![]()

Part I

FROM ADAM SMITH TO MICHAEL PORTER

![]()

1

TRADITIONAL MODEL: THEORY

SUMMARY AND KEY POINTS

Mercantilism viewed trade as a zero-sum game in which a trade surplus of one country is offset by a trade deficit of another country. In contrast, Adam Smith viewed trade as a positive-sum game in which all trading partners can benefit if countries specialize in the production of goods in which they have absolute advantages. Ricardo extended absolute advantage theory to comparative advantage theory. According to Ricardo, even if a country does not have an absolute advantage in any good, this country and other countries would still benefit from international trade. However, Ricardo did not satisfactorily explain why comparative advantages are different between countries. Heckscher and Ohlin explained that comparative advantage arises from differences in factor endowments. This theory appears to be virtually self-evident. However, Leontief found a paradoxical result.

Some economists have developed alternative theories because the Heckscher—Ohlin model did not work well in the real world. These theories include product cycle, country similarity, and trade based on economies of scale. There are many other theories. However, the purpose of this chapter is not to extensively review the economic theories but to provide background knowledge for understanding the evolution of competitiveness theory. Notwithstanding, all of the theories discussed in this chapter are still useful to some extent in understanding today's industrial and trade policies. They are also helpful in evaluating the debate over competitiveness in Chapter 2, which is an initial step to the understanding of a new comprehensive approach of this book.

MERCANTILISM

In 1492 Columbus reached the New World; in 1501, Amerigo Vespucci discovered the mainland of the continent; and in 1519 Magellan reached the Philippines around the southern tip of South America and opened the Western route to India. These discoveries were possible because of scientific development in the areas such as astronomy and shipbuilding. Merchants and traders wanted to expand their business to the East because trading Eastern and Western products was profitable. International business became important in the age of discovery and exploration during the 15th century.

An economic theory at this time was called mercantilism. It continued to be the dominant economic thought until the 18th century. The mercantilists thought of wealth as gold and silver, or treasure, a term common at that time. The policy of accumulating precious metals was called bullionism. In the earliest period, bullionist philosophy translated into encouraging imports and forbidding exports of bullion. This policy soon shifted toward regulating international trade to achieve a favorable balance of trade. Mercantilism emphasized the necessity of a country to acquire an abundance of precious metals. To do this, the country had to export the maximum of its own manufactures and to import the minimum from other countries. The excess of exports over imports would be paid for in gold and silver.

The policy then shifted toward encouraging domestic production. The rationale was that the country, producing more goods for export, could achieve a favorable balance of trade and thus a bullion inflow. This policy was well explained by Thomas Mun (1571–1641), a director of the East India Company and a principal mercantile theorist. His main contention was that to increase the wealth of the nation, England must sell to other countries more than she bought from them. He advised his people to cultivate unused lands; reduce the consumption of foreign wares; be frugal in the use of natural resources, saving them as much as possible for export; and develop industries at home to supply necessities. These are the tenets of the thrifty businessman. However, these are not only the responsibility of individual merchants. The government should also have an obligation. It could thus be advised for the government to prohibit imports and subsidize exports.

At this time a tax policy was important. The country could achieve mercantilist goals by lowering taxes for exports and imposing high tariffs on imports. However, taxes were often superimposed on the areas which were not directly related to trade. For example, in England, there were even taxes on windows, births, burials, marriages, and bachelors. In addition, high tariffs on imported items caused the smuggling industry to thrive. Another important policy was to grant monopoly for certain important sectors such as glass manufacturing, paper manufacturing, and copper mining. However, this policy was also abused frequently and became less helpful to the industrial structure.

ABSOLUTE ADVANTAGE

The major problem with mercantilism was that it viewed trade as a zero-sum game in which a trade surplus of one country is offset by a trade deficit of another country. In contrast, Adam Smith viewed trade as a positive-sum game in which all trading partners can benefit. A large part of The Wealth of Nations (Smith, 1776) was devoted to an attack upon mercantilism. Smith believed in the operation of natural law, or invisible hand, and thus favored individualism and free trade. Smith said that each man is more understanding than any other as to his own needs and desires. If each man were allowed to seek his own welfare, he would in the long run contribute most to the common good. Natural law, rather than government restraint, would serve to prevent abuses of this freedom. Specifically, the advantage of this natural law in Smith's eyes came from the division of labor. Smith explained this with the example of a pin factory:

To take an example,… the pin-maker; a workman not educated to this business, not acquainted with the use of the machinery employed in it, could make one pin in a day, and certainly could not make twenty. But in the way in which this business is divided into a number of branches, One man draws out the wire, another straights it, a third cuts it, a fourth points it, a fifth grinds it at the top for receiving the head; to make the head requires two or three distinct operations; to put it on, is a peculiar business, to whiten the pins is another; it is even a trade by itself to put them into the paper; and the important business of making a pin is, in this manner, divided into about eighteen distinct operations, which, in some manufactories, are all performed by distinct hands, though in others the same man will sometimes perform two or three of them. I have seen a small manufactory of this kind where ten men were employed…. Those ten persons could make 48,000 pins in a day. Each person, therefore, making a tenth part, might be considered as making 4,800 pins in a day. But if they had all wrought separately and independently, they certainly could not each of them have made twenty, perhaps not one pin in a day…

(Smith, 1776, p. 10)

Smith extended this idea of “division of labor” to that of “international division of labor.” Now consider how much more production there would be if countries specialized in production just as the pin-makers did in his example. Specialization, cooperation, and exchange were responsible for the world's economic progress, and therein lay the road to future achievements. International trade was thus a positive game to Smith. In practice, however,Smith saw various barriers set by governments that restricted the free flow of international trade. His famous passage is as follows:

It is the maxim of every prudent master of a family, never to attempt to make at home what it will cost him more to make than to buy. The taylor does not attempt to make his own shoes, but buys them of the shoemaker. The shoemaker does not attempt to make his own clothes, but employs a taylor. The farmer attempts to make neither the one nor the other, but employs those different artificers…."

“What is prudence in the conduct of every private family, can scarce be folly in that of a great kingdom. If a foreign country can supply us with a commodity cheaper than we ourselves can make it, better buy it of them with some part of the produce of our own industry, employed in a way in which we have some advantage….“

“The natural advantages which one country has over another in producing particular commodities are sometimes so great, that it is acknowledged by all the world to be in vain to struggle with them. By means of glasses, hotbeds, and hotwalls, very good grapes can be raised in Scotland, and verygood wine too can be made of them at about thirty times the expence for which at least equally good can be brought from foreign countries. Would it be a reasonable law to prohibit the importation of all foreign wines, merely to encourage the making of claret and burgundy in Scotland?

(Smith, 1776, p. 336-338)

In criticizing mercantilism, Smith showed how all forms of government interference, such as granting monopolies, subsidizing exports, restricting imports, and regulating wages, hampered the natural growth of economic activity. In contrast, Smith argued the advantages of specialization by regions and nations. Beginning with such reasoning, Smith showed how each nation would be far better off economically by concentrating on what it could do best rather than following the mercantilist doctrine of national self-sufficiency.1 Following Smith's thoughts, the protection of trade as a government policy actually reduced in England.

Competition was important in the society that Smith proposed. Competition assured that each person and nation would do what they were best fitted to do, and it assured each one the full reward of their services and the maximum contribution to the common good. Therefore, the role of the government, or sovereign, should be minimum. Smith argued as follows:

All systems either of preference or of restraint, therefore, being thus completely taken away, the obvious and simple system of natural liberty establishes itself of its own accord. Every man, as longas he does not violate the laws of justice, is left perfectly free to pursue his own interest his own way, and to bring both his industry and capital into competition with those of any other man… According to the system of natural liberty, the sovereign has only three duties to attend to: three duties of great importance, indeed, but plain and intelligible to common understandings; first, the duty of protecting the society from the violence and invasion of other independent societies; secondly, the duty of protecting, as far as possible, every member of the society from the injustice or oppression of every other member of it, or the duty of establishing an exact administration of justice; and, thirdly, the duty of erecting and maintaining certain public works and certain public institutions, which it can never be for the interest of any individual, or small number of individuals, to erect and maintain; because the prof it could never repay the expence to any individual or small number of individuals, though it may frequently do much more than repay it to a great society.

(Smith, 1776, p. 445–446)

The most important economic policy of government was thus to eliminate monopolies and preserve competition. However, Smith's position on the government regulation was not absolute. As shown in the third duty of the government, Smith admitted that necessary projects that were too large for private enterprise should be undertaken by public authority. He also believed The Navigation Acts, requiring the use of English vessels to transport goods to and from England, were necessary to safeguard the marine service as a matter of national defense. Smith said, "The act of navigation is perhaps the wisest of all the commercial regulations of England." (Smith, 1776, p. 344)

It has often been said that it was more than a coincidence that both the Declaration of Independence and The Wealth of Nations were given to the world in 1776. One was a declaration of political freedom. The other was a declaration of commercial independence. The effect of The Wealth of Nations was revolutionary. Smith's thoughts on trade gave businessmen a significant place in history. Their pursuit of profit was justified. Their social respectability as an important class was identified. In the same year of 1776, individuals attained political freedom in the U.S. and economic freedom in England.

COMPARATIVE ADVANTAGE

Since Adam Smith published his book in 1776, many economists have made important contributions to this theory. Among them, David Ricardo's contribution to international trade theory was so important that this classical theory is sometimes referred to as Ricardian theory.2 There was a problem with the theory of absolute advantage. What if one country had an absolute advantage in both goods? According to Smith, such a superior country might have no benefits from international trade. In contrast, according to Ricardo, the superior country should specialize where it has the greatest absolute advantage and the inferior country should specialize where it has the least absolute disadvantage. This rule is known as the theory of comparative advantage. One important implication of this theory is that even if a country did not have an absolute advantage in any good, this country and other countries would still benefit from international trade.

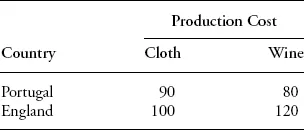

To explain this, Ricardo used an illustration as shown in Table 1-1 (see “On Foreign Trade” in Ricardo, 1817). In trade between England and Portugal, if Portugal could produce cloth with the labor of 90 men and wine with the labor of 80 men, and England could produce the same quantity of cloth with 100 men and the wine with 120, it would be advantageous for these nations to exchange English cloth for Portuguese wine. By concentrating upon what each nation could do with the least effort, each had a greater comparative advantage. Thus each nation had more wine and more cloth than it could have had by producing each commodity independently without the benefit of exchange.

In this example, Portugal can benefit from trading with the less efficient England because Portugal's cost advantage is relatively greater in wine than in cloth. Portugal's production cost of wine is only two-thirds the cost in England, but its cost of cloth is nine-tenths the cost in England. Portugal has thus greater efficiency in wine than in cloth, while England has less inefficiency in cloth than in wine.

Ricardo used another illustration which resulted in the same point. Two men could both make shoes and hats, and one was superior to the other in both employments; but in making hats, he could only exceed his competitor by one-fifth or 20 percent, and in making shoes he can exceed him by one-third or 33 percent. Would it not be for the interest of both, that the superior man should employ himself exclusively in making shoes, and the inferior man in making hats? Ricardo contended that imports could be profitable to a nation even though that nation could produce the imported article at a lower cost. Therefore, it was not true, as Adam Smith believed, that under free trade each commodity would be produced by that country which produced it at the lowest real cost.

It is the principle of comparative advantage that underlies the advantages of the division of labor, whether between individuals, regions, or nations. The Ricardian model of international trade is thus a very useful tool for explaining the reasons why trade may happen and how trade increases the welfare of the trading partners. However, this model is incomplete. In particular, there are two major problems. First, the simple Ricardian model predicts an extreme degree of specialization, but in practice, countries produce not one but many products, including import-competing products. Second, it explains trade based on differences in productivity levels between countries, but it does not explain why these differences exist.

The first problem can be solved when we assume diminishing returns to scale (i.e., a convex production possibility frontier), implying that as resources are shifted from one sector to another sector, the opportunity cost of each additional unit of another sector increases. Such increasing costs may arise because factors of production vary in quality and in suitability for producing different commodities. Under these circumstances, the theory can predict that a country will specialize up to the point where gains from specialization become equal to increasing costs of specialization. The theory can then explain the reason why a country does not specialize its production completely. The second problem is solved by the theory of factor endowments.

Table 1-1 Ricardo's Comparative Advantage

FACTOR ENDOWMENTS

Ricardo explained that comparative advantage arises from differences in labor productivity, but did not satisfactorily explain why labor productivity is different between countries. In the early twentieth century an important new theory of international trade, the Heckscher-Ohlin (HO) model, was developed by two Swedish economists.3 Heckscher and Ohlin argued that comparative advantage arises from differences in factor endowments. According to the HO model, there are two basic characteristics of countries and products. Countries differ from each other depending on the factors of production they possess. Goods differ from each other depending on the factors that are required in their production. The HO model says th...