![]()

CHAPTER 1

TRADITIONAL MEDICINES

1.1Primitive and Archaic Medicines

We do not know what primitive men thought or did about their health problems, beyond what little the study of their fossil remains and the accompanying artifacts may suggest. For example, we know that many primitives knew how to suture wounds and set broken bones, and that some of them practiced trephination. However, we do not know why they did the latter: whether to treat migraines or to release evil spirits.

By contrast, anthropologists have found out something about the ideas and practices of modern primitives. For example, the Amazonian Indians, who are among the most backward, use several plants to which they attrib¬ute healing or magic properties. Some tribes believe that they protect children from evil spirits by rubbing them with some plants. Others eat plants that, although poor in nutrition, are appreciated for their shape, color, or some other trait. This usage is enshrined in the doctrine of signatures, popular in Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, according to which certain plants cure diseased organs because they resemble them in shape. And as recently as in the 1960s, Che Guevara, the physician turned revolutionary, was amazed to learn that his Congolese comrades believed that a certain magic potion had made them invulnerable to the colonialists’ bullets.

A philosopher may think that the Amazonian tribesmen are dualists, in the sense that, while their practices are materialistic, their explanations are spiritualistic. Perhaps he will add that the Amazonians are half empiricists and half apriorists — the former because they learned their practices by trial and error, and the latter because other practices owe nothing to experience. For example, frequent bathing is an effective prophylactic habit, whereas tribal mutilations, deformations, and scarifications are harmful, as is the insertion of thorns or bones in the skin.

We also know something about the medical beliefs and practices prevailing in the earlier civilizations, partly because some of them persist in ours. Despite their marked differences, all of them shared the belief that some or all diseases were caused by gods, evil spirits, or witchcraft (Trigger 2003: 620). Hence, sacrifices to supernatural entities were thought to help the application of natural remedies.

But in daily matters, it was always considered advisable to take practical measures, for the gods might be bribed and, in any event, they were busy with cosmic affairs. So, in practice, the sick person in the ancient world paid two fees: to his healer and to the god in charge of his particular disease. This was the ruling medical practice in all the early civilizations, whether in Eurasia, Africa, or America — a mixture of religious ceremony with more or less successful empirical practices (see, e.g., Mata Pinzón 2009; Sigerist 1961; Valdizán 2005; Varma 2011).

The Hippocratic, Ayurvedic, and traditional Chinese medicines, which had already peaked two millennia ago, stand out. They were the most important medical legacy of antiqutity because, though unscientific by modern standards, they broke with the magico-religious tradition; they were thoroughly secular and even materialist rather than spiritualist. Moreover, all three contained some nuggets of true knowledge and a few efficient practices, particularly concerning prophylaxis, diet, and lifestyle.

In the West, the Hippocratic school is the best known of all the traditional medical traditions. We owe to it the thesis that diseases are natural processes beyond the reach of the gods; that the disease of every kind has its own peculiar course; that most disorders heal without intervention; and that to keep well, as well as to recover health, we must observe certain simple hygienic rules, such as eating and drinking in moderation. We also owe the same school the attempt to find general laws and rules — an attitude common to all the sages of ancient Greece.

The ancient Egyptians had a lot of special mathematical and medical knowledge, but they did not bequeath us a single general theorem or general medical rule. In particular, the famous Edwin Smith papyrus from 1,500 B.C. contains studies of 48 wounds in various parts of the body. The descriptions of the wounds and their treatments were detailed, objective, and rational. But they do not suggest any generalizations; they are strictly empirical, in contrast with the official ideology, which worshipped one god for every one of the 200 known diseases.

Empiricism is of course the sticking to experience and the corresponding rejection of magic and religious ideas. The same philosophy inspired also radical skepticism about theorizing, as exemplifed by the brilliant if destructive Sextus Empiricus. Radical skepticism was certainly reasonable at a time when almost all the extant theories were false or, as in the case of Aristotle’s, they contained some religious ingredients.

Skepticism about scientific theories ceased to be reasonable and progressive when David Hume embraced it at the beginning of the eighteenth century, when classical mechanics was flourishing and the earliest biological and medical hypotheses emerged. Hume, an implacable critic of religion, also rejected Newtonian mechanics because it contained concepts, such as that of mass, that go beyond phenomena (appearances).

(This phenomenalism of Hume and his followers, from Immanuel Kant to Auguste Comte to Ernst Mach to Pierre Duhem to the logical positivists of around 1930, overlooked, opposed, or distorted all of the deep scientific theories, every one of which involves concepts referring to imperceptible entities and processes, from atoms and force fields to evolution and the innards of stars. Kant was well aware that phenomenalism is anthropocentric, but he was wrong in claiming that its adoption was “a Copernican revolution,” for in fact it was a counter-revolution. Pierre Duhem realized this when he launched his attack on Galileo, whom he called “the Florentine mechanic,” and proposed his own “physics of a believer.”)

From the time of the consolidation of the scientific attitude, around 1800, empiricism was frankly regressive; it opposed all the bold new scientific theories, such as electrodynamics, atomism, and astrophysics, and it slowed down the renewal of medicine on the basis of chemistry, pharmacology, and biology. From then on, the philosophy that best favors the search for factual truth is what may be called ratioempiricism, which proposes a synthesis of reason with experience, as practiced in the experimental trial of medical hypotheses, such as those of the existence of oncogenes and of strong ties between the immune system and the rest of the body. However, let us go back to antiquity.

The transition from shamanism to Hippocratic medicine was slow and had an intermediate phase: the secular, rationalist, and materialist speculations of Thales, Empedocles, Anaxagoras, Democritus, Epicurus, and other pre-Socratics. These great thinkers speculated boldly, but they also argued and rejected the recourse to the magico-religious. Of course, the “elements” they imagined (water, air, soil, and fire) turned out to be complex, not elementary, and we now know that atoms do not move incessantly in a straight line. But we grant that the enormous variety of things around us comes from combinations of atoms of only 100 species, and that these constituents are material, not spiritual, as a consequence of which they are studied by physics and chemistry, not theology.

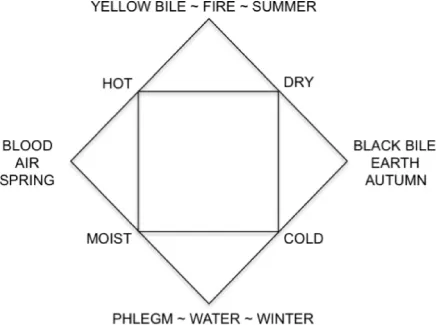

We all admire the great achievements of the Hippocratic school, but we must discard nearly all their explanations for, although they were rational and materialist, they were also speculative. In fact, the nucleus of the Hippocratic conception of disease is the hypothesis of the equilibrium of the four humors: blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile. (The black bile, or melaina chole, has not been identified. It has been conjectured that it was an invention designed to satisfy the school’s love of the number 4, which would also be the number of “elements.”) Sickness would come from an imbalance of humors, which the medic has to correct. For example, if he suspects that there is an accumulation of blood in the feet, he will bleed them. (It would take two millennia to discover that blood circulates.)

Since not all humors are concentrated, neither are their disequilibria. This is why the humoral pathology is holistic. Therefore, so are the corresponding therapy and prophylaxis: the Hippocratic medic treated his patient as a whole. He prescribed global treatments: hygiene, diet, and lifestyle. This may have been the most lasting contribution of archaic Greek medicine: recommending good preventive habits.

Their holism did not prevent Hippocratic doctors from speculating about the functions of the few organs they distinguished. For example, Hippocrates adopted the hypothesis of the Sicilian medic Alcmaeon, that the brain is the organ of the mind, whereas the ancient Egyptians believed that the function of the brain is to secrete mucus, and Aristotle believed that its role was to cool down the blood, and the ancient Chinese held that the spleen is the organ of the mind.

Alcmaeon and Hippocrates were then the forerunners of biological psychology and psychiatry, the alternative to their magico-spiritualist, idealist, and dualist counterparts. They also inspired the popular classing of personalities (or temperaments or constitutional types) into phlegmatic, sanguine, and bilious.

With hindsight, it is easy to ridicule the humoral pathology. But it was the first to try and explain symptoms by proposing a concrete mechanism that involved only material entities, the four humors, three of which were familiar. Besides, this medical hypothesis, unlike the others, was not isolated but was part of a whole worldview that included another three quartets: Empedocles’ four elements, the states warm–cold–dry–humid, and the four seasons. Those four constituents reinforced one another, which helps explain the popularity of Hippocratic medicine during two mllennia. (See Figure 1.1.)

The Ayurvedic and traditional Chinese medicines too were centered in equilibrium ideas. Three millennia ago, the Vedas postulated that every disease consists in an imbalance among three bodily systems — vayu, pitta, and kapha — which they did not bother to describe. Note their preference for the number 3, whereas the Greeks favored 4, the Mesopotamians 7, and the Chinese 2 and 5.

Fig. 1.1. The humoral pathology was part of a four-part cosmology (redrawn from Sigerist 1961, p. 323 ).

In all these cases, the medical theory fit the ruling worldview. But in the case of the Ayurvedics, this adjustment was only partial, as it ignored the tens of thousands of Hindu gods. And the corresponding therapy worked only with material means, such as salves and herbal teas, while the sacred scripture held that the universe is spiritual, whereas everything material is illusory. Nor is such duality rare or surprising: life must go on while paying the gods their due.

The followers of traditional Chinese medicine — just like the Ayurvedics and the Hippocratics — sought harmony. In their case, the desirable balance was that between the Yin and the Yang — an idea that agreed with Confucius’ political principle of seeking social harmony. Those alleged basic properties were named but not described with any precision, and consequently they lent themselves to arbitrary interpreta-tion. The same holds for the Qi (or chi ), usually translated as “life force or energy,” and is assumed to flow along the “meridians” or canals. These alleged anatomical entities are carefully drawn in the anatomic Chinese atlases produced for the past two millennia, but no modern anatomist has found them, and no physiologist has ever detected the Qi said to flow along them.

Suppose we are seen by a traditional Chinese doctor. What will he do to find out what ails us? He will examine our body, in particular the tongue and hands, in search of visible signs. He will put special attention to the shape and color of the tongue. If it is pale and swollen, and with a thick white coating, the diagnosis will be “Yang deficiency”; a red and cracked tongue will indicate “Yin deficiency”; and a pale and deformed tongue with teeth marks will be clear evidence that the patient is lacking in Qi. In turn, Yang deficiency indicates feeling cold and back pain; Yin deficiency indicates hot flashes and insomnia; and Qi deficiency points to fatigue and worry. Nothing seems to point to any of the most common infections or chronic diseases; it’s all instant diagnosis of conditions one can live with.

Don’t ask the traditional Chinese doctor what Yang, Yi, or Qi are, nor why Qi flows only along the “meridians”; nor what may obstruct the Qi flow, nor about the mechanism whereby a needle inserted in the right place will restore it. What matters is that the healer is sure that the said excesses or deficiencies occur and will be easily corrected by sticking needles at places invented two millennia ago, or by sipping infusions of certain herbs of unknown composition. He won’t offer evidence of any sort, nor could he, given that he does not know what Yang, Yin, or Qi are, nor how they could be experimentally wiggled and measured. The traditional Chinese medic does not expect his patients to ask such ques-tions, any more than a Christian priest expects his parishioners to ask him for evidence for resurrection. Both rely on the gullibility of their clients, who have been educated to believe without evidence and without explanation. There is no discovery in all that because there is no research — hence no research fraud. But at least traditional Chinese medicine is naturalistic rather than either shamanist or religious.

Chinese traditional medicine handles the human being as if he were an inscrutable black box with buttons and color lamps, and it treats its practitioner as a robot whose task it is to press buttons as indicated by a tradition-given code that pairs off colors with buttons. (This code is part of the Yellow Emperor’s Inner Laws, the canon of the lore, composed between four and two centuries B.C.) Neither medic nor patient knows the nature of the sickness or the treatment. By contrast, scientific medicine and its prac-titioners look like translucent (or semitransparent) boxes: in principle everything can be examined, analyzed, tried out, and discussed. And no medical treatise is expected to be unalterable. Moreover, every day there is a medical novelty announced in the specialized journals, and consequently a significant part of the knowledge of today’s medical graduate is expected to become obsolete in just five years from now.

In any event, since the traditional Chinese medic conceived of disease as an imbalance between the Yin and the Yang, his task consisted in guessing the said imbalances from symptoms, and in restoring the former — a task he attempted to carry out by performing acupuncture and prescribing massage, and diets including medicinal teas — of which there were more than 10,000 kinds. In this regard, in resorting exclusively to material means, the traditional Chinese medic was far superior to the shaman or priest. But in both cases what really worked, when it did, was presumably a placebo. Only experiment could say what, if anything, really worked. But experiment was invented two millennia after Chinese medicine was invented, and its contemporary practitioners do not experiment. (See Chapter 7.)

1.2Achievements and Failures of Traditional Medicine

The above-mentioned hypotheses on balance or harmony are so imprecise, that they are untestable, hence unscientific. However, some of them can be refined and become the subject of experimental test. In particular, the modern version of the idea of bodily balance is the physiological concept of homeostasis, the constancy of the milieu intérieur that Claude Bernard conceived two millennia later, and Walter Cannon refined a century after Bernard.

One century after Bernard, it was found that the said balance results from negative feedback mechanisms. For example, the skin temperature is regulated by the hypothalamus, and the heart rhythm by the medulla oblongata. The search for bodily mechanisms is beyond traditional medicine, which at most delivered correct but superficial descriptions of overall processes, such as digestion.

Traditional medicine claimed to describe and explain all the known diseases (only modern medicine admits limitations). But it was unable to accomplish this task for lack of the biological knowledge required to correctly explain either the origin or the course of any disease. In sum, ancient medicine was nearly impotent because it was prescientific.

One might say that, contrary to Hippocrates’ expectant and prudent attitude, the contemporary internal physician seeks to maintain or restore the normal values of the parameters that characterize the internal milieu of the healthy organism, such as temperature, blood pressure, acidity, and sugar and cortisol levels — all of them measurable and alterable by various means. (Incidentally, homeostasis, or “the wisdom of the body,” as Cannon famously called it, goes only so far: sometimes the immune system “goes haywire,” as is the case with the autoimmune disorders, from diabetes to AIDS.)

Besides, the ancient conjectures about bodily equilibrium, though imprecise and speculative, are materialistic, so that their advent was an enormo...