![]()

PART 4

The Committed Man

Sociology is the science which has the most methods and the least results.

— H. Poincaré —

![]()

Chapter 10

The Dreyfus Affair

The Dreyfus Affair, which unfolded from 1894 to 1906, has become the paradigmatic example of the commitment of intellectuals and scientists in a judicial, political, social and ideological debate. It has been recounted and studied so many times that we shall only do a quick review of the major episodes by illustrating them with examples taken from the multitude of newspaper articles (sometimes nauseating) that accompanied it. We will obviously focus on the role of scientists in the second and third part of the affair, that is to say from the famous “J’accuse” by Zola in 1898 and the trial that followed. And we will insist more specifically on the role of Poincaré in this scientific expertise, and how it was conveyed in the press. We deny here trying to plagiarize any serious studies that were produced on the issue before. So we take it upon ourselves to borrow from Laurent Rollet’s studies, and we officially and sincerely thank him here for his authorization and support of our undertaking.

We prefer then to name these borrowing right from this introduction. Most of them come from his very valuable contribution to the website; http://images.math.cnrs.fr/; entitled “Des mathématiciens dans l’affaire Dreyfus? Autoforgerie, bertillonnage et calcul des probabilités”: to avoid too many cross-references to footnotes, we will simply emphasize what we borrowed from this text with a *. But the borrowing also come from his chapter “L’université et la science” (University and science) from the book “Les évènements fondateurs. L’affaire Dreyfus” (The founding events. The Dreyfus Affair) directed by Vincent Duclert and Perrine Simon-Nahum and published in 2009 by Armand Colin.

10.1 The First Dreyfus Affair: A Brief Overview

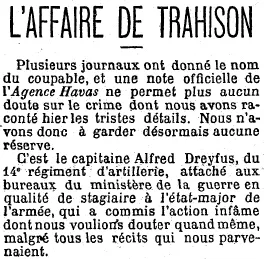

This affair essentially unfolded in three stages, although it has been the subject of a significant number of articles and debates in the intervals between these episodes. It started in November 1894 and, among the countless newspaper articles that got hold of it, we chose to refer to the French newspaper Le Figaro in an article dated of November 3. Why this choice? The first reason is that it is not the purpose of this book to recount in detail the beginning of this affair, for Poincaré doesn’t appear in it until later; besides, we would not have enough space here to put most of the substantial and almost always partisan articles which sustained the debate from the very beginning of the affair. The second reason is that this article has two very instructive points. Firstly, he shows us that right from the beginning, the press condemned Dreyfus without further ado (and way before his trial). Secondly, because this article is very well documented on the functioning of the institutions – of the army in particular, and he tells us already a priori what sanction the alleged culprit might be subjected to (for that is precisely what is at stake at the very beginning of the affair). The case had just been divulged to the press and the Figaro started its long article as follows (see Fig. 10.1):

Fig. 10.1 Le Figaro of November 3, 1894.

THE CASE OF TREASON

We can see that Dreyfus was portrayed as guilty right from the start. Let’s not forget that he was accused of high treason:

Le Figaro criticized the Ministry of War and the police headquarters which, in his opinion, were too slow to disclose the information, considering that, in the end, the case did not “affect the consideration of our army in any way.” But the article was about the “odious crime” committed by Captain Dreyfus, who was “waiting in the Cherche-Midi prison for the members of the court-martial to decide whether or not he committed the abominable crime of high treason”. However, for Le Figaro, there was absolutely no doubt that he committed it (as it was the case for most of the other newspapers at the time):

This was followed by the long list of the respective fortunes of the Dreyfus family and of his wife, “the daughter of a very wealthy diamond merchant,” who lived “in a luxurious apartment in the Avenue du Trocadéro.” And the fact that Dreyfus was a Jew quickly appeared in an almost caricatural portrait: “Captain Dreyfus, who is thirty-five years old, is of size above the average, has a quite lively complexion, is short-sighted and of a fairly pronounced Jewish type.” Therefore, right from the beginning, Dreyfus being Jewish was associated with him being necessarily guilty. Let’s not forget the social and political context of that time: Antisemitism was omnipresent in all the press, and even elected officials or intellectuals claimed to follow it; it was well-established in journals (La Libre Parole by Édouard Drumont for instance) and best-selling books (La France juive, by the same Drumont, published in 1888) which were written to spread it. Drumont, boosted by the impressive success of his book and journal, campaigned against the Jewish officers of the French army and amplified the hatred of Jews in France and in the French army. For the authorities, led by the Minister of War, General Auguste Mercier, it was of utmost importance to find a culprit – who had to be found among the officers who spent some time at the headquarters, giving them access to the documents intended for the German in the famous bordereau, in fact only document in a file where there was nothing but a presumption of treason, since this document only announced an upcoming delivery of confidential papers. Dreyfus soon turned out to be the ideal culprit: he was the only Jew who have had access to these documents, and he was then only an intern. More importantly, he came from a Republican family and began a career in an army still bruised from the fall of 1870, preparing its revenge on Germany, and whose officers were still essentially ultra-Catholics anti-republicans. In addition, the case was revealed to the general public by Drumont in La libre parole of October 24, 1894 and was thus directly placed under the perspective of the Jewish responsibility for the misfortunes of the French society: that article marked the beginning of the “Dreyfus Affair” in the public sphere. At the time, most of the press was conservative and antisemitic. Le Figaro was one of the more moderate and less biased newspapers on the subject: this is why we chose this newspaper article dated November 3, 1894 to illustrate the first part of the Dreyfus Affair “moderately”. Periodicals such as L’Eclair, La Croix, L’Intransigeant, etc.1 were much more radical. We can see then that the newspapers designated the culprit from the very start and even wrote in advance about the rest of the trial and the coming conviction of Dreyfus, as well as the penalty that he would be subjected to after a rigged and rapid trial. In the same article, Le Figaro thus explained the legislation that governed such cases. Taking the example of the Adjutant Chatelain, who in 1883 was sentenced to life imprisonment in a “fortified compound”, and who, in 1894, was still in prison in Noumea “where it is very expensive for the State to keep him, being currently the only transported convict that exists in our fortified compounds, and watching him requires a large personnel”, the newspaper announced what awaited Dreyfus. The die was then cast and Dreyfus was to be subjected to the penalty announced, as mentioned above: he did not join Chatelain in Noumea, but was deported to Guyana, on an island with a ominous name: Devil’s Island.

10.2 Three Other Trials

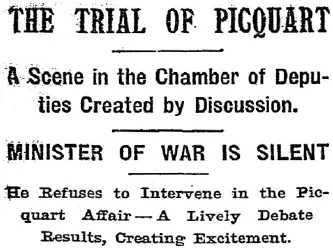

In a predominantly anti-Dreyfusard France, it was difficult to question the judgment pronounced against the captain, and the establishment of a Dreyfusard trend, then a counter-attack by the people who embodied it, was spread over two years and a half, from 1895 to 1897. Among many other protagonists, two of them, one guilty and the other innocent, took part in the case, and were the subject of two other trials which proved the first one innocent and convicted the second one, in order to cover up for the people responsible for the 1894 trial and satisfy the still highly virulent anti-Dreyfusism. These two figures were Commandant Charles Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy (1847-1923) and Lieutenant-Colonel Georges Picquart (1854-1914). The latter, appointed head of the French intelligence service in July 1895, discovered in documents stolen from the German Embassy some elements showing that Esterhazy was giving information to the Germans. Picquart also discovered a similarity between Esterhazy’s handwriting and the handwriting on the bordereau which was used to make Dreyfus found guilty of treason. Without consulting his superiors, Picquart held an investigation which led him to be absolutely certain, with supporting evidence, of Esterhazy’s betrayal and guilt in the case for which Dreyfus was convicted. When Picquart reported his findings to the General Staff, they reacted the opposite of what he expected: he became the target of an investigation conducted to prove that, on the contrary, he was the guilty one, and he was taken away and finally posted to Tunisia.

The New York Times reported on November 29th, 1898 this trial: