![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Introducing Oppenheimer

OPPENHEIMER RECONSIDERED

The Honorable Jeff Bingaman

United States Senator from New Mexico

The story of Robert Oppenheimer is as timely as today's news and as timeless as a Greek tragedy. He was a brilliant scientist who devoted his talents to the service of his country. He was celebrated for making the atomic bomb and vilified for not wanting to make the hydrogen bomb. He helped unlock the secrets of the atom for his country and, in the end, his Government would not trust him with those secrets.

Senator Jeff Bingaman

His contributions to the Manhattan Project and to Los Alamos are legendary. He came up with the idea of a central weapons laboratory, and he picked the site for it, here at Los Alamos. Although there were many brilliant scientists and engineers who made enormous contributions to the Manhattan Project, Oppenheimer's contribution was unique. He was the Laboratory's first director; he recruited its original staff, and he led it to its wartime success.

Shortly after the war, Dr. Oppenheimer spoke eloquently of the Manhattan Project as having “led us up those last few steps to the mountain pass; and beyond there is a different country.” He left Los Alamos and the Manhattan Project once the height was scaled, but he continued to help us find our way through the new country. He felt a deep responsibility for his work on the Manhattan Project and thought it was his duty to continue to make his technical experience and judgment available to the Government.

For nine years after the war ended, the Government drew heavily upon his talents. He served faithfully on numerous defense and nuclear policy committees. He chaired the General Advisory Committee to the Atomic Energy Commission. Under his leadership, the General Advisory Committee promoted the development of this Laboratory, the production and perfection of atomic weapons, and the development of nuclear reactors for submarines and naval propulsion. But he (and a majority of the General Advisory Committee) opposed the development of the hydrogen bomb.

It was Dr. Oppenheimer's opposition to the H-bomb, more than anything else, that made his opponents into enemies and fueled their suspicions of his loyalty. Undoubtedly, Oppenheimer had friends and relatives who were Communists. Most of those associations had been formed long before the war and most had long since ended. All of them had been thoroughly scrutinized by the Army when it cleared him in 1943 and by the Atomic Energy Commission when it cleared him in 1947. They now became the basis of new allegations. In December 1953, the Atomic Energy Commission formally charged him with disloyalty and suspended his security clearance.

Dr. Oppenheimer replied, with great dignity, that he had no desire to retain an advisory position if his advice was not needed, but that he could not ignore the suggestion that he was “unfit for public service.” He decided to answer the charges against him and asked for a hearing to clear his name. What he got was not the objective “inquiry” called for by the Atomic Energy Commission's rules. It was a trial—there is no other word for it—and a grossly unfair one at that.

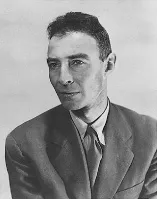

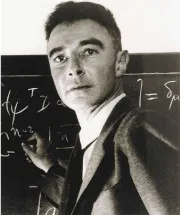

J. Robert Oppenheimer

The charges against Dr. Oppenheimer were long and complex. Most involved his past associations, which had already been had already been thoroughly and repeatedly invested. But the Commission went further and charged him with having “expressed” views opposing the development of the H-bomb. That was the crux of the matter.

Dr. Oppenheimer was tried, in secret, before a specially-appointed three-member personnel security board. He was prosecuted by an aggressive former criminal prosecutor specially retained for the case. The FBI bugged Oppenheimer's conversations with his lawyers and potential witnesses, and reported what it heard to the Commission. Evidence was withheld from Oppenheimer and his attorneys. Legal standards were lowered to meet the evidence. The whole affair was carefully orchestrated by the AEC's chairman, Lewis Strauss.

In the end, all three board members found Oppenheimer loyal, but two of the three concluded that he was a security risk and recommended that his security clearance not be restored. They found that his failure to give “enthusiastic support” to the H-bomb program and his “highly persuasive influence” among fellow scientists were not in “the strongest offensive military interests of the country.”

Dr. Oppenheimer appealed the board's decision to the five-member Atomic Energy Commission. The Commission, by a four-to-one vote, found Oppenheimer to be loyal, but by a different four-to-one vote, found him to be a security risk. The Commission steered clear of the H-bomb charges, though they probably played a role in its decision. Instead, the majority based its decision on Oppenheimer's character and his associations.

On June 29, 1954, fifty years ago on Tuesday, the Atomic Energy Commission formally revoked Dr. Oppenheimer's clearance, forever ending his involvement in the atomic energy program. Ironically, Dr. Oppenheimer's term on the General Advisory Committee had expired two years before. His only remaining contact with the AEC was a consulting contract, which was scheduled to expire, along with his security clearance, the next day anyway.

History will be a fairer judge and will reach a truer verdict than the Commission. Robert Oppenheimer will be remembered, I believe, as a brilliant scientist who applied his talents loyally and unstintingly to our national defense. He will be remembered, too, as one who thought deeply about the forces unleashed by the Manhattan Project, and realized how essential it is for mankind to use wisely, in his words, “the new powers, the new alternatives, of an advancing mastery of nature” for “his welfare and his freedom, and not his destruction.”

The clouds over Robert Oppenheimer's reputation have long since begun to dissipate. His many friends and supporters, both in the Government and in the scientific community, never doubted his loyalty. One such supporter was Senator Clinton P. Anderson. When President Eisenhower nominated Dr. Oppenheimer's nemesis, Lewis Strauss, to be the Secretary of Commerce, Senator Anderson led the opposition to the nomination. Lewis Strauss had given Senator Anderson many reasons to oppose his nomination over the years, but his abusive treatment of Dr. Oppenheimer was chief among them. The Senate rarely rejects a cabinet nomination, but at Senator Anderson's urging, the Senate rejected Lewis Strauss’ nomination in 1959.

In 1963, President Kennedy selected Dr. Oppenheimer to receive the Enrico Fermi award, which President Johnson bestowed on him after President Kennedy was assassinated. In 1994, the FBI publicly announced that allegations that Dr. Oppenheimer had shared secrets with the Soviets were “unfounded.”

I have sought to add to these efforts by sponsoring, along with Senator Domenici and Senator Feinstein, a Senate resolution recognizing Dr. Oppenheimer's loyal service and contributions to the nation. The Senate unanimously agreed to the resolution Thursday evening.

In closing, I commend the Atomic Heritage Foundation for holding this conference and for its efforts to preserve the Manhattan Project properties here at Los Alamos and at other sites. I support these efforts and have sponsored legislation in the Senate to have the Secretary of the Interior consider adding the major Manhattan Project sites to the National Park System. The Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources approved the bill in April and it is now awaiting action by the full Senate. I think it is important that we save this significant part of our history and our heritage for future generations.

ROBERT OPPENHEIMER:

KING OF THE HILL

Richard Rhodes

Author of “The Making of the Atomic Bomb” and “Dark Sun”

The Manhattan Project is fading into myth. Sad to say, the last of its first-rank leaders, Hans Bethe, today lies mortally ill. The letter from Einstein to Roosevelt eclipses the British MAUD Report. Los Alamos, a laboratory on a mesa surrounded by a wilderness, a small coterie of scientists witching historic transmutations, eclipses armies of workers and vast factories at Hanford and Oak Ridge. Hiroshima eclipses Nagasaki, poor Nagasaki, even as the war in Europe with its epic D-Day extravaganza eclipses the longer and crueler Pacific War. And to our point here today, Robert Oppenheimer, a century after his birth on April 2nd, 1904, is rapidly eclipsing General Groves and half a hundred others as the shining talent, the indispensable leader of the project, the Prospero of this historic Tempest.

Richard Rhodes

Photo by Gail Evenari

The true history, as we all know, was far otherwise: The MAUD Report and three successive National Academy of Sciences reports turned the tide; the first bombs were designed and built at Los Alamos, to be sure, but the armies of workers and the vast factories produced their rare materials. Nagasaki suffered equally with Hiroshima for the Japanese leadership's refusal to surrender. Russian determination, Allied Lend-Lease and invasion achieved victory in Europe, but it needed atomic bombs to end the Pacific War. And no one who was part of the Manhattan Project, even within the close, intense community here on the Hill, doubted that General Groves was in charge. Nor did the project lack for other colorful characters, larger than life-sized: Bethe, Edward Teller, Ernest Lawrence, Enrico Fermi, Vannevar Bush, Arthur Compton, Leo Szilard, Harold Urey, Luis Alvarez, Emilio Segre, Eugene Wigner, Crawford Greenewalt, Paul Tibbets, Ken Bainbridge, I. I. Rabi, George Kistiakowsky, Deke Parsons, and of course Klaus Fuchs and many others—people whom I and many of you here knew in person, though I was not fortunate enough to meet Oppenheimer while he was alive.

It's worth asking why one man, Robert Oppenheimer, should emerge from such a rich and crowded field of candidates as the iconic central figure of what is arguably the single most important historic development of the twentieth century. I hope today's symposium of Oppenheimer experts will at least begin to answer that question, if an answer is possible to so obscure a phenomenon as the making of myth.

That Robert Oppenheimer's complexities should be reduced to a mythical unity is ironic; his contemporaries found him various indeed. Tall, thin, handsome, brilliant, with piercing blue eyes, chain-smoking, intense, elegant, witty, cruelly dismissive when he chose to be, generous, passionate, idealistic, but also divided within himself and by his own admission self-loathing, he seemed different men to different people. Edward Teller told me that Robert Oppenheimer was the finest lab director he had ever known, and I took that assessment seriously: praise from a man's worst enemy is praise indeed. Hans Bethe told me Oppenheimer was able to direct the effort at Los Alamos so successfully because he was so much smarter than everyone else, and Bethe included himself in that comparison. Bethe told me also—a more telling insight, I think—that Oppenheimer had been casually cruel to people who made mistakes around him, including Bethe, before the war and after the war, but that he suspended the hostilities at Los Alamos.

J. Robert Oppenheimer

Chester Barnard, president of New Jersey Bell, described Oppenheimer in 1947 as “an extraordinary man who worked very hard and always seemed to be on the verge of a nervous breakdown.”4 His students and his friends saw him differently from his enemies, of course; to Lewis Strauss, Boris Pash and William Borden, among others, Oppenheimer was a Machiavellian schemer and a Communist spy. To Oppenheimer's enemies, in the terrible security hearing they imposed on him that condemned him to internal exile and destroyed him, tough-minded I. I. Rabi had the irrefutable rebuttal:

The suspension of the clearance of Dr. Oppenheimer, [Rabi told the Gray Board,] was a very unfortunate thing and should not have been done […] against a man who had accomplished what Dr. Oppenheimer has accomplished. There is a real positive record, the way I expressed it to a friend of mine. We have an A-bomb and a whole series of it, and what more do you want, mermaids?5

Rabi knew him well:

He was an aesthete, [Rabi described Oppenheimer to Bill Moyers.] I don't think he was a security risk. I do think he walked along the edge of a precipice. He didn't pay enough attention to the outward symbols. He was a very American person of a certain kind. A certain kind of intellectual, aesthetic person of the upper middle classes.6

On another occasion Rabi assessed his friend's personal conflicts and their consequences for his science:

I found him excellent, [Rabi said.] We got along very well…I enjoyed the things about him that some people disliked. It's true that you carried on a charade with him. He lived a charade, and you went along with it. It was fine—matching wits and so on. Oppenheimer was great fun, [Rabi goes on,] and I took him for what he was. I understood his problem…[His problem was] identity…He reminded me very much of a boyhood friend about whom someone said that he couldn't make up his mind whether to be president of the B'nai B'rith or the Knights of Columbus. Perhaps he really wanted to be both, simultaneously. Oppenheimer wanted every experience. In that sense, he never focused. My own feeling, [Rabi concludes,] is that if he had studied the Talmud and Hebrew, rather than Sanskrit, he would have been a much greater physicist. I never ran into anyone who was brighter than he was. But to be more original and profound I think you have to be more focused.7

I am certainly not competent to judge if Oppenheimer's science was less original and profound than it might have been. Perhaps Rabi was. Others today will discuss other periods of Oppenheimer's life and career and perhaps address Rabi's contention as well. I want to look briefly at what I believe to be Oppenheimer's greatest achievement after the bomb itself, an original and profound achievement indeed, and neglected in something of the same way that the original discovery of the antibiotic properties of penicillin was neglected, resting in the files waiting to be pulled out and understood for what it is; the only ultimate answer to the hard, cruel fact of the bomb, to Curtis LeMay's “the bombers always get through” and William Borden's “there will be no time”: I mean the Acheson–Lilienthal Report that Oppenheimer in 1946 guided his four colleagues on Acheson's panel of expert consultants to prepare.8

In the curious way of government reports—John Manley once commented sardonically that “quite contrary to the way I thought things were [in Washington,] you don't do staff work and then make a decision. You make a decision and then do the staff w...