![]()

| Introduction to Flavonoids and Chemoprevention* | 1 |

The use of plant materials to treat human diseases can be found throughout history and is documented in the ancient texts of China, Egypt, and India. In ancient China, the best recognized, earliest work was authored in approximately 2700 BC by Emperor Shen Nung, who is often referred to as the father of Chinese medicine.1 He is credited with tasting 365 herbs and classifying them in part, on their relative toxicity. Many Chinese herbal medicines that are currently used can be traced to the work of Emperor Nung. In ancient India, the system of medicine known as Ayurveda, is thought to have originated between 1500 and 2000 BC.2 Ayurveda texts cite 6,000 medicines which are primarily plant-based to be used for the treatment of a variety of ailments and diseases. Traditional Ayurvedic medicines are polyherbal and contain combined mixtures of plant extracts that are thought to interact synergistically. Approximately 15,000 medicinal plants in India have been documented, but the full identification of medicinal plants and their potential therapeutic value is still thought to be incomplete. Ongoing research efforts focused on identifying active pharmacological components of these herbal mixtures have discovered the integral role that flavonoids play in these ancient recipes.

Another important source of traditional medicine can be found by exploring the history of Egypt. The earliest text from ancient Egypt that describes 829 prescriptions for disease treatment is the Ebers papyrus and is thought to have been written in 1500 BC.3 These primeval treatments that were used by the Egyptians of that time were obtained primarily from plants and trees, but also utilized other substances that were obtained from animal sources including pig eyes. The prepared remedies were taken orally or were applied externally as poultices or unguents. The Egyptians also developed crude methods for delivering vaporized medicine. One method required the use of a double pot. The liquid remedy was poured into a hot pot. A second pot that contained a hole was then placed on top. A straw was inserted into the hole and the patient breathed the vaporized substance through the straw. A second approach involved laying the herbs onto hot bricks. This would release the alkaloid-containing active ingredients of the plant as vapor. Our current labeling of prescription vials is thought to originate from the practice of Egyptian physicians who would often write their prescriptions on small labeled containers which resembled small cylindrical pottery vases. Like Ayurvedic medicines, those of ancient Egypt often contained complex mixtures of herbs. The transfer of knowledge of these ancient medicines was aided by both extensive trade routes and religious practices including pilgrimages and the Crusades. Many of the European monasteries served as repositories of the medical knowledge obtained from these ancient sources where their therapeutic approaches were implemented and refined.

Our current interest in these plant-based medicines that have rich origins in China, India, and Egypt stems from our desire to procure their health benefits in a manner that is both safe and effective. Consumption of herbal medicines is growing worldwide as they are used not only as therapies to cure specific disease states but also as supplements taken with their prescribed “western” medicines. With the advent of modern pharmacological practice, active research has focused on identifying the bioactive ingredients of these traditional herbal preparations, their pharmacological mechanisms of action, their efficacy, and their potential adverse effects. The primary bioactive chemical constituents of plants used for medicinal properties are flavonoids and proanthocyanidines (oligomers of flavonoids), tannins, terpenoids, resins, lignans, alkaloids, forocoumarines, and naphthodianthrones.4 In many cases, the pharmacological activity of the traditional medicines varies considerably and thus these medicines are used to treat a wide range of disease states. For example, flavonoids, terpenoids, and resins are highly valued for their anti-diarrheal properties, whereas alkaloids and terpenoids hold promise for their potential for combating malaria.5,6 Our scientific investigations probing the therapeutic benefits of flavonoids can be traced to experiments on vitamin “P,” a flavonoid preparation isolated from citrus fruit which was found to protect against radiation-induced injury and lethality.7 This early work provided the foundation for the current investigations into the role of flavonoids in providing protection against chronic disease states including diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and cancer, protection which is often attributed to their anti-oxidant and/or anti-inflammatory activities.8,9 Over the past 20 years, typical experimental paradigms have involved administering varying concentrations of isolated flavonoids to either cultured cancer cells or to laboratory animals, followed by the evaluation of cancer-relevant endpoints. Upon accumulation of sufficient evidence supporting their ability to inhibit key biological markers in the absence of adverse effects, clinical phase I trials in human subjects are then initiated. Given that flavonoids are present in relatively high concentrations in many foods and beverages, additional evidence pertaining to their potential health benefits can also be accrued using epidemiological approaches. However, as we attempt to extrapolate findings obtained using isolated, individual flavonoids to develop effective therapeutic and/or chemopreventive agents, we should be mindful of a major tenet of the ancient healers, that individual components may interact synergistically and thus as stated by Aristotle, it may be that “the whole is greater than the sum.”

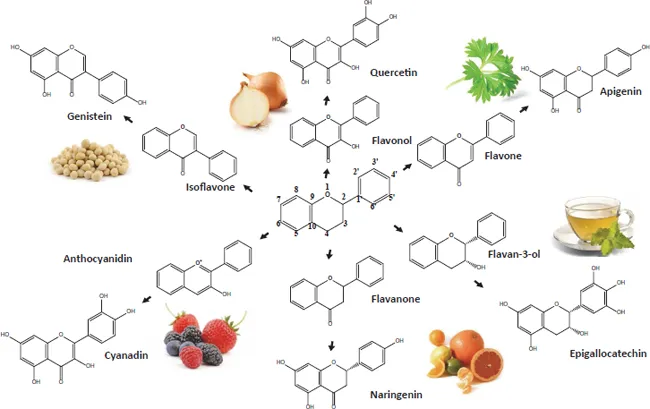

As a first step toward understanding how flavonoids may exert their chemopreventive properties, we turn towards examining their chemical structures (Fig. 1.1). The basic chemical structure of flavonoids has been described as C6-C3-C6; that is, two aromatic rings that are connected by a three carbon bridge.8 The classification of flavonoids is based on their chemical structures which vary in the number of double bonds, the number of oxygen-containing substituents and their relative positions. There are six classes of flavonoids: (1) flavanones, (2) flavonols, (3) flavones, (4) isoflavones, (5) flavan-3-ols, and (6) anthocyanidins. The basic structure of these flavonoid classes is shown in Fig. 1.1. In plants and upon consumption of plant products, these basic structures often undergo further modification which involves their hydroxylation, methoxylation, or O-glycosylation of the hydroxyl groups.10 In addition, the carbon atom may be glycosylated and additional alkyl groups may be covalently attached. The presence of isomeric forms of flavonoid aglycones and the varying patterns of glycosylation often present challenges in the ability to accurately identify and quantify flavonoids in plant-derived food. Further, metabolism by the host organism and its microbiome results in additional modifications that typically include formation of conjugates (i.e., methyl, sulfates, and glucuronides) that often alter the biological property of the flavonoid. Many of these flavonoids harbor intensely studied anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-tumor activities as will be discussed in more detail in subsequent chapters.

Fig. 1.1 A scheme of the six classes of flavonoids and representative flavonoids commonly found in foods and beverages

Human consumption of flavonoids varies depending on global locale, age, gender, socio-economics and dietary preferences. Estimates obtained from a number of studies indicate that the average daily intake in the majority of the global population ranges from approximately 180 to 200 mg.11–14 Tea, fruit, and wine are the major food sources of flavonoids of most population groups. Amongst the most highly consumed flavonoid subclasses are the flavanones and flavano-3-ols.13,15 However, the flavonoid levels as well as the relative amounts of the individual flavonoid compounds within dietary sources can vary significantly depending on the cultivar of plant species, their growth conditions, and the preparation and storage of the food product. Flavonoids representing each subclass and their common food sources are shown in Fig. 1.1.

Flavanones. Some of the best characterized flavonones are hesperidin and naringenin which are highly abundant in citrus fruits.16 Naringenin is well known for its bitter taste and its ability to impair drug metabolism. Thus, consumption of foods high in naringenin, such as grapefruit juice, is often involved in drug-supplement interactions that arise from the inhibition of drug clearance and inappropriately high drug plasma levels. Other flavanones of interest include pinocembrin (5,7-dihydroxyflavanone) found in plants such as Eucalyptus17 and aglyca which is thought to contribute to the anti-inflammatory properties of willow bark.18

Flavonols. The most important contributors of flavonols are thought to be quercetin, kaempferol, myricetin and isorhamnetin which are found in high concentrations in berries.8,19 Quercetin is also abundant in the skins of apples and onions.20 Rich sources of kaempferol include tomatoes,21,22 carrots, tea,23 currants,19 onions,24 cucumber, mustard, coriander, watercress,25 and broccoli.16 Other flavonols of interest include wogonin (5,7-dihydroxy-8-methoxyflavone), a constituent of S. baicalensis, a perennial herb that is used in traditional Chinese medicine,26 as well as rutin and nobiletin found in citrus fruits.27

Flavones. Well-characterized flavones include apigenin and luteolin which are found in relatively high concentrations in food sources such...