![]()

Section 1

A Bird’s-Eye View of

Medical Education

![]()

1 Basic Educational

Competencies of

a Medical Teacher

The Latin verb docere for “teach” is also the root for the noun “doctor”. So, it would seem that teaching is part and parcel of being a doctor. In reality, of course, there are at least three roles for staff in academic medicine: clinical care, research, and teaching. All clinical staff receive training for clinical care in medical schools and beyond. Sound training in research is provided through continuing education. Good teaching also involves skills that must be learnt.

What are these skills? Is there a minimum knowledge base or set of skills that medical staff should possess before they qualify to become teachers? Few would disagree with the suggestion that medical teachers should have basic educational competencies. The more difficult task is to achieve a consensus in specifying these competencies.

We envision that medical teachers should have basic knowledge and competencies in the following domains: (1) a firm understanding of fundamental educational principles as applied to medical education; (2) an understanding of the basics of curriculum design; (3) competency in a range of instructional methodologies; and (4) the ability to choose and administer proper assessment methods.

We suggest that these basic tenets should be further deliberated, refined, and developed into institutional standards as essential requirements for medical teachers. In the following discussion, we expand the theme and very briefly highlight the key innovations and essential concepts.

Educational Principles

Educational practice should be grounded on sound educational principles. Educational practice without a sound theoretical construct is unlikely to be effective. While we acknowledge that teaching and learning theories can be dry and boring topics, nevertheless medical teachers need to be conversant with them to understand the rationale for innovations and current trends in medical education. They also need to be fluent in the common terminology pertinent to medical education.

In a general sense, medical education has been transformed by the several powerful theories of learning including learner-centered learning, experiential learning, self-directed learning, and deep learning. These enable us to get a better understanding of the learning processes of our students. We recognize the importance of learning the skills of learning (metacognition). The characterization of our students as learners is not merely a semantic distinction; it embodies learning as the key driver of the educational process.

Curriculum Planning and Design

The majority of medical teachers spend most of their teaching time directly engaged with the learners. However, some are asked to contribute to curriculum planning and evaluation, while others are deeply involved in developing modules or a specific segment of the curriculum. Thus, medical teachers should possess a fundamental understanding of curriculum planning and evaluation, including developing a module or learning plan.

One of the major criticisms of the traditional curriculum is the excessive amount of information that medical students are asked to “learn” due to the explosion of knowledge in biomedical sciences. The burden is compounded by unplanned repetitions of content over the years. Besides, a great deal of learned content remains unutilized, as the students fail to determine the connection between the content and their practical applicability in dealing with patients.

Newer models of the curriculum promote integration and contextualization. This may take shape in various forms: between basic science subjects; between clinical sciences subjects; between basic and clinical subjects; and, increasingly, between biomedical and clinical sciences and other strands of the curriculum such as ethics, law, and medical sociology (Harden 2000).

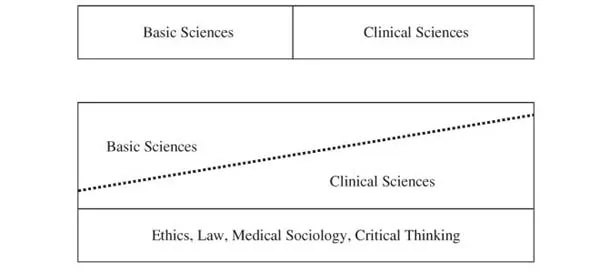

An immediate effect of such integration is the abandonment of a distinct separation between basic and clinical science years (Fig. 1). Besides, courses could be designed around body systems and functions for a more rational organization of the curriculum. Thus, medical teachers’ responsibilities include not just imparting facts, but also integrating them and making them relevant to the practice of medicine.

Fig. 1.Top: clear separation between basic sciences and clinical sciences in the traditional model of the curriculum. Bottom: basic sciences and clinical sciences are integrated, with early introduction of clinical sciences.

Instructional Methodologies

A medical teacher’s competency in the area of instructional methodology should include effective communication of the course objectives to students, knowledge and skills about several instructional methods, and the ability to choose the correct method to help students achieve the course objectives. Evidence for the effectiveness of a specific instructional method comes from myriad sources, and includes empirical research as well as personal and self-reflective research (STLHE 2002).

Thus, it is the professional responsibility of medical teachers to maintain their pedagogical competency by taking active steps to stay current with regards to teaching strategies. Just as they engage in continuing medical education to remain competent professionally, they should engage regularly in reading medical education literature, attend workshops and conferences, experiment with a range of teaching methods, and generally be able to vary their instructional strategies to meet the demands of a specific teaching situation or a particular group of learners.

The response of medical education to the above has resulted in several beneficial changes. Firstly, there are innovations and changes in practice within the traditional and well-established instructional methods such as lectures and other forms of expository learning. The major shift is to make them more active and learner-centered. Secondly, there are newer and more useful teaching and learning methods. Medical teachers do not need to be restricted to a limited number of teaching and learning methods. Small-group discussion, brainstorming, role-play, and many others are now regarded as valid and essential instructional methods. They bring variety and can be customized to suit particular teaching needs.

Thirdly, problem-based learning (PBL) and its variants have emerged as an effective way of delivering learner-centered learning. PBL emphasizes small-group and self-directed learning among the students. The content is also more integrated and, in many medical schools, training is multi-professional. Thus, medical teachers’ competency in this regard should include an understanding of the core principles and rationale of PBL, effective group facilitation skills, student assessment in PBL, and recognition of various options in PBL implementation.

The fourth major area of innovation is in clinical teaching. Unlike other forms of teaching and learning activities in medicine that share a great deal of similarity with those of general education, clinical teaching is unique to medical education. It incorporates several unique attributes such as clinical reasoning, patient-based teaching, and a tripartite interaction between students, teachers, and patients.

At the beginning of the early 1970s, the predominant hypothesis in understanding of the clinical reasoning process was that such reasoning is the result of having generic clinical problem-solving skills. This hypothesis was challenged and it is believed that a generic clinical reasoning process is nonexistent (Norman 2002). We know that clinical reasoning is greatly influenced by contextual knowledge from formal education and clinical experience.

Other areas of improvement in clinical teaching are time-efficient delivery of clinical teaching, more effective and on-the-spot needs assessment, and teaching of communication and procedural skills to the students. Several innovative models, such as “microskills”, have gained popularity, particularly among office-based clinical teachers, as an effective way of conducting clinical teaching.

Student Assessment

Assessment is an immensely important activity that all medical teachers are intimately involved with. The stakes are high–it is directly related to quality assurance and accreditation of the program. Therefore, it is the duty of the teachers to ensure that student assessment is valid, fair, and linked to the course objectives. Medical teachers’ competency in student assessment should include understanding the basic principles of assessment, recognizing the advantages and disadvantages of various assessment methods, and possessing the ability to choose and implement an assessment instrument that assesses what it intends to assess.

Major innovations that have reshaped student assessment are (1) more rigorous linking between assessment and program objectives; (2) improvements in the validity and reliability of assessment instruments; (3) emphasis on self-assessment and formative assessment; (4) assessment of attitudes and skills along with knowledge; and (5) attempts to sample actual application of the skills and behavior in practice.

There is also a greater appreciation of the limitations of student assessment. Tests are snapshots of students’ performance in a given time; they may or may not detect the broader aspects of students’ competency. To put it more figuratively, tests are like punch biopsies of a tumor–we are lucky if we get to make a clear diagnosis with only one biopsy. The chances of success improve with multiple biopsies and incorporation of varied techniques–a realization that has led to the abandonment of one-time testing with limited assessment instruments. A better approach is to develop a comprehensive and progressive assessment plan that incorporates multiple assessment instruments, each with specific strengths.

Context-rich multiple choice question, modified and short essay question, objective structured clinical assessment, and work-based assessments are some of the innovations that have gained acceptance. The student portfolio is being pioneered as an excellent developmental tool and an authentic way of documenting attitudes and personal attributes that are translated into practice. When these are combined judiciously, they are much more likely to provide a comprehensive and more accurate diagnosis of students’ competence.

Conclusion

The introduction of new curricular structures and new methods of teaching, communication of information, and student assessment has not been without resistance. Many critics feel that the old methods have worked for so many years, so why should there be any change? Others feel that student-centered methods of teaching, where the responsibility to learn is on the students, are not viable because the students are not well prepared. These critics forget that when a teacher teaches, there is no guarantee that the students learn. Thus, the goal of all medical teachers should not be merely excellence in teaching, but rather excellence in ensuring that their students are good at learning.

In summary, we have learned the following:

• Possession of content expertise alone is not enough to become an effective teacher.

• The basic minimum competencies of medical teachers include

• application of learning concepts and philosophies into practice;

• understanding of the basics of curriculum planning and implementation;

• ability to plan and execute an educational program;

• awareness of the range of instructional methodologies; and

• ability to choose and administer proper assessment methods.

• The major innovations in medical education include

• integrated and flexible curriculum models;

• problem-based and case-based learning, greater use of small groups, role-play, and other forms of collaborative and group learning;

• understanding of the nature of medical expertise and clinical reasoning; and

• development of assessment methods that are more valid and reliable for the intended purpose.

References and Further Readings

- Bland CJ, Schmitz DC, Stritter FT, Henry RC, Aluise JJ. Successful Faculty in Academic Medicine: Essential Skills and How to Acquire Them. Springer Publication Company, New York, USA, 1990.

- Friedman-Ben David M, Davis MH, Harden RM, Howie PW, Ker J, Pipperd MJ. Portfolio as a Method of Student Assessment. AMEE Education Guide 24. Association of Medical Education in Europe, Dundee, UK, 2001.

- Harden RM. The Integration Ladder: A Tool for Curriculum Planning and Evaluation. Medical Education34:551-7, 2000.

- Harden RM, Crosby J. The Good Teacher Is More Than a Lecturer–The Twelve Roles of the Teacher. Medical Teacher22(4): 334-7, 2000.

- Mathers NJ, Challis MC, Howe AC, Field NJ. Portfolios in Continuing Medical Education–Effective and Efficient? Medical Education33:521-30, 1999.

- Norman G. Research in Medical Education: Three Decades of Progress. British Medical Journal324:1560-2, 2002.

- Society for Teaching and Learning in Higher Education (STLHE). Ethical Principles in University Teaching. Canada, 2002. Web address:http://www.umanitoba.ca/uts/documents/ethical.pdf/. Last accessed July 2007.

- Tavanaiepour D, Schwartz PL, Loten EG. Faculty Opinions about a Revised Pre-clinical Curriculum. Medical Education36:299-302, 2002.

![]()

2 Historical Perspectives

in Medical Education

Scientists, by reputation, are supposed to be open to ideas, as long as those ideas can be–and are–tested. Let us find faculty who are open to ideas about the management of medical education; let us then test ideas in an atmosphere of mutual trust in our effort to provide the best educational program for the preparation of physicians–which is after all the one mission uniqueto a medical school.

–Stephen Abrahamson (1996)

The practice of medicine is perhaps as ancient as the human race itself. A brief account of the history of medical education gives us an interesting reference point to analyze the contemporary debates in medical education, understand the context and complexity of practice, and recognize the similarities and differences between past and current practices and potential future trends.

At the very beginning, the teaching of medicine appeared to be based on a teacher-pupil apprentice model. There were not many organized teaching hospitals. The gurukul system was the mainstay of the teaching of medicine in ancient India; under this system, an astute medical practitioner would guide and personally supervise the growth of a limited number of trainees. The first modern teaching hospital was set up in Baghdad, Iraq, around the 10th century. It was a multi-professional hospital with physicians, surgeons, oculists, pharmacists, administrators, kitchen, hospital managers, and library. This was a place for teaching students both practice and theory, and was open to all levels of society including chronically ill patients. Around the same time, the Arabic physician-educator, Al-Razi, defined a code of ethics for doctors that is still remarkably relevant today. The code of ethics includes being honest, skilled in the art, resourceful, kind, and compassionate; aiming treatment at patient improvement; keeping confidentiality; refraining from evil and vice; and visiting patients in the hospital regularly.

Prior to the 18th century, in Europe and America, the learned study of medicine in the preparation for practice as a physician was limited to members of the social classes who had access to university study. Their patients also tended to be from the same landed and affluent classes. Medicine was studied in university based on the classics of medicine and literature. Latin was predominantly the language of instruction. It was not the same as the practical hands-on work of the surgeons, pharmacists, and other healers.

The situation changed towards the end of the 18th century as advances in science led to the introduction of new subjects such as chemistry, botany, and physiology in the university. Even in the traditional medical subjects such as anatomy, mat...