![]()

Chapter 1

A Day without Yesterday

Man is equally incapable of seeing the nothingness from which he emerges and the infinity in which he is engulfed.

Blaise Pascal, Pensées (1670)

Not only is the universe stranger than we imagine, it is stranger than we can imagine.

Sir Arthur Eddington (1882–1944)

1.1. Instant of Creation

In an instant of creation about 14 billion years ago the universe burst forth, creating space where there was no space, and time when there was no time. It was so hot and so dense that not even nucleons, the building blocks of atomic nuclei, had as yet formed. Until about 1/100,000th of a second all that existed was an intense fire and primitive particles called quarks and electrons and all their heavier kin together with their antiparticles; in a sense, these were the elementary particles conceived of by two early Greek philosophers of the fifth century BC, Leucippus and his disciple, Democritus. They evidently believed that an end must come to the reduction of matter into smaller parts, which they called atomos. Indeed, elementary particles that we call quarks have been discovered at last in our own time and all attempts to reduce them further have failed.

After that first brief moment, the quarks coalesced into neutrons, protons and other versions of these nucleons, never to be free again. In that inferno the lightest elements—deuterium and helium—were forged from the neutrons and protons during the next few minutes. These two primordial elements make up fully one-quarter of the mass in the universe today. Almost all the remaining mass is in that simplest element—hydrogen—consisting of one proton orbited by one electron. The hydrogen nuclei that were formed in the first fraction of a second are the same that pervade the universe now.

In the very earliest moments, there must have been a slight lumpiness in an otherwise uniformly expanding universe. As the expansion progressed, gravity acted upon those lumps, attracting surrounding matter—the primordial hydrogen and helium—into great tenuous clouds of chaotically swirling gases and the radiation that was trapped inside them. As the radiation slowly leaked from their surfaces and the clouds cooled, they began to collapse and fragment to form proto-galaxies, some slowly turning in one direction, others in another, so that in sum there was no rotation.

As the proto-galaxies collapsed further, conservation of their angular momentum caused them to whirl ever faster, just as an ice skater—who goes into a whirl with arms outstretched and draws them in—whirls faster. As each cloud fragment collapsed, it was flattened like a pancake with a central bulge by the increasingly rapid rotation, like the Andromeda Galaxy shown in Figure 1.1. At last a balance was reached between the force of gravity that would cause total collapse, and the centrifugal force of rotation, that would spin matter off into space. Because of instabilities within the thin disks, the clouds fragmented further to form stars, some larger than our Sun, and many more of them smaller.

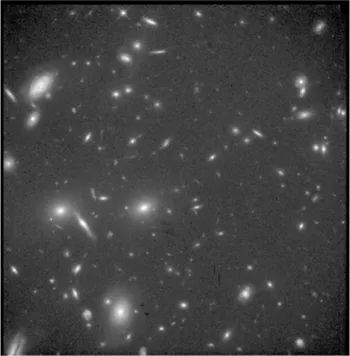

When galaxies were first observed in the first century as faint nebulous objects in the sky it was not known that they were enormous collections of stars (Figure 1.2). Al Sufi was an astronomer in the court of the Emir in Persia. He observed the great galaxy, Andromeda, as a faint nebulous patch, which he called “little cloud” in his famous Book of Fixed Stars in 964 A.D. And he described other nebulae, some of which are not galaxies at all, but rather dense clouds of gas and dust in our own galaxy, the Milky Way. The Witch Head Nebula, shown in the preface, is one of many beautiful nebula, some of which have an appearance that reminds us of an animal, or of a mythological figure.

Not until the late 1700s did William Herschel speculate that some of the hazy patches that he could see among the stars with his telescope were actually “island universes” like our own galaxy, lying far outside it and containing vast numbers of stars. For his accomplishments, William Herschel was knighted by George III of England. His sister, Caroline, too (Figure 1.3) made many important discoveries and was the first woman to be recognized as an astronomer with a salary from the King. By the end of her long life she had reaped numerous honors including the gold medal of the Royal Astronomical Society (England).

Fig. 1.1 The Andromeda Galaxy (M31), was first recorded by the Persian astronomer Al Sufi (903–986 A.D.) living in the court of Emir Adud ad-Daula. He described and depicted it in his Book of Fixed Stars (964 A.D.) and called it the “little cloud.” The galaxy is composed of about 400 billion stars. It lies relatively close to our own galaxy, the Milky Way, and is rather similar, having a central bulge and flat disk in the form of spiral arms. Relatively close in this context means 2,900,000 light-years (or equivalently a thousand billion kilometers). The two galaxies are attracting each other and will collide and pass through each other, causing distortion of each. Eventually, they will merge. Two smaller elliptical galaxies M32 and M110 (the two bright spots outside the main galaxy) are in orbit about Andromeda. The myriad foreground stars are in our own galaxy. Credit: George Healy obtained this color image of spiral galaxy M31, the Great Galaxy in Andromeda, together with its smaller elliptical satellite galaxies.

But it was not until the 1900s that astronomers using more powerful telescopes were actually able to discover that the Milky Way contains about four hundred billion stars. It is a giant among galaxies having a mass of about 600 billion to a trillion times the mass of our Sun; it is exceeded in our neighborhood only by the Andromeda Galaxy, which is generally regarded as the most distant object visible to the human eye. At a distance of 2.2 million light-years, it appears as a fuzzy patch of light in the night sky. But only the bright core of the galaxy can be seen by the eye. The full extent of the galaxy covers over 3 degrees of sky on its longest side. The Milky Way is falling towards our nearest large neighbor, the Andromeda Galaxy, M31, attracted by its great mass. In about 10 billion years the two systems will collide and merge. The end product of this merger is likely to be an elliptical or spherical galaxy with a very high concentration of stars and gas at its center, and very diffuse beyond, gradually fading into nothingness.

Fig. 1.2 Many galaxies, such as the one in Figure 1.1 are seen in this deep view of distant galaxies. Some are similar to our own, the spiral galaxies, seen at various angles. Others are spheroids or ellipsoids, called elliptical galaxies. Credit: NASA, ESA, and the Hubble Heritage Team (AURA/STScI).

Fig. 1.3 Caroline Herschel (1750–1848), winner of many awards for her work in astronomy including the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society (England), and the Gold Medal of Science by the King of Prussia, first woman to be recognized and salaried as a scientist by King George III.

Ten percent of galaxies are estimated—based on modern observations—to possess planetary systems containing large Jupiter-like planets, and no doubt many others too small to detect, perhaps some like Earth. Besides our own Sun and its planets, there are 133 other known planetary systems in our galaxy, containing at least 156 planets in orbit around main sequence stars. It is very probable that there are many smaller planets in these systems, but it is easiest to detect massive planets because their effect on the host star is more apparent. Consequently, this number increases from year to year as more sensitive detection instruments are put into play.

At the center of our galaxy, as appears to be the case with others, li...