- 632 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Developing Countries In The World Economy

About this book

Differences in the choices of trade and macro policies, both by developing countries and by developed countries towards developing countries, have been critical in determining the overall performance of developing countries. All too often, the performance of developing countries has not been assessed using appropriately conducted studies. The papers in this book are chosen to bridge this gap and show how a quantitative approach to policy evaluation can help resolve controversies and explain the choice of observed policies.

The book brings together carefully selected papers that assess the impacts of various trade and macro policies, by quantifying the policies of developing countries at the macro level (exchange rate, investment, savings) and at the sector level (trade and industrial policies), in addition to policies of developed countries towards developing countries (trade preferences, quotas, VERs and migration policies). Facets of the political economy of trade, migration, and climate policies are explored (such as the enlargement of the EU, the rise of regionalism and how it can ease the pains of adjustment to trade liberalization, openness and inequality). Growing tensions between trade and the environment are also investigated. In short, this book covers a wide area of events ranging from external and internal shocks to external and internal policies, showing how the consequences of these events can be brought to rigorous quantitative analysis.

Differences in the choices of trade and macro policies, both by developing countries and by developed countries towards developing countries, have been critical in determining the overall performance of developing countries. All too often, the performance of developing countries has not been assessed using appropriately conducted studies. The papers in this book are chosen to bridge this gap and show how a quantitative approach to policy evaluation can help resolve controversies and explain the choice of observed policies.

The book brings together carefully selected papers that assess the impacts of various trade and macro policies, by quantifying the policies of developing countries at the macro level (exchange rate, investment, savings) and at the sector level (trade and industrial policies), in addition to policies of developed countries towards developing countries (trade preferences, quotas, VERs and migration policies). Facets of the political economy of trade, migration, and climate policies are explored (such as the enlargement of the EU, the rise of regionalism and how it can ease the pains of adjustment to trade liberalization, openness and inequality). Growing tensions between trade and the environment are also investigated. In short, this book covers a wide area of events ranging from external and internal shocks to external and internal policies, showing how the consequences of these events can be brought to rigorous quantitative analysis.

Contents:

- Reforms, Adjustment and Growth:

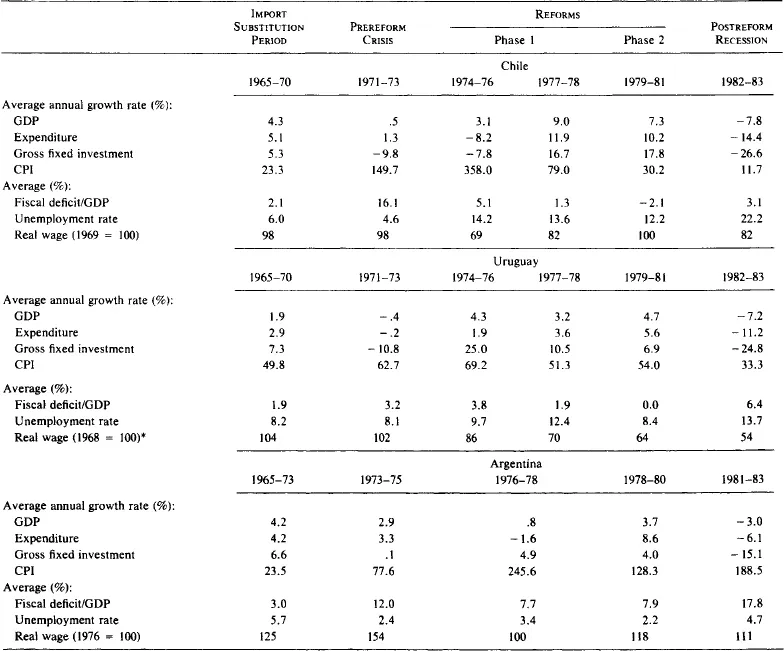

- What Went Wrong with the Recent Reforms in the Southern Cone (with Vittorio Corbo and James Tybout)

- The Effects of Financial Liberalization on Savings and Investment in Uruguay (with James Tybout)

- Adjustment with a Fixed Exchange Rate: Cameroon, Côte d'Ivoire and Senegal (with Shantayanan Devarajan)

- Growth-Oriented Adjustment Programs: A Statistical Analysis (with Riccardo Faini, Abdelhak Senhadji and Julie Stanton)

- Adjustment, Investment and the Real Exchange Rate in Developing Countries (with Riccardo Faini)

- Fiscal Spending and Economic Growth: Some Stylized Facts (with Céline Carrère)

- Trade Policies, Market Structure and Market Access:

- Pricing Policy Under Double Market Power: Madagascar and the International Vanilla Market (with Marcelo Olarreaga and Wendy Takacs)

- The Influence of Increased Foreign Competition on Industrial Concentration and Profitability (with Shujiro Urata)

- The Effects of Trade Reforms on Scale and Technical Efficiency: New Evidence from Chile (with Vittorio Corbo and James Tybout)

- Do Exporters Gain from VERs? (with Alan Winters)

- Are Different Rules of Origin Equally Costly? Estimates from NAFTA (with Céline Carrère)

- Has Distance Died? Evidence from a Panel Gravity Model (with Jean-François Brun, Céline Carrère and Patrick Guillaumont)

- Political Economy:

- The New Regionalism: A Country Perspective (with Arvind Panagariya and Dani Rodrik)

- The Protectionist Bias of Duty Drawbacks: Evidence from Mercosur (with Olivier Cadot and Marcelo Olarreaga)

- Why OECD Countries Should Reform Rules of Origin (with Olivier Cadot)

- The Political Economy of Migration in a Ricardo–Viner Model (with Jean-Marie Grether and Tobias Müller)

- Attitudes Towards Immigration: A Trade Theoretic Approach (with Sanoussi Bilal and Jean-Marie Grether)

- The Political Economy of Migration and EU Enlargement: Lessons from Switzerland (with Florence Miguet and Tobias Müller)

- Challenges Ahead — An Inclusive Globalization and Environmental Policies:

- Openness, Inequality and Poverty: Endowments Matter (with Julien Gourdon and Nicolas Maystre)

- FDI, the Brain Drain and Trade: Channels and Evidence (with Artjoms Ivlevs)

- Trade in a 'Green Growth' Development Strategy: Issues and Challenges

- Unravelling the Worldwide Pollution Haven Effect (with Jean-Marie Grether and Nicole Mathys)

Key Features:

- One of the few books that addresses the performance of developing countries through appropriately conducted studies with rigorous quantitative analyses

- Adopts a quantitative approach in evaluating policies and shows how this can help resolve controversies and explain the choice of observed policies

- Analysis of the policies in developing countries is done across the macro level and sector levels, as well as on the policy choices of developed countries towards developing countries

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

Reforms, Adjustment and Growth

What Went Wrong with the Recent Reforms in the Southern Cone

I. Introduction

II. The Reforms and Their Intent1

A. Liberalization Policies

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Credits

- About the Author

- Preface and Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I: Reforms, Adjustment and Growth

- Part II: Trade Policies, Market Structure and Market Access

- Part III: Political Economy

- Part IV: Challenges Ahead — An Inclusive Globalization and Environmental Policies

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app