![]()

1

INTRODUCTION

1.1. The Development of Private Economy

in China’s Post-Reform

The Third Plenum of the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) 11th Central Committee in December 1978 initiated the market-oriented reforms and the adoption of open-door policy in China. The introduction of the household responsibility system improved farmers’ income and created a labor surplus. A set of State Council regulations on the urban, non-agricultural individual economy was issued in July 1981, which defined a new business category — single industrial and commercial proprietor. As a result, the private economic sector started to develop again. In 1983, a series of central and local regulations for the licensing and control of individual businesses, taxation, product quality and hygiene, and free markets were introduced in China. The development of private business was affected by the following “market rectification” drives. In June 1988, the State Council issued the Tentative Stipulations on Private Enterprises, where private enterprises were defined as for-profit organizations that are owned by individuals and employ more than eight people (Garnaut et al., 2012). The ownership of private enterprises range from sole proprietorship, partnerships, limited liability companies to shareholding cooperatives. Different requirements were set for registered capital and numbers of shareholders with different forms of private ownership (ADB, 2003).

Deng Xiaoping’s southern tour in September 1992 accelerated China’s transition to the rapid development of a socialist market-oriented economy. The 14th Party Congress witnessed ideological breakthrough and the establishment of a major socialist market economy was listed on the reform agenda of the national economy. The state-owned enterprises (SOEs) started to transform the ownership and undertake the reform of clarification of property rights. The Third Plenary Session of the 14th Party Congress in November 1993 decided to divest small SOEs from state control. The policy of “keeping the large and letting the small go” was carried out in 1995. The ownership structure of SOEs was diversified through a range of processes including contracting, leasing, establishing an employee-held company or cooperative, even outright privatization. In March 1999, the National People’s Congress passed an amendment to the constitution to recognize the status of the private sector. The legitimacy of private property rights was gradually accepted ideologically, politically and constitutionally (Garnaut et al., 2012).

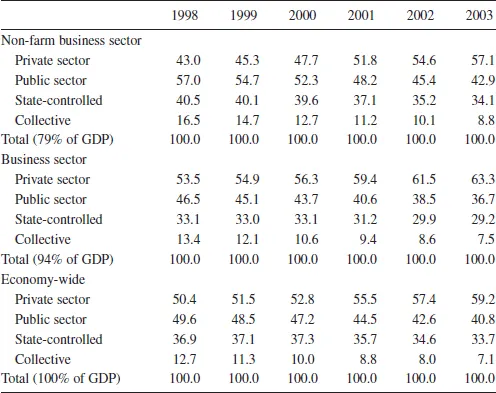

The definition of the private sector has been still vague and fuzzy in terms of enterprise types in China. The term “non-state” has been more widely used as a broader category than “private” (ADB, 2003). Nonetheless, the presence of the private sector has become increasingly significant in the Chinese economy (see Table 1.1). For the commercial business sector, the percentage of value added by private firms was estimated at 63% in 2003, up from about 54% in 1998. The private share of the non-farm business sector moved ahead of the public share for the first time between 1998 and 2003, with its share of output rising from 43% in 1998 to 57% in 2003. About one-third of the increase in the size of the private sector was reflected in a decline in the number and output of collectives, with the remaining two-thirds reflected in closure and divestment of solely state-owned firms. The state-owned share of value added fell from 58% in 1998 to 43% in 2003 with about half of this being the result of an injection of minority stakes from the private sector. In the economy as a whole, the private share of GDP rose from 50% of value added in 1998 to 59% in 2003 (OECD, 2005).

In 2005, the Chinese government opened more sectors to private investors to include infrastructure construction, financial services and even the defense industry, previously monopolized by the state firms, enabling the private sector to exert greater influence on economic transition in China. As a result, private enterprises participated in the restructuring of SOEs and entered previously monopolized sectors in this new phase of privatization. With the increasing significance of private enterprises in the national economy, 1,554 entrepreneurs in the private sector joined the CCP and about 32.2% entrepreneurs of private firms were party members in 2006 (Gao, 2007).

Table 1.1. The private sector outpaces the public sector (percent of value added by firm ownership).

Source: OECD (2005, p. 81).

1.2. The Emergence of Industrial Clusters in China

The formation and growth of industrial clusters has taken place within the context of ownership reform of SOEs and the rapid development of the private economy along the coastal provinces in China. The industrial clusters have played an important role in stimulating the regional development and strengthening the local–global linkage. Some of them have exhibited similar features to those in Italy (Wang, 2011).

Many industrial clusters composed of small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) were first established in the towns and cities in the coastal region, particularly the Pearl River Delta and the Yangtze River Delta along the process of rural industrialization. Different paths of economic growth have emerged known as “the Pearl River Delta Model” (Guangdong province, South China), “the South Jiangsu Model” (Jiangsu province, East China), “the Wenzhou Model” (Zhejiang province, East China) and “the Yiwu Model” (Zhejiang province, East China), stimulating the regional economic development.

The formation of the “Pearl River Delta Model” was attributed to the open-door policy of 1978. In the mid-1980s, the special economic zones in the Pearl River Delta were established and the Township and Village Enterprises (TVEs) in the region had very high outward dependency. With the transformation of their role as processors for joint ventures and solely foreign-funded enterprises, both foreign capital and advanced management practices were introduced to China (Yang, 2007).

“The Wenzhou model” emerged in the 1980s. Wenzhou is a prefecture-level municipality in the southeast corner of coastal Zhejiang province with a population of over six million, covering 11,800 square kilometers including two municipal districts, one inland city and eight rural counties. It is a mountainous area with limited cultivated farm land and poor transportation infrastructure. The initial foundation for industrial development was weak. Rural industrialization in Wenzhou was achieved mainly through thousands of family workshops closely linked to the “Commodity trading markets”. “Small commodities, big markets” is often used to describe the rapid economic growth in Zhejiang province. The commodities used to be mainly daily necessities with small-scale production, limited technology content and lower cost of transport. The formation of industrial clusters in Wenzhou and even the whole Zhejiang province was demonstrated as hundreds of family workshops engaged in the same industry and agglomerated in neighboring villages or towns (Shi et al., 2002; Wei et al., 2007).

The “South Jiangsu Model” emphasized greater enterprise autonomy, but it was based on the predominance of small SOEs and local TVEs that did not follow the radical privatization path of the Wenzhou model. Jiangsu Province adopted a policy to encourage the formation of collective shareholding enterprises in 1995, which required coordination with local governments at a time when disengagement and general privatization was already being propagated in Zhejiang. From 1999 onwards, local governments were required to reduce their control over or shares in collective enterprises and small SOEs by 2002. The industrial clusters in the southern part of Jiangsu province concentrated on labor-intensive, capital-intensive and technology-intensive industries, including synthetic fibers, construction materials, information technology (IT) and the manufacturing of heavy machinery equipment (Wang and Shi, 2006; Wei et al., 2009).

The bottom-up nature of rural industrialization in Zhejiang province resembles industrial clustering in northern Italy (Wang, 2001; Lu and Ganne, 2009). Firstly, the industrial clusters of both Zhejiang and Italy concentrate on light industries such as textiles including socks, clothes and ties. Secondly, although large firms are present in both contexts and are integral to cluster dynamics (Guerrieri and Pietrobelli, 2001; Wang et al., 2007), SMEs are the predominant element both in the Zhejiang province and Italian clusters. In both clusters, these firms are characterized by substantial flexibility and innovativeness (Piore and Sabel, 1984; Becattini, 1990; Guerrieri and Iammarino, 2001; Marukawa, 2009). Thirdly, the industrial clusters in Zhejiang province exhibit the same awareness of the need for innovation, the same preference for initiating family-based businesses and the same spirit for taking risks as those in Italy (Chen, 2000; Wang and Shi, 2006). Moreover, in both countries, the local–global linkages between industrial clusters and international markets have been strengthened through the formation of strategic alliances with foreign firms for technology transfer (Wang, 2001; Pietrobelli, 2004; Gambarotto and Solari, 2005).

Although the industrial clusters in Zhejiang province, East China, match the Italian model to some extent, they have their own unique trajectory of growth and development. The most prominent and distinctive feature of cluster development in Zhejiang province, in contrast to cluster development in Italy, has been the role of local government in deliberately and purposively establishing and developing large-scale “Commodity trading markets”, which have contributed to the linkage with the huge domestic market and overseas business expansion. The research in the Ningbo clothing cluster, the Shaoxing synthetic fiber cluster and the Yiwu socks cluster, all in Zhejiang Province, shows that the local government plays an important role in the formation, development and upgrading of industrial clusters.

1.3. Institutional Change and the Development

of Industrial Clusters

The changes of the past three decades outlined above have attracted considerable research both within China and the rest of the world. This book seeks to contribute to this research, albeit by means of a selective emphasis. Thus, the main objective of this book is to explore the relationship between the complicated interactive process of institutional change and the development of industrial clusters in China. It focuses on how institutional change has led to the formation and development of industrial clusters. Industrial clusters play an important part in regional development in China because it can generate collective efficiency through economic agglomeration, eventually leading to regional innovation and competitive advantage (Bellandi and Lombardi, 2012).

This research has been carried out with institution theory, giving weight to institutional change through multiple case studies of textile and clothing clusters in Zhejiang province, East China. The institutional approach provides one broad framework to study the process of economic transition in general, which is a complex economic and social phenomenon. The micro case studies, which are effective in illustrating the interaction between institutional change and industrial development, have shown that the evolution of political and economic institutions determine the economic performance of transitional economies eventually because they create an incentive structure of the whole society. The evolution of the institutional matrix has had great impact on the formation and growth of industrial clusters in the course of regional development in rural China in transition.

North (1981, pp. 201–202) defined institutions as “a set of rules, compliance procedures, and moral and ethical behavioral norms designed to constrain the behavior of individuals in the interest of maximizing the wealth or utility of principals”. Institutions are routines, habits and social rules affecting the interaction among individuals, including political, economic and social institutions. There are formal institutions such as constitutions, laws, bills of rights, courts, regulations and standards, which form legal and political frameworks for social interactions. In addition, there are informal institutions, such as cultural norms, conventions, codes of conduct, norms of behavior, traditions, habits, attitudes and generally accepted, but informal procedures for governing social interactions (North, 1990).

Institutional changes have played a critical role in shaping the opportunities of actors and in allowing supporting certain types of behavior, while discouraging others (Beckert, 2010). In this book, institution means “a system of socially produced regularities that shape, and are in turn shaped by, individual behaviors” (Kuran, 2010, p. 6).

Institutions possess three basic functions including the reduction of uncertainity, management of cooperation and conflicts, and provision of incentives that influence behavior in human interaction (Edquist and Johnson, 1997). According to Scott (2002, pp. 170–174), “the use of institutional logics, actors and governance structures to examine institutional structures and processes in organizational fields. Institutional logics refer to belief systems and associated practices that are operative in a field. They combine both culture-cognitive and normative elements. Institutional actors, both individual and collective, create, embody and enact the logics of the field. Governance structures operate (e.g., nation-state structures), affecting the field’s structure and activities. Such structures typically combine normative and regulative elements”.

As suggested above, the Chinese government has withdrawn significantly from many parts of the economy although the core public utility and resource-based industries remain in public hands. In the remaining non-core industries that represent more than two-thirds of industrial output, state firms only produce about one-quarter of value added and are subject to competitive forces. Restructuring in the industrial sector has been most rapid, representing 57% of non-farm business sector value added in 2003. In the eastern coastal region (especially Zhejiang, Guangdong and Jiangsu provinces), the share of industrial value added from the private sector is 63% against only 32% in other regions. In manufacturing, foreign enterprise growth was in the electronics and telecommunication equipment sector while they were much less active than domestic enterprises in sectors such as textiles and smelting steel (OECD, 2005). However, the further reform of SOEs makes more room for the expansion of private sector. This does not simply mean the complete state withdrawal and allows the private sector to take over. The general picture in China shows that the rapid growth of private firms in China has been accompanied by frequent changes in ownership, new organizational forms and the structure of property rights.

The growth of private firms has been closely linked to the restructuring of SOEs in the course of cluster development in China. The effective SOE reform has partly depended on the success in carrying out the transition tasks at the critical stage of the growth of private enterprises. When industrial clusters in China are in the process of rapid development and constant upgrading, a lot of clustered firms have inevitably participated in the further restructuring of SOEs or formed alliances with SOEs and foreign-funded enterprises as they pursue the strategy of diversification. Some clustered firms have become listed on the stock exchanges by buying a SOE shell so as to improve their financing capability through the capital market.

The report of the 17th national congress of the communist party of China by President Hu Jintao in October 2007 emphasized the significance of upholding and improving the basic economic system in which public ownership is dominant and different economic sectors develop side by side, unwaveringly consolidating and developing the public sector of the economy, unswervingly encouraging, supporting and guiding the development of the non-public sector, ensuring equal protection of property rights, and creating a new situation in which all economic sectors compete on an equal footing and reinforcing each other. The reform of collectively-owned enterprises was pressed ahead with and various forms of collective and cooperative economic operations will be developed. The development of individually-owned businesses and private companies as well as SMEs were promoted with equitable market access, a better financing environment and less institutional barriers. The central government continued to develop the economic sector with mixed ownership (Hu, 2007).

The local government established many “Commodity trading markets” in the coastal provinces in the 1980s. They were spread to other parts of China throughout the 1990s. The emergence and growth of many industrial clusters have been closely related to the “Commodity trading markets”. They are closely inter-related and inter-dependent. Many “Commodity trading markets” have promoted the growth of industrial clusters while many industrial clusters have, in turn, enlarged the scope and scale of the specialized wholesale markets. With the effective management and administration of the local government, some “Commodity trading markets” have achieved great success and even intern...