![]()

Part 1

Development Stages

This Part reviews Malaysia’s economic growth and structural change over the last five decades since Malaya (later Peninsular Malaysia) gained independence in 1957 and Malaysia was formed six years later in 1963 with the inclusion of the Borneo states of Sabah and Sarawak. Specific emphasis is given to the economic role of government, particularly in terms of public finance and spending by the federal or central government. This should make clear that Malaysia’s generally impressive post-colonial economic development has been largely due to appropriate government interventions and reforms, rather than simple reliance on market forces, as often suggested in much of the literature on the country. At least five regimes with different priorities can be distinguished in Malaysian economic development from 1957 to the end of the Mahathir era in late 2003.

Before the Japanese Occupation during the Second World War, there was no pretence of colonial government planning. In fact, before the colonial creation of the Malayan Union in 1946, there was no unified government of the peninsula. The Straits Settlements of Penang, Melaka and Singapore were outright colonies while British influence was more pronounced despite indirect rule in the Federated Malay States of Perak, Selangor, Negri Sembilan and Pahang as well as Johor compared to the other northern Unfederated Malay States of Kedah, Perlis, Kelantan and Terengganu. This changed during the Emergency authority over plan formulation and implementation rested with senior British officials mainly concerned with imperial interests and committed to protecting the predominantly British plantation and mining interests in Malaya.

The colonial bias for these interests was reflected in public development expenditure that prioritized economic infrastructure to service the primary commodity export economy. As Britain’s most profitable colony, Malaya provided much of the export earnings that financed British post war reconstruction. Legal developments during this era played an important role in shaping and developing British Malaya. During the early and mid-1950s, the colonial government initiated reforms, including rural development and affirmative action efforts. (For an alternative view suggesting that colonial and post-colonial governments were mainly concerned with ensuring social and political stability, rather than advancing British corporate interests, see Drabble, 2000).

Independence in 1957 was followed by a dozen years of post-colonial economic diversification with limited government intervention. Generally laissez faire policies were pursued, with some import-substituting industrialization, agricultural diversification, rural development and ethnic affirmative action efforts. A period of growing state intervention followed the post-election race riots of May 1969. The New Economic Policy (NEP) legitimized increasing government intervention and public sector expansion for inter-ethnic redistribution and rural development to reduce poverty. Export-oriented (EO) industrialization also generated considerable employment, especially for women, while increased petroleum revenues financed rapidly growing state spending.

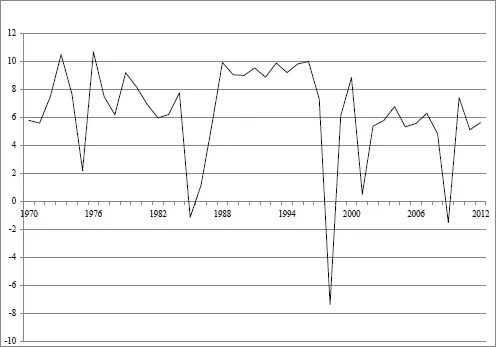

Malaysian economic performance has been very susceptible to changes in global economic conditions as indicated in Figure 1.1. But Malaysian economic vulnerability has changed over time. Earlier, vulnerability to commodity prices was very important, but later, changing demand for manufactured outputs has become more significant. Especially since the 1990s, the Malaysian economy has become more vulnerable to movements on the capital account, as during the 1997–1998 and 2008–2009 crises, when easily reversible portfolio capital inflows were quickly reversed with destabilizing consequences, not only for the stock market, but also for the real economy (Figure 1.1).

Expansionary public expenditure from the 1970s continued after Mahathir became Prime Minister in mid-1981. Spending was cut from mid-1982, but government-sponsored heavy industries grew as other foreign investments declined. Thus, the Mahathir regime had a different rationale for state intervention, shifting from interethnic redistribution to heavy industrialization. From the mid-1980s, the economic slowdown and massive foreign debt build-up from the early 1980s led to massive ringgit depreciation and economic liberalization. Liberalization was accompanied by privatization and greater government support for the private sector, including new investment incentives and regressive tax reforms. The new measures favouring private investment resulted in a decade of rapid growth until the 1997–1998 financial crisis led to renewed state intervention for crisis management and economic recovery, including currency controls and bail out facilities for the banking sector and favoured corporate interests.

Figure 1.1 Malaysia: Economic Growth, 1970–2012 (% per annum)

Sources: Calculated with data from Bank Negara Malaysia, Monthly Bulletin of Statistics, various issues.

In the following sections, we review the major periods of Malaysian economic development policymaking since independence in 1957 and also consider economic performance indicators over the last half century. Needless to say, economic performance does not simply follow from economic policies and is influenced by other factors as well, including economic conditions, both nationally as well as internationally. We conclude with lessons from the Malaysian experience with economic development policies.

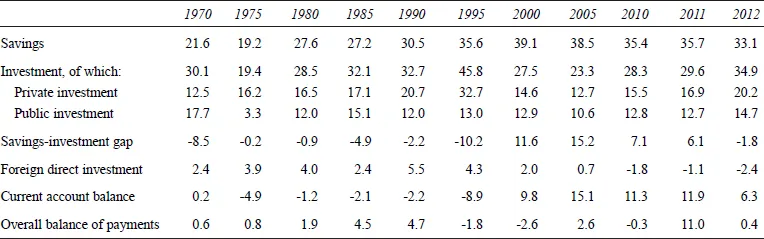

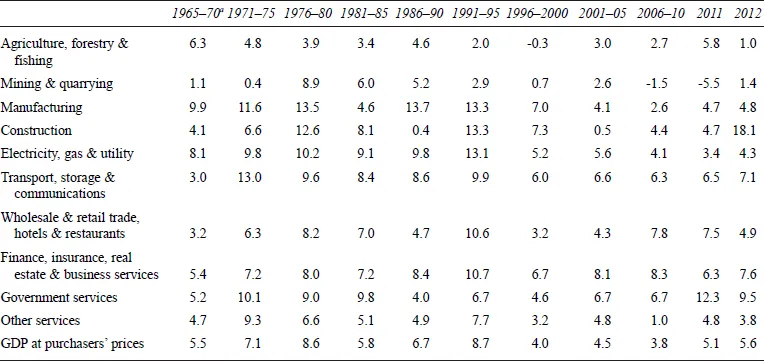

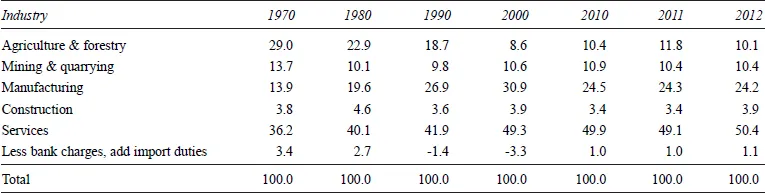

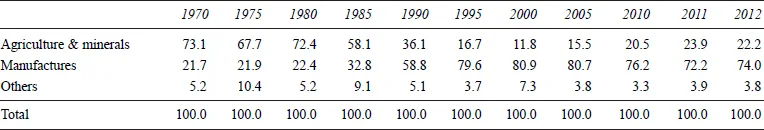

The eleven tables try to cover the entire period under consideration, but although Malaysia was formed in 1963 and took its current territorial boundaries in August 1965, data collection has lagged behind and generally begins from around 1970. The first two tables provide growth, inflation and other economic indicators. Table 1.3 tracks savings, investment and foreign direct investment trends which have, in turn, shaped sectoral growth trends in the following two tables. Tables 1.6 and 1.7 summarize the composition of exports and imports over this period, reflecting the changing openness of the Malaysian economy over time. The next three tables looks at sectoral employment growth while the last two tables reflect wage and household income trends.

The Alliance Era (1957–1969)

In preparing for political independence, the British had ensured that the leftist anti-colonial forces who threatened their economic interests were curbed, while ethnic elites committed to protecting their interests were cultivated to eventually inherit state office in 1957. With the attainment of independence in August 1957, the Alliance, a coalition of the political elites from the three major ethnic groups, formally took over political authority in Malaya. Not unlike other newly independent countries, the post-colonial government embarked upon a programme of economic development emphasizing economic diversification and industrialization. Otherwise, the basically laissez faire development path for newly independent Malaya was thus assured. The post-colonial government continued to promote private enterprise and encourage foreign investments inflows, while the economic interests of the ex-colonial power were protected.

The Alliance government’s economic development strategy reflected the class interests represented by the major parties in the ruling coalition and the political compromise among their leaders and with the Colonial power. Consistent with this compromise, the state pursued basically laissez faire policies with minimal state interference and small budget deficits except in ensuring attractive conditions for new investments. The postcolonial government was committed to defending British business interests in Malaya, which also enabled the predominantly Chinese local businesses to consolidate and strengthen their position.

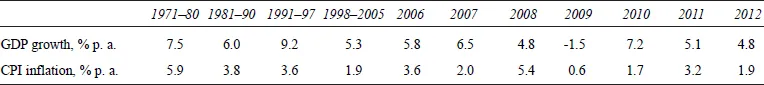

Table 1.1 Malaysia: Growth and Inflation Indicators, 1971–2012

Sources: Ministry of Finance, Malaysia, Economic Report, various issues.

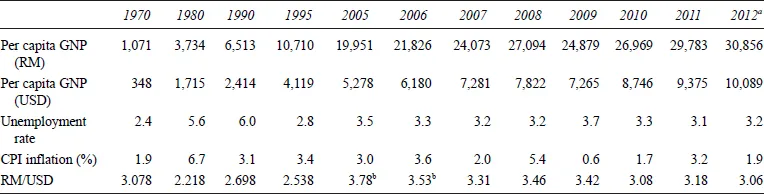

Table 1.2 Malaysia: Economic Indicators, 1970–2012

Notes: a Estimates.

b The ringgit was pegged at US$1 = RM3.80 from September 1998 – May 2006.

Sources: Ministry of Finance, Malaysia, Economic Report, various issues.

Table 1.3 Malaysia: Savings, Investment and Foreign Direct Investment, 1970–2012 (% of GNP)

Sources: Calculated with data from various Malaysia plan documents; Bank Negara Malaysia, Monthly Statistical Bulletin, May 2012; Ministry of Finance, Malaysia, Economic Report 2012/2013.

Table 1.4 Malaysia: Growth by Sector, 1965–2012 (% per annum)

Notes: GDP in 1965 prices for 1965–70; GDP in 1970 prices for 1971–80, in 1987 prices for 1981–95 and current prices for 1996–2000.

a GDP at factor cost for Peninsular Malaysia only.

Sources: 2MP, Table 2-5; 4MP, Table 2-1; 5MP, Table 2-1; 6MP, Table 1-2; 7MP, Table 2-5; 9MP, Table 2-2; Bank Negara Malaysia, Monthly Statistical Bulletin, various issues.

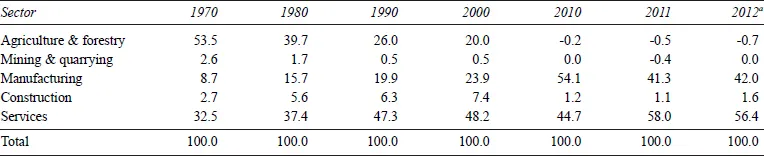

Table 1.5 Malaysia: Gross Domestic Product by Sector, 1970–2012 (%)

Note: GDP for 1970–1990 in 1978 prices, for 2000–2011 in 2000 prices.

Sources: 5MP, Table 3-5; OPP2, Tables 2-3 and 3-2; OPP3, Table 2-5; 8MP Table 2-6 and 4-2; Bank Negara Malaysia, Monthly Statistical Bulletin, December 2011, Ministry of Finance, Malaysia, Economic Report, 2011/2012.

Table 1.6 Malaysia: Structure of Exports, 1970–2012 (%)

Sources: 4MP, Table 2-5; Rasiah, Osman and Alavi (2000); Bank Negara Malaysia, Annual Report, various issues.

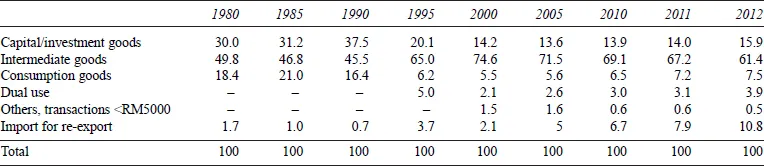

Table 1.7 Malaysia: Structure of Imports, 1980–2012 (%)

Sources: 5MP, Table 2-5; 6MP, Table 1-3; 7MP, Table 2-3; 8MP, Table 4-2; 9MP, Table 2-10; Bank Negara Malaysia, Monthly Statistical Bulletin, various issues.

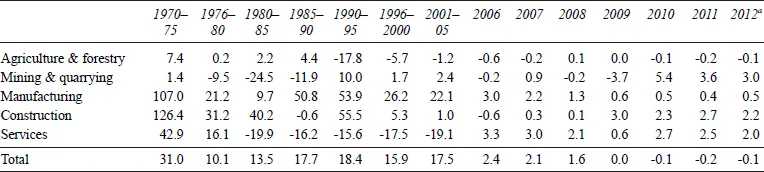

Table 1.8 Malaysia: Employment Creation, 1970–2012 (% increase)

Note: a Estimates.

Sources: Calculated with data from 5MP, Table 3-5; 6MP, Table 1-11; 7MP, Table 4-2; 8MP, Table 2-4; 9MP, Table 11-2; Ministry of Finance, Malaysia, Economic Report, various issues.

Table 1.9 Malaysia: Employment Increase by Sector, 1970–2012 (%)

Note: a Estimates.

Sources: 5MP, 3-5; OPP2, Tables 2-3 and 3-2; OPP3, 2-5; 8MP Tables 2-6 and 4-2; Bank Negara Malaysia, Monthly Statistical Bulletin, December 2011; Ministry of Finance, Malaysia, Economic Report, various issues.

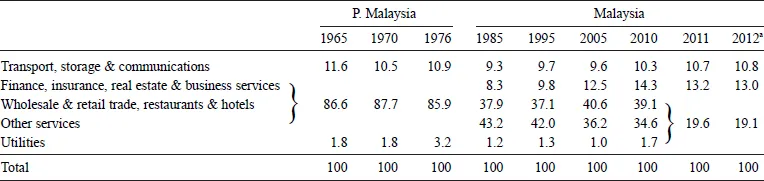

Table 1.10 Malaysia: Distribution of Services Employment, 1965–2012 (%)

Note: a Estimates.

Sources: Labour Force Survey, various issues; Ministry of Finance, Malaysia, Economic Report, various issues.

Table 1.11 Malaysia: Change in Real Wages, 1971–2012 (average % per annum)

| Period | Growth rate |

| 1971–79 | 1.58 |

| 1979–85 | 5.94 |

| 1985–90 | 1.17 |

| 1995 | 20.9 |

| 1996 | 4.4 |

| 1997 | 5.9 |

| 1998 | -2.7 |

| 1999 | -1.7 |

| 2000 | 12.9 |

| 2001 | 3.4 |

| |

| 2002 | 11.0 |

| 2003 | 4.0 |

| 2004 | 4.1 |

| 2005 | -9.1 |

| 2006 | -11.1 |

| |

| 2007 | 3.0 |

| 2008 | -6.9 |

| 2009 | 13.3 |

| 2010 | 5.2 |

| 2011 | -1.4 |

| 2012a | 5.5 |

Note: a Estimates.

Sources: Rasiah (2002), Table 14; Appendix Table 4; Ministry of Finance, Malaysia, Economic Report, various issues.

Table 1.12 Malaysia: Gross Monthly Household Incomes, 1970–2009 (RM)

| Year | Income |

| 1970a | 264 |

| 1974a | 362 |

| 1976 | 505 |

| 1979 | 678 |

| 1984 | 1,098 |

| 1987 | 1,083 |

| 1989b | 1,169 |

| 1992 | 1,563 |

| 1995 | 2,020 |

| 1997 | 2,606 |

| 1999 | 2,472 |

| 2002 | 3,011 |

| 2004 | 3,249 |

| 2007 | 3,686 |

| 2009 | 4,025 |

Notes: a Peninsular Malaysia only.

b Data from 1989 is for Malaysian citizens only.

Source: Economic Planning Unit (http://www.epu.gov.my/c/document_library/get_file?uuid=e2b128f0-c6fb-4980-8a17-3f708fc3d7a8&groupld=34492)

Development policy during this phase was therefore influenced by these compromises. The essentially laissez faire approach precluded direct government participation in profitable activities, such as commerce and industry, which were left exclusively to private business interests. Hence, a relatively low proportion of public development expenditure was allocated to commerce and industry. Within this overall strategy, the government made some highly publicized, but nonetheless feeble attempts to promote the interests of the nascent Malay business community, while also undertaking rural development programmes to secure predominantly Malay rural electoral support.

The increased allocations for social services (see Parts 2 and 3), particularly education, partly reflected the increased commitment to utilize educational expenditure to create a Malay middle class besides meeting the human resource requirements of the rapidly growing and modernizing Malaysian economy. The government increasingly regarded educational expenditure as an investment that would yield returns in the form of increased output from a more productive labour force, rather than merely as public consumption. Government agricultural development policies were essentially conservative. Rural development efforts were constrained by the government’s reluctance to act against politically influential landed, commercial and financial interests. The main thrust of rural development efforts involved new land development by the Federal Land Development Authority (FELDA), other measures to increase agricultural productivity and rural incomes, as well as greater provision of rural facilities such as roads, schools, clinics, irrigation, etc.

During the early years after independence, the major physical development initiatives in the country were reflected in the annual budgets and the five-year Malaysia Plans. Almost all the infrastructure developments undertaken before the late 1980s were financed by the government, averaging about a third of overall public expenditure. Private sector involvement in infrastructure was largely as a service provider (e.g. construction activities) and did not involve much financing or revenue collection from such developments.

Policy in the 1960s generally emphasized growth, assuming that its benefits would trickle down. Malaysia achieved impressive growth, with considerable infrastructure development, although economic diversification in both agriculture and industry was limited. The government pursued economic diversification efforts to reduce Malaya’s over-reliance on tin and rubber on two main fronts. Firstly, plantations were encouraged to grow other crops, particularly oil palm, and an increasing number of FELDA-sponsored land development schemes were also planted with oil palm. Secondly, the state encouraged manufacturing by offering incentives, and providing infrastructure and other supportive economic measures, accelerating the growth of industry.

Over the 1960s, policy was increasingly made by Alliance ministers, senior Malayan civil servants and American advisers in the increasingly complex planning process, involving more bureaucratic organs. Policy in the 1960s also saw two other major changes from the 1950s. Firstly, the state was increasingly willing to incur budget deficits, especially for development expenditure. This involved increased borrowing from both domestic and foreign sources to finance rising public sector development expenditure. Secondly, more sophisticated planning techniques were adopted, e.g. the Harrod-Domar growth model was used to estimate the investment rate required to attain certain income and employment growth targets.

The government promoted moderate import-substituting industrialization, passing the Pioneer In...