were bank lodges (J. Sieber, personal communication, 1982). The Eurasian beaver appears more ancient and conservative than its New World cousin, thought to be a younger and more progressive species.

Figure 1.1 | Geographical range of the North American beaver.

Figure 1.2 | Map of beaver distribution in Europe. Many isolated small populations have been coalescing by natural migration, and the process is continuing. The numbers 1–5 designate the five traditionally recognized subspecies of Castor fiber in Europe: 1 = C. f. fiber; 2 = C. f. albicus; 3 = C. f. galliae; 4 = C. f. belarusicus; 5 = C. f. osteuropaeus. Dark grey: current range of Castor fiber; black: relict populations of C. fiber; light grey: range of Castor canadensis in Europe, notably in Finland. Squares (e.g. Spain): reintroduction sites where beavers have not yet spread significantly. From: Halley, Rosell, and Saveljev, in press. Kindly supplied by Duncan Halley.

The two beaver species differ in their number of chromosomes: C. canadensis has 40 chromosomes (2n), and C. fiber has 48 (2n) (see Table 1.1).4 The two species can also be readily distinguished by alleles of the esterase-D locus (Es-d): on horizontal starch gel electrophoresis, the Eurasian beaver exhibits a fast-migrating allele, while the North American beaver has a slowly migrating allele.5

Figure 1.3 | Map of beaver distribution in Asia (Russia, Kazakhstan, Mongolia, and China). Dark grey: present range of Castor fiber; black: relict populations of C. fiber; light grey: range of C. canadensis in Finland is indicated. Numbers indicate traditionally recognized subspecies: 1 = C. fiber fiber; 6 = C. f. pohlei; 7 = C. f. tuvinicus; 8 = C. f. birulai. Kindly supplied by Duncan Halley.

Fossil Beavers

Enough fossils exist to illuminate the ancestry of modern beavers. The smallest extinct beavers were as large as a muskrat, and the largest reached 100 kg. Table 1.2 summarizes the sequence of beaver fossils found in North America and Eurasia.

Fossils show that beavers occurred from the early Oligocene to the Holocene in the New World, the late Oligocene to the Holocene in Europe, and the late Miocene to the Holocene in Asia.6 The first clear castorid was Palaeocastor from the Upper Oligocene of North America. The combination of swimming and exploitation of trees in a mammal probably appeared about 24 million years ago in the early Miocene.7 Tree exploitation evolved in high latitudes, possibly as adaptation to hard winters, as Rybczynski points out. In the middle and late Tertiary beavers were very numerous. It has been suggested that beavers of the Tertiary migrated between Eurasia and North America in both directions: Steneofiber from Eurasia to America, and Eucastor from the New World to the Old. The genus Castor may have migrated from Eurasia to North America during the Pliocene.

Beaver-gnawed wood occurs often in the fossil record. A former beaver pond from the early Pliocene on Ellesmere Island in the Canadian Arctic still contains beaver-cut branches and saplings and bears witness to the higher temperatures during that period.10 The plant and beetle remains in the accumulated peat tell of winter temperatures 15°C higher than today, and summer temperatures 10°C higher. The beaver pond deposits also contained remains of the first North American meline badger, Arctomeles. Other fossils included a shrew, a three-toed horse, a bear, a musk deer, and a wolverine.10 At the Ellesmere Island site, the beaver-gnawed sticks were found intertwined, suggesting some kind of “nest,” lodge, or dam.7

Table 1.1 | Some Differences between the Two Beaver Species

Dipoides from about 5 million years ago (late Pliocene) is thought to have given rise to Procastoroides. Procastoroides was first found in Nebraska and occurs in layers about 3 million years old. Procastoroides idahoensis, the “Idaho beaver,” about two thirds the size of Castoroides, in turn, is thought to be the ancestor of the giant Castoroides.

During the Pleistocene, the age of giant mammals, huge beavers such a Trogontherium in Europe, lived side by side with other colossal mammal species. It is anybody’s guess what their lodges must have looked like, if they built any. Trogontherium ranged from France to China.11 Castoroides ohioensis in North America was even larger. Recent calculations have refuted earlier claims that Castoroides was as large as a black bear. The earlier conclusion had been reached by extrapolating from the size relationships of skulls and femurs to body size in living beavers to those in fossil ones. Because the skull evolves in response to special needs, such as gnawing and chewing, it is a poor predictor for body mass. One obtains a different formula for the relationship between these measures and body mass by using the skull and femoral lengths of a broader taxonomic group, such as 19 rodent species.12 According to new modeling, the body mass of Castoroides was probably...