![]()

PART 1

THE POLICY FRAMEWORK REVISITED ANSWERING NEW CHALLENGES?

![]()

CHAPTER 1

SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY POLICY IN JAPAN

HIROSHI NAGANO1

1. Introduction

In Europe the conception that Japan is advanced in innovation seems to be somewhat prevalent. Perhaps, this view is not a myth because I found such indications in the European Innovation Scoreboard published by European Commission. However, in Japan people have gotten accustomed to the notion that Japan is lacking capabilities in innovation, since we are always shown annual statistics such as that presented by IMD (Institute for Management Development in Switzerland), indicating Japan’s declining position in competitiveness.

Japanese people have recognized this since the burst of the economic bubble in 1991. Since then, a depression-like feeling caused by the economic stagnation has continued to exist in Japan. People have always been keen on finding reasons for the stagnation, which can be attributed to the decrease of economic productivity in the 1990s. One explanation may be that though Japan has accomplished the so-called catch-up phase of economic development, it has since been struggling to get accustomed to behave as a member of world leaders. This implies that there may be hurdles which must be overcome by new economies to competitively penetrate into existing top-notch powers.

The new ruling party in Japan which beat the 50 years’ reign of the previous government of the Liberal Democratic Party in summer 2009 gave at first the rosy expectation for science and technology arena. The Premier, Dr Hatoyama, is actually the first Prime Minister to have graduated with a degree in the science and technology discipline and the first Premiere in Japan to hold a PhD. Moreover, Vice-Premiere and Finance Minister, Mr Kan, Chief Cabinet Secretary, Mr Hirano, and Minister of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Mr Kawabata, who is concurrently in charge of Science and Technology Policy in the Cabinet Office, all hold degrees in the field of science and technology. This may be coincidental, but it is quite unique in Japan, where most of the people who govern the country have an educational background in law. Accordingly, people in the field of science and technology expected much sympathy from them.

On the contrary, the newly established Government Revitalization Unit recommended budget cuts for many research initiatives. Even Nobel Prize laureates lamented new government’s lack of appreciation for science and technology. However, I feel that this event spotlighted also the lack of good basis of communication with the public in terms of science and technology policy, and I hope that this incident would contribute to improving science communication among scientists, government, and the people.

In this paper, I would discuss the development of the recent science and technology policy in Japan and its implication for the future.

2. Science and Technology Basic Plan

The role of the government, as the main provider of public resources, is to set out a suitable framework to facilitate a variety of people to do their activities, for instance, carrying out research activities for the sake of sustainable development of society. It should cover a variety of issues and fields from the creation of knowledge to the creation of innovation-oriented market. Since long, the Japanese government laid emphasis on the promotion of science and technology. However, the year 1990 was a turning point. This year is mainly memorized among us as the end of the Cold War. At the same time it brought the change of the geopolitical position of Japan and for the whole world it was the real start of the globalization. After the burst of the economic bubble in 1991 in Japan, the R&D investment of Japanese industry consecutively decreased for three years from 1992. This phenomenon struck many people, including parliamentarians and led to the enactment of the Science and Technology Basic Law.

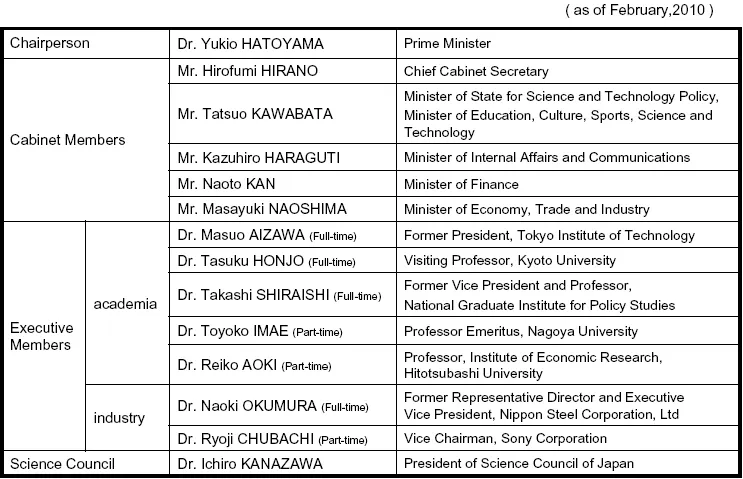

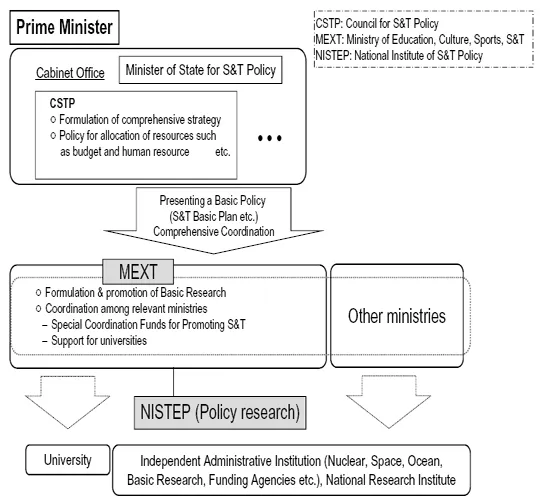

The Science and Technology Basic Law stipulates that the government shall prepare and implement Science and Technology Basic Plans. The First Basic Plan was adopted in July 1996 by the cabinet and covered the period 1996–2000. Subsequently, two more Basic Plans had been adopted for the 2001–2005 and 2006–2010 periods, respectively. The organizational and other circumstances under which the Basic Plans have been produced and implemented have differed considerably. The First Basic Plan was drafted by the former Science and Technology Agency (STA) and the Council for Science and Technology (CST) of the Prime Minister’s Office and was presented less than seven months after the Science and Technology Basic Law had been enacted. While the First Basic Plan mainly dealt with systemic issues, the Second Basic Plan added priorities expressed in terms of specific scientific and technical fields. A new Council for Science and Technology Policy (CSTP) started its activities in January 2001, only three months before the beginning of the Second Basic Plan. Therefore, most of the preparatory work was also done by STA and CST. STA was merged with the Ministry of Education, Sports and Science to form the new Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) from April 2001. The CST was significantly upgraded into a supreme advisory body, CSTP, with greater authority. The present CSTP has 14 members, six of whom are members of the Cabinet (Fig. 1.1). Four of the noncabinet members work full time for the CSTP, while for the remaining four noncabinet members of the CSTP is a part-time activity. The President of the Science Council of Japan, which represents the scientific community, is an ex officio member of CSTP. On the whole, an effective framework for policy coordination was established, with CSTP playing a leading role. The CSTP is located within the Cabinet Office and expected to suggest national strategies as the chief controller of the promotion of policies. Its function is mainly the formulation of comprehensive strategy and proposing policies for allocation of resources such as budget and human resources (Fig. 1.2). In September 2001, CSTP decided on promotion strategies for four priority fields (life sciences, ICT, nanotechnology and materials, and environment) and four additional fields (energy, manufacturing, societal infrastructure, and frontiers), which had been stipulated in the Second Basic Plan.

Figure 1.1: CSTP members.

Figure 1.2: Governmental structure for science and technology.

The preparation of the Third Basic Plan was done by the CSTP from the very beginning. It was preceded upon a comprehensive review of government science and technology policy, including the first three years of the Second Basic Plan, which was made public in May 2004 by the National Institute of Science and Technology Policy. The concept of the Third Basic Plan consists of three ideas and two policy goals per each idea, altogether six policy goals. The first idea is to create human wisdom, the second idea is to maximize national potential, and the third is to protect nation’s health and security. Two policy goals per each idea are as follows:

• “Idea 1” Create human wisdom — to realize a nation contributing to the world by creation and utilization of scientific knowledge

o Goal 1: Quantum jump in knowledge, discovery and creation — accumulation and creation of diverse knowledge to ensure a bright future

o Goal 2: Breakthrough in advanced science and technology — efforts for human dreams to become true

• “Idea 2” Maximize national potential — to create a competitive nation achieving sustainable growth

o Goal 3: Economic growth and environmental protection — achieving sustainable economic growth based on environmental protection

o Goal 4: Innovator Japan — realizing a strong economy and industries creating innovation constantly

• “Idea 3” Protect nation’s health and security — to become a nation that secures safety and quality of life

o Goal 5: Nation’s good health over lifetime o Goal 6: The world’s safest country

As described, these Basic Plans cover comprehensive fields from system reforms to priority settings. Increasing competitive research funds and support plan for many young researchers are some examples of accomplished items. To realize these goals, certain amount of the prospective government investment is described in the Basic Plans. In case of the first Basic Plan it was 17 trillion yen, in the second Plan 24 trillion yen and finally in the third Basic Plan 25 trillion yen. In case of the first Basic Plan it was actually realized, but in the latter cases, they were not attained. However, this indication expresses a strong will of the government, as there are no similar notations in other medium-term programs of the government nowadays, not even in the Defense Framework Program, because of the government’s financial situation.

3. Science and Technology-Related Budget and the Flow of R&D Expenditures in Japan

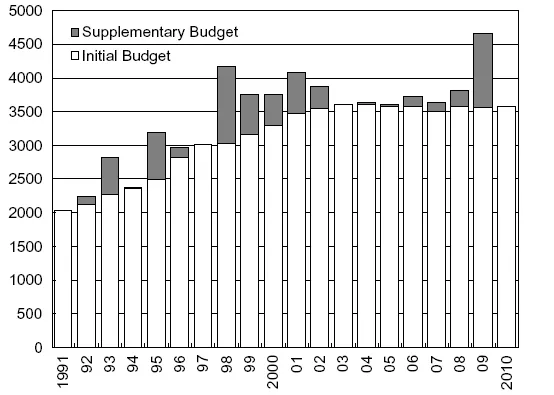

The development of science and technology-related budgets of the government including the initial and supplementary budgets are to be seen in Fig. 1.3. During the 1990s, the initial science and technology-related budget grew steadily. Since the beginning of the 21st century, the initial budget has stayed more or less unchanged. In general, supplementary budgets play an important role. This was particularly true during 1990s when the Japanese economy was stagnant and the government tried to reactivate it. In recent years, the top priority of the government became a rebalancing of annual budgets. Nevertheless, science and technology area was not severely affected in comparison to other areas, although it was not raised.

Figure 1.3: Budget appropriation for science and technology.

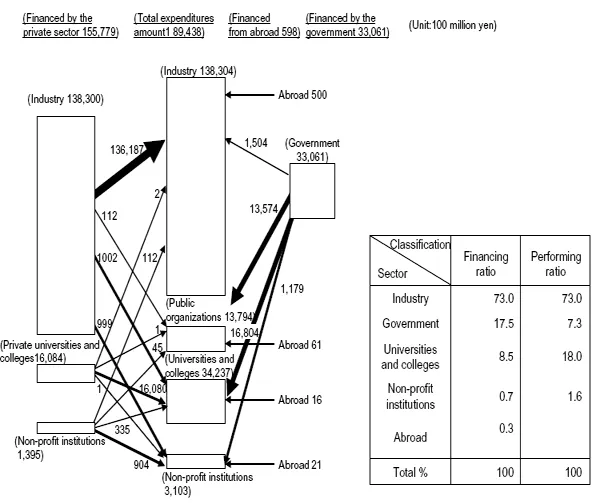

The most remarkable feature in the flow of R&D expenditures in Japan is that industry’s funding share accounts for ca. 73% of the whole R&D expenditures in FY 2007 (France 52.4%, FY 2006). Partially it is because of the low investment in S&T from the government, but this surely implies the willingness of the industry for investing in R&D. The flow chart of the R&D expenditure in Japan illustrates interesting points, such as: (1) The government invests less than 18% (France 38.4%); (2) There is almost no crossover funding between public and private sector; (3) Private universities and colleges, meaning mainly the tuition fee of their students, bear more than 8% of the country’s total R&D expenditures; and (4) Flow of R&D expenditures from abroad is almost zero. This clearly illustrates strength and weakness of Japanese R&D system (Fig. 1.4).

Figure 1.4: Flow of R&D expenditures in Japan (FY 2007).

Source: Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. “Report on the Survey of Research and Development”.

4. Priority Setting

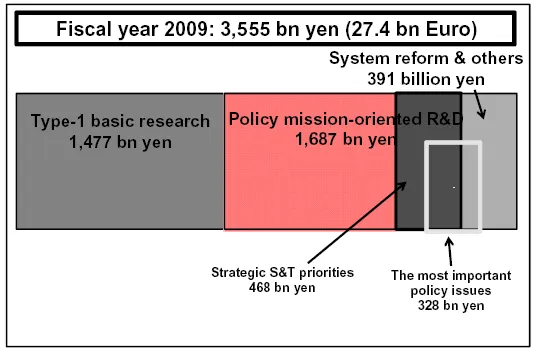

Main components of the initial FY 2009 Government budget for science and technology is described in Fig. 1.5. The big portion (42%) is categorized as “Type-1 basic research.” According to the present Third Basic Plan,

Basic research consists of two types: Type-1 basic research that is conducted based on the free ideas of researchers in Science and Technology, including human and social sciences; and Type-2 basic research that aims at future applications based on policies.

This part is devoted mainly for block funding of national universities, together with competitive research grants for academic researchers, and not considered appropriate for prioritization.

The biggest portion (47%) is categorized as “Policy mission-oriented R&D.” At the time of the Second Basic Plan, the prioritization of R&D was first introduced and the following fields were designated; as four Priority Fields: (1) Life sciences; (2) Information and telecommunications; (3) Environmental sciences; and (4) Nanotechnology and materials science/technology. Subsequently, four additional Promotion Fields were designated: (1) Energy; (2) Manufacturing technology; (3) Infrastructure; and (4) Frontier (outer space and the oceans). However, these fields were then considered rather vague and broad. Consequently, in the present Third Basic Plan, although the previous prioritization remained untouched, a new set of Strategic Science and Technology priorities were designated irrespective of prioritized fields selected, for instance, “Science and technology for reconstructing program of life”; “Development of a world-leading Next Generation Super Computer”; “Ocean and Earth Observation System”; “Advanced materials and process technology that can play a key role for bringing about innovation”; “Urban systems technologies which realize a drastic reduction in energy use by wide-area use of energy”; “Science-based manufacturing visualization technology”; “Land monitoring and management technology for disaster mitigation” and so on. On top of that, CSTP recently introduced the concept of “the most important policy issues” which spotlighted specific areas of urgent needs, covering both the R&D fields and system reform. These are specifically as follows: (1) Transformative Technologies; (2) Low-carbon Technology; (3) Science and Technology Diplomacy; (4) Regional Empowerment through Science and Technology; and (5) Pioneering Projects for Accelerating Social Return. This somehow implies the change of prioritization policy without changing the Basic Plan itself.

Figure 1.5: Main components of the fiscal year 2009 Government Science and Technology Related Budget in Japan.

Source : CSTP (Regarding Overview of the FY 2009 S&T-related Budget Proposal, 20 Feb. 2009) Graph modified by Lennart Stenberg & Hiroshi Nagano.

5. Importance of Innovation

It is often said that innovation is a key to becoming a member of the outstanding countries in the world, leading to my inquiry of the existence of innovation in Japan. Assuming “innovation” as the introduction of new things, ideas, or ways of doing something into the market, people may consider as examples of innovation such items as motor-bicycles (Honda, etc.), automobiles (Toyota, etc.), transistor-radios, walkman (Sony, etc.), facsimiles and copy-machines (Ricoh, Canon, etc.), video-tape recorders (JVC), and so on. Innovation in conventional industries such as the iron industry is apparent as today’s au...