![]()

Part I

System Change and Economic

Transformation

![]()

Chapter 1

System Change in Central and Eastern European Countries and Their EU Integration

In the 21st century the European Union (EU) spatially enlarged itself eastward. In May 2004, eight countries from Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) and two Mediterranean island countries joined the EU. In January 2007 Romania and Bulgaria joined the EU. In July 2013 Croatia joined the EU. The number of the member states increased to 28. With its population of about 500 million, the EU has huge economic power comparable to that of the USA. It is expected that the Western Balkan countries will be admitted to the EU in five to 10 years. However, the global financial crisis in 2008–2009 revealed that the EU has serious problems. The EU, the Eurozone in particular, has been shaken by the Greek crisis, which surfaced in autumn 2009, and the subsequent crises in Southern Europe such as Spain, Portugal and Italy.

Let us consider problems of the European integration, going back in history. Other researchers do not mention it so often, but this chapter1 argues that the USA has been concerned with the European integration as a shadow leading actor. Towards the end of the 1980s when the European Community (EC) tried to deepen the integration further and was about to enter the new stage, system change occurred one after another in Eastern Europe from the mid-1989 through the end of the year. Immediately after the system change there were two approaches, one being French and another American, to the problem of what the future of Central and Eastern Europe would be like. In the end, the American approach was adopted. In the subsequent transition to a market economy in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union, from an objective point of view, the experiences of East Asia, where the state has played a major role in the economic development, could be taken into consideration, but they were neglected. Instead, neoliberal policies were imposed on these transition countries by the US-backed international financial institutions, aggravating the transformational depression. After explaining these points, I will briefly trace the process of the EU’s eastward enlargement.

1. The European Integration and the USA as a Shadow Leading Actor

The history of the European integration dates back to more than 60 years ago. The European integration was promoted by postwar European leaders, who were determined not to repeat a war in Europe, as well as by European people, who supported their policies and made continuous efforts. At the same time, however, it was the USA that played a shadow leading role in the European integration. According to Endo (2013), the integrated Europe designed by Jean Monnet — a founding father of European integration — was based on the power of the US and the Atlantic community. Monnet was well aware that postwar economic rehabilitation in France could not be accomplished only by France. American funds were vitally important for postwar economic reconstruction in Western Europe. It was the OEEC (Organization for European Economic Cooperation) that served as an organization for receiving and allocating American funds. German coal was necessary for production of iron and steel in France. At the same time, of course, there was lofty spirit. From the standpoint of pan-Europeanism, Jean Monet thought the union of France and Germany, both of which have often fought each other in the past several centuries, connected by common economic interests would make it impossible for them to trigger a war on the European continent. Accepting his idea, French Foreign Minister Robert Schuman published a declaration in which he proposed economic integration in 1950. Thus the European Community for Steel and Coal (ECSC), which placed steel and coal under joint control, was established by the Paris Treaty in 1951. Based on this experience, in January 1958, the European Economic Community (EEC) started, with France, Germany, Italy and Benelux as the original members. The EEC aimed to create a common market by establishing common external tariffs and by gradual reduction of internal tariffs.

As long as the logic of the Cold War and the hegemony of the US were valid, Western Europe continued to rely on the US-led NATO for its security, even after the inflow of American funds became unnecessary. Within such a framework, Europe pursued integration with its geographical territory limited to the Western part and its functional field limited to the economy. Although not well known outside Europe, with the protection of human rights as its main duty, the Council of Europe (CoE) has been trying to guarantee Europe’s originality in the sphere of social rights and local autonomy. There existed a compound international regime which could be called “the EU–NATO–CoE regime” (Endo, 2013, pp. 185–186).

In 1966, integrating with the ECSC and the EURATOM (European Atomic Energy Community), the EEC transformed itself into the European Community (EC). Later, with an increase in the number of member countries, the EC expanded spatially. In the 1980s, the West European economy was stagnating in the face of a sharp increase in the import of industrial products from the USA and Japan. In order to overcome such a situation, leading figures of the European business circles rallied across borders. They stressed the necessity for creating a huge economic space in which large enterprises could enjoy the economy of scale by establishing a single market, thereby improving their competitiveness. With this discussion as a background, in 1986 the Single European Act was adopted, which would abolish non-tariff barriers and create a huge economic space so as to encourage emergence of giant companies which could compete with their US and Japanese counterparts. At the same time, the efforts for creating a single currency continued. Using such a sense of crisis as a springboard, the EU member countries have continuously strengthened the European integration (Tanka, 2006). The process of strengthening the European integration while transferring part of the state sovereignty to the EU is called “deepening of the integration”. The Maastricht Treaty of 1992 as well as the start of the EU in November 1993 was an extension of such “deepening of the integration”. On the way to the Maastricht there occurred dramatic changes in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union from 1989 through 1991.

2. Collapse of Socialism and Return to Europe

In the 1960s, relations between the EC and the Comecon (Council for Mutual Economic Assistance; in practice it was a socialist version of the economic integration on the basis of the central planning economic system) were very weak. As soon as Willy Brandt, the top leader of the Social Democratic Party in West Germany, took office as the Chancellor in 1969, he embarked on the eastward diplomacy actively, and the tensions between the East and the West became relaxed gradually. The détente culminated in the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE) held in Helsinki in 1975. It was the biggest harvest for Moscow as the status quo in Europe was confirmed in an official document. In order to recover from a lag in technology, the Soviet Union and East European countries made their efforts to increase trade with the Western countries. In the 1970s all East European countries (except for Albania) pursued industrialization with priority given to heavy and chemical industries. They made equipment investment actively with loans from the Western countries. According to leaders’ intention, they could repay the loans if the equipment began operation and the products were exported to the Western markets. The Soviet Union and East European countries did not experience the first oil shock as seriously as the Western industrialized countries. The oil shock led the Western industrialized countries to shift their emphasis to high-tech industries whereas East European countries continued industrialization with priority given to heavy and chemical industries as before because they enjoyed cheaper oil2 supplied by the Soviet Union (however, the former Yugoslavia was supplied oil by a partner nation, Iraq). In the second half of the 1970s in East European countries, especially in Czechoslovakia, Poland and Hungary, the economic growth rates decreased remarkably. Industrial products made in East European countries were not competitive on the world market, and it was difficult for these countries to increase the exports of their products. In the second half of the 1970s, due to recession, Western industrialized countries reduced their imports from East European countries. By the end of the 1970s the external debts of these countries greatly increased, gradually leading to their economies in stalemate. At last, the Polish economy recorded negative growth in 1979. In the 1980s the East European economies stagnated, showing signs of crisis towards the end of the 1980s.

In the early 1980s when the world oil price decreased (i.e., the reverse oil shock), a delay in the modernization of the Soviet economy also surfaced. According to Mikhail Gorbachev, the Brezhnev period (1964–1982) was “the period of stagnation”, and the end of his period was “on the brink of a crisis”. In March 1985 Gorbachev took office as the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, and the next year he started a fundamental reform called “Perestroika”. In December 1984, four months before his inauguration to the General Secretary of the Party, in the capacity of chairman of the foreign affairs committee of the Soviet Union’s Supreme Council he visited the UK. In his speech at the British Parliament, he said “Europe is our common home. It is a home, not a war-dominated territory”. In his speech at the East Germany’s Party Congress in April 1986, he mentioned “from the Atlantic to the Urals” and stressed the Soviet Union being a member of Europe. In the second half the 1980s Gorbachev continued to call for disarmament of the East and the West with “a European Common Home” as a keyword (Kawaraji, 1993). There was great progress in the normalization of relations between the Comecon and the EC. The general assembly of the Comecon held in 1984 confirmed that it was ready to conclude an agreement on the normalization of relations with the EC. In 1985 Gorbachev said that the Soviet Union and East European countries as a group were ready to recognize the EC. In 1988 a joint statement by the EC and the Comecon was announced in Luxembourg (Tanaka and Matsunaga, 1990, p. 98). G7’s Arche summit in July 1989 decided to support Poland and Hungary, where reforms had just begun, and gave the European Commission power to coordinate the assistances. This was PHARE (the initials of Polongne, Hongrie, Assistance a la Restructuration Economique) Program by G24 (the conference of 24 countries for supporting Eastern Europe), and it was originally designed to support strongly both countries’ efforts for building democracy and a market economy.3 In December 1989 the summit talk of the USA and the Soviet Union held in Malta Island declared the end of the Cold War.4

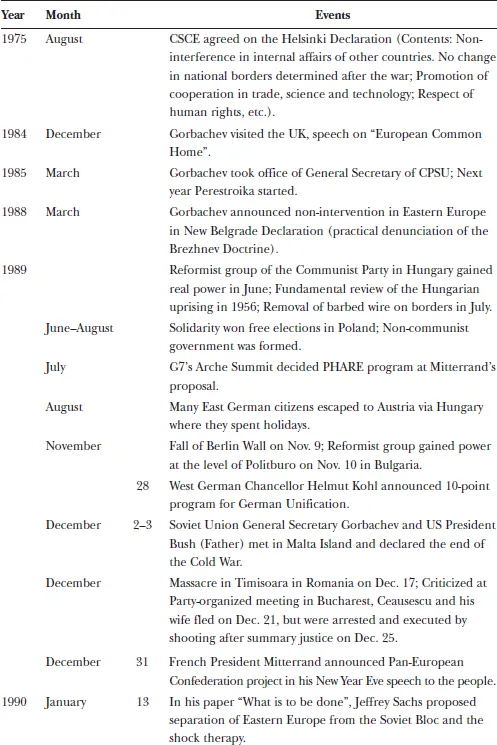

From 1989 through 1991, as mentioned above, socialism collapsed, followed by the transition to a market economy in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union. However, almost nobody could predict that the collapse of socialism occurred as a result of a domino effect exactly at that time, i.e., from the mid-1989 to the end of the same year. In spring 1990 free elections based on a multi-party system were conducted in East European countries one after another, and capitalism-oriented parties won in all the countries, determining the course toward the transition to capitalism (see Table 1-1).

After the system change, East European countries strongly expressed their aspirations for “Back to Europe” (Henderson, Karen, ed., 1999), namely membership of the European Community. The EC member countries were perplexed with these countries’ aspirations for joining the EC. As mentioned above, 12 member countries of the EC had been concentrating their efforts on formation of consensus about the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) from 1988 through 1990. In addition, from 1989 through 1992, five EFTA (European Free Trade Association) countries, i.e., Austria, Sweden, Finland, Norway and Switzerland, applied for EC membership one after another5 (in the end, these countries except Norway and Switzerland were admitted to the EU in 1995). The existing EC member countries were suddenly faced with the choice of giving priority to deepening of integration or enlargement.

Table 1-1 Chronology of the System Change in Eastern Europe

Source : Compiled by the author.

3. Two Approaches: French vs. American

3.1 French Approach

This conception was suddenly unveiled to the world by President Mitterrand in his New Year’s Eve address (December 31, 1989) to the French people (Gowan, 1995). This was a noteworthy and grand vision about the future relations between the Western Europe and quickly changing Eastern Europe.6 Based on Bozo (2008, p. 396) and Gowan (1995, p. 6), Mitterrand’s project of European Confederation can be summarized as follows:

(1)Encouraging the former Comecon region, including the USSR, to remain linked together economically.

(2)Leaving the evolution of socio-economic forces in each country to the interplay of forces within the country concerned, without using Western pressure to impose a particular system.

(3)These countries would probably move toward some mix between socialism and capitalism. Eastern Europe would nevertheless grow closer to an increasingly integrated Western Europe, thereby making it possible progressively to overcome the East–West (and Germany’s) division, at least in concrete terms.

(4)Making the emphasis of Western policy that of economic revival in the region as a whole, using, for example, a regional development bank for that purpose ( EBRD which was to be established in 1991).

(5)Rejecting the perspective of bringing some ex-communist countries into the EC in the short or medium term. Instead, offering a pan-European confederation embracing both the EC and the East, including the USSR.

It seems that Mitterrand envisaged the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE) as an institutional framework. The CSCE, which included both the US and the Soviet Union and for nearly two decades had been France’s preferred vehicle for East–West change, was of course seen as essential, but it had limits. French diplomats were wary of a blurring of the role of the Atlantic alliance and, worse yet, of nascent European strategic identity (Bozo, 2008, p. 396). The prospective institutional framework was not clear at this stage.

Although there was a difference in their political standpoint between conservative Charles de Gaulle7 and socialist Francois Mitterrand, in the domain of diplomacy the latter inherited the former’s position. Mitterrand advocated “Europe from the Atlantic to the Urals”8 which was reminiscent of “Europe from the Pyrenees to the Urals”, a famous expression by ex-President Charles de Gaulle (1958–1969). It may sound an unrealistic idea, but prior to Mitterrand’s proposal there were some developments in the Soviet Union: Gorbachev’s inauguration to General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in March 1985, Perestroika and new-thinking diplomacy starting in the next year, Gorbachev’s conception of “European Common Home”, and mutua...