![]()

Chapter 1

A Singular Enigma

“We can’t understand the plot of Downton Abbey by taking apart the television.”1

I think, and you think. But how we manage to think is almost a total mystery to science. In sharp contrast to almost every other topic that scientists have tackled, your cleverness remains an enigma despite decades of scientific enquiry. From this book you will find out why your easy skills — such as chatting — have proved so difficult for science to understand. Your cleverness is not easily explained, but by following the scientific probing described in the following chapters you will learn a lot about this accomplishment that makes you unique in the vast tree of life. You will also learn about the nature of scientific enquiry itself.

Because we all think, every reader has a sound basis for assessing what the scientists say about “thinking”. So what do they say?

Alan Turing, the British mathematician rightly famed for his contributions to the cracking of the German Enigma codes in the Second World War, was one scientist who grappled with the notion of “thinking”.

Pushed to an early death at age 41 by the society he had done so much to save, Turing’s fundamental contributions to computer science are less well known outside the world of computing. He defined the abstract model, the Turing Machine, upon which modern Information Technology (IT) still rests. He also constructed a number of fundamental proofs pertaining to the scope and limitations of this technology.

In addition, Turing has a good claim to be the father of the quest to construct IT systems — essentially computer programs — that exhibit intelligence, the field of endeavour known as Artificial Intelligence (AI). Squarely in the middle of the 20th century he conjectured that computers, which hardly existed at the time, might be programmed to play chess and participate actively in other hitherto exclusively human activities.

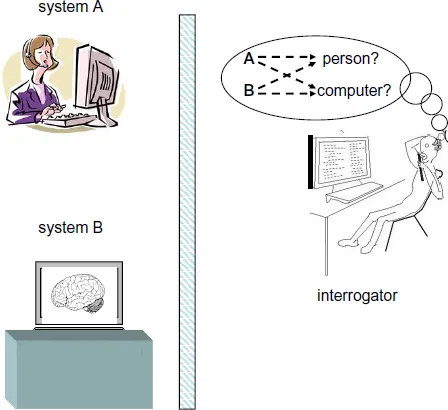

Turing wisely side-stepped the idea of defining what constitutes thinking and instead proposed the Imitation Game, often known today as the Turing Test2. Turing’s idea was that if a person is allowed to engage another unseen “system” (either another person or a suitably programmed computer) in unrestricted dialogue, and consistently mistakes the computer for another person, then it must be conceded that the computer is thinking. Passing the Turing Test is the proposed criterion of “thinking”, in effect a definition of “intelligence”, and is one that has stood the test of time, although it is not without its critics3.

This is how the experiment goes: viewing yourself as the interrogator, your aim is to “spot” the computer system — is it system A or system B? You can ask whatever you like, but the computer system is, of course, under no obligation to be truthful.

A: OK, I’m the person here. Ask me any question and I’ll prove I’m the human.

Interrogator: A, how many fingers on your left hand?

A: Five, of course — well maybe four and a thumb.

Interrogator: B, what do mangoes taste like?

B: I’ve never tasted a mango so I cannot tell you.

Interrogator: Both of you, what’s 282 multiplied by 40?

A: Sorry, I need a calculator for that one. I can’t do sums.

B: Hang on a minute… it’s 11,240.

Within this experiment, you are as qualified as anyone else to play the part of either the interrogator or system A. How would you go about either of these roles? As system A you are aiming to convince the interrogator that you are human and quite distinct from the computer system beside you. Absolutely anything can be said, but what sort of things would you say? You would be trying to project “humanness”4, but what are the signals of that?

You might focus on the various consequences of having a human body or interacting within a community of humans. In both situations, system B (which doesn’t presumably have a human-like body nor live within a human community as a human) might be expected to reveal its artificiality.

Both roles bear much thinking about (as many commentaries on the Turing Test have explored) but produce precious few clear directives. Is system A the person in the above dialogue, or is it system B? A communicates like a human, but B got its multiplication wrong. It’s a tough decision, indeed an impossible one with only a small snippet to go on, because intelligence admits no simple tests (Maxim 2) — a first collision with scientific practice. Hence, the Turing Test requirement of extended dialogue5.

Could jokes be a key? What if the interrogator tells jokes, and then assesses the responses of system A and system B? Will the computer reveal itself by consistently failing to be amused? We don’t know, but it’s a plausible idea because the humour of joke appreciation appears to tap the deep subtleties of word meanings. Ranged against this strategy, an attempted humour probe can be deflected by a response, such as, “Just be serious, I am not in the mood for jokes.” But any such quashing of potential for humour does require some recognition that humour is being attempted, unless launched as a pre-emptive strike. And so the possibilities go on…

It’s an interesting puzzle that any of us can join in. We all have the capacity to engage fully; this central experiment is not the exclusive preserve of experts. Your insights are likely to be as good as anyone else’s.

The underlying assumption of the Turing Test is: if you can hold up your end of a prolonged chat in English, then you must be thinking. This means that you are intelligent. Many scientists hold this to be so. Is it reasonable?

You can talk more or less effortlessly with many people in many different situations. Does this mean that you are always exercising your intelligence whilst chatting away? Apart from your knowledge of the language itself — what can be said and how it can be said — you use your knowledge of the particular situations under discussion, your knowledge of the person you’re talking to, common sense knowledge, and knowledge of the world. That’s a lot of knowledge that must be stored and organized, and integrated into your sentences. So, maybe extended and sensible conversation does imply intelligence? Turing would have it so. Would you?

Turing gave us a definition that we can work with but he was, of course, by no means the first luminary to single out human language as a key indicator of intelligent thought. Early in the 17th century, for example, the philosopher Descartes, famous for “I think, therefore I am”, proposed the human capacity for language as a “means [to]… tell the difference between men and beasts”:

No men are so dull-witted and stupid, not even imbeciles, who are incapable of arranging together different words, and of composing discourse by which to make their thoughts understood; and that on the contrary, there is no other animal, however perfect and whatever excellent dispositions it has at birth, which can do the same.6

Does an ability to chat seem reasonable as a definitive test of basic intelligence, in a word, cleverness? Your hunches are as valid as mine, and similarly not to be relied upon, but that does not mean they are worthless. Such insights do present us all with a basis for examining these elements of a scientific understanding of intelligence, provided we do not take them to be indisputable guides to truth.

Science suggests that extended and diverse dialogue is complex because it must involve management of similarly diverse knowledge. Short-term chit-chat, so the thinking goes, does not. So, how good are the best conversational computers?

This question leads us onto the further sense in which Turing is the archetypal AI man. He predicted that by the end of the 20th century computers would pass his Turing Test on about 70% of occasions. In other words, Turing was confident that half a century of progress with computers and a scientific understanding of intelligence would be enough for the scientists to program computers so that they would be able to chat in English just like you or I. Indeed, the essence of the Turing Test is that the computer’s language abilities should be indistinguishable from yours or mine.

Just like his scientific contributions, this prediction has set a pattern that endures. The Turing Test pass rate is nowhere near 70%. More than 50 years on, and despite unimaginable advances in computer technology (for Turing we might guess), modern computers are still not close to joining in conversation with us. No computer system has come close to passing the Turing Test. Despite decades of scientific analysis of language and careful programming, and despite hundreds of attempts, the Turing Test pass rate is firmly fixed at 0% with no indications that a lift-off into positive numbers is imminent7.

A conversational computer remains elusive. Brief banter delivered by computers, as we shall see, is with us here and now, but extended dialogue ranging through diverse topics is still the sole preserve of humanity. Indeed, the average three-year-old toddler can out-talk any computer system.

Ever since Turing framed his test, the field of AI has been rife with predictions of the breakthroughs to be expected “soon”8. Over the intervening half century or more, the details of this trend have been relentlessly reconfirmed; all such predictions, just like Turing’s, have failed dismally9.

Yet alongside every new demonstration of an IT system that shows the faintest stirrings of what might become intelligent behaviour, we still get confident predictions that the big breakthrough will be soon — as soon as the next steps are accomplished. Such is the prevalence of this ploy that it has a name: hopeware. It’s the anticipated but necessarily hazy successor to the IT system (the software), or the robot10 being discussed or demonstrated. (Hopeware will get its own chapter once we have surveyed a range of examples).

Why is this? A simple, but hardly enlightening, answer is that we the scientists (enthusiastically over-supported by science writers and IT entrepreneurs) have consistently overestimated the speed of development of the pertinent technologies. This has happened primarily because human intelligence has proved (so far, at least) to be a far more complicated, even mysterious, phenomenon than it appears from a distance.

Is over-enthusiastic prediction also due, more fundamentally, to the nature of intelligence? Can a significant part of the cause be an irrepressible urge deep in the genetic make-up of us all?

Every intelligence is uncontrollably over-eager to “see” a like mind operating elsewhere. This human propensity can overthrow objective judgement even for that somewhat fictional character — the cold and rational scientist.

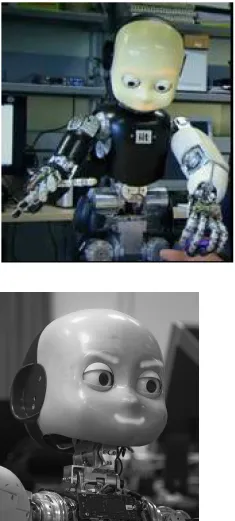

(iCub photo by Lorenzo Natale, IIT, Italy; reproduced with permission)

This is one of the iCub robots. It looks like a human child, it speaks like one, and it can do things that a human child can do. We meet this “toddler robot” in the 2011 UK-TV Channel 4 series11, Brave New World, where we see that it can chat persuasively, it can learn to recognize objects, and it can understand what it is told to do with these objects. In particular, it can reach out and learn to grasp the objects. Other versions of iCub learn to crawl, learn to shoot arrows at a target, and so on.

The iCub robot also has facial expressions to express its supposed moods. All in all it appears on the way to an Artificial Intelligence well in excess of the Turing Test requirement of textual conversation.

Central to the impressive TV demonstration, the iCub was presented with two objects, named as an octopus and a purple car. It followed instructions “to learn” each object using its eyes, and then “to touch the purple car” which it proceeded to do.

Just after “learning” the octopus, it came up with an off-the-cuff comment that smacked of real intelligence.

Unfortunately, immediately after “learning” the second object, the purple car, it apparently could not resist the urge to broadcast its enthusiasm for this object as well.

One spontaneous, apt and non-functional statement of pleasure gives a fillip to our predisposition to “see” intelligenc...