![]()

Chapter 1 Major Genres, Characteristics

and Formation of Classical

Chinese Gardens

Classical Chinese gardens may be classified from many different perspectives. Take their geographical features, for example. Chinese gardens can be categorized into northern gardens(北方园林), southeastern gardens(江南园林), and southern garden(岭南园林). In a more common approach, however, based on their characteristics as a whole, gardens are grouped into the following four categories — namely — royal gardens, literati gardens, monastery gardens, and natural country gardens. This classification essentially covers the major forms of classical Chinese gardens.

1.1 Traditional Chinese Imperial State and China's Classical Royal Gardens

Royal gardens are the most distinguished among classical Chinese gardens. The Summer Palace in Beijing, Beihai Park in Beijing, and Chengde Summer Mountain Resort(承德避暑山庄) are all typical works of royal gardens that people are familiar with. What are the cultural and artistic characteristics of Chinese royal gardens?

1.1.1 Royal Gardens and the Establishment and Continuation of Traditional Chinese Unified State

The royal gardens, including the Summer Palace that we now have, were essentially built after Emperor Qianlong's reign in the Qing (Ch'ing; 1644-1911) Dynasty (mid-18th Century). That is to say, they were works of the late Chinese imperial society. These later works are quite different from the earlier works along the development of royal gardens for thousands of years. They do, after all, resume the traditions of royal gardens in some fundamental ways.

Whether in terms of cultural implications or in terms of artistic style, the characteristics of Chinese royal gardens are directly related to the institutional forms of the Chinese imperial society. To a certain degree, we may even say that the royal gardens are but an artistic form of the imperial political structure and the imperial system theory. As you may know, Chinese imperial society reached the zenith of world cultures of its times during ancient China, but it was left further and further behind the tides of the modern world. One of the major reasons for such a brilliant achievement is attributed to China's sophisticated unified imperial system (and relevant political structure and social organization) established since the Qin (Ch'in; 221-206 B.C.) and Han (206 B.C.-220 A.D.) dynasties. Simply put, the basic principle of this system is that all elements of the greater state, including the political, economic, administrative, legal, religious and correspondent cultural patterns, must be constructed and operated around the core of the imperial power. The imperial power is, just as summarized in the Records of the Grand Historian·the Basic Annals of the First Emperor of the Qin: “All the affairs of the empire, great and small, are decided by the emperor.”3

The establishment of such a political system endows the imperial state with a series of important institutional systems, which has directly affected the style and appearance of royal gardens. One example is the unified political model as well as the geographical concept that the royal family owns the vast world. As we know, prior to the Warring States Period (403-211 B.C.), the definition of the “world” for the Chinese was very narrow. At that time there was merely the concept of ethnicity (since the Zhou Dynasty (1046-256 B.C.) was still surrounded by many dispersed independent ethnic states in addition to several kingdoms), but the concept of “unity under heaven(天下一统)”4 was non-existent. Things were completely different later. Ever since the Warring States Period, inspired by the unprecedented discoveries in astronomy and geography, the expansion of transportation, and the rapid increase of political and diplomatic exchanges between vassal states, the concept of time and space had been significantly developed. One of the specific signs for the development was the establishment of a distinct geographic pattern, that is, an unprecedented huge world space with China as its core and the “Greater Nine States(大九州)”5 as its extension. Meanwhile, this geographic pattern formed an integrated unity with the astronomical patterns in the minds of the people. The fulcrum of this unprecedented, huge universe was the unified imperial state established after Qin (Ch'in; 221-206 B.C.) and Han (206 B.C.-220 A.D.) dynasties. The leading position of the imperial power in China's traditional “universe pattern” was thus strongly emphasized for the first time.

Figure 1-1 Restored bird's-eye-view map of the main building complex of the Jieshi Palace(秦碣石宫) in Qin (Ch'in; 221-206 B.C.) Dynasty, and the east and west guard posts in Suizhong, Liaoning6

Qin Shihuang (260-210 B.C.) built a large number of palaces around. His architectural philosophy was to take the massive landscape architecture as a symbol of his empire, Take this palace he built along the Bohai Sea, for example. The palace stretches almost fifty kilometers long from Qinhuangdao (Island), Hebei Province to Suizhong County, Liaoning Province. Its wide guard-post avenue extends all the way to the sea, with a group of immense natural reefs as the guard-post gate for the entire palace. This design embodies the political concept of “encompassing the world”(囊括四海) for the unprecedented unity of the imperial empire and the requirements for fully integrating this concept into the art of the royal garden.

Figure 1-2 One of the forty Yuanmingyuan(圆明园) scenes: “Jiuzhou Qingyan(九州清晏)”

“Jiuzhou Qingyan” is one of the largest major scenic spots in Yuanmingyuan. In 1709, Emperor Kangxi (1654-1722) wrote down the two characters of “Yuanming” on the plaque for the central hall of this scenic spot, marking the beginning of the history of Yuanmingyuan. Illustrated in this picture above is how it appeared in the earlier years of Qianlong's reign. Emperor Qianlong (Chien-lung; 1711-1799) once explained that the design philosophy of “Jiuzhou Qingyan” originated from the universe pattern of the Warring States philosopher Zou Yan (Tsou Yen; 305-240 B.C.), namely, “small seas” are outside of the nine states and are surrounded by larger waters of endless oceans(大瀛海). It thus follows that, on a more profound cultural level, the world pattern and the universe patter established during the Warring States Period, Qin (Ch'in; 221-206 B.C.) and Han (206 B.C.-220 A.D.) dynasties have laid the foundation for the space framework of gardens.

1.1.2 The Sophistication of the Traditional Chinese Universe Pattern and the Establishment of the Spatial Layout of Royal Gardens with Landscapes as the Framework

The establishment of the above-mentioned universe pattern after the Warring States Period (403-211 B.C.), Qin (Ch'in; 221-206 B.C.) and Han (206 B.C.-220 A.D.) dynasties, is concretely presented via visual images of a series of gardens and architecture. Take for example the design and planning of the capital city of the Great Empire (Chang'an) which simulate and resonate with the ideal celestial pattern. Another example is the popularity of “Penglai Myth(蓬莱神话),” originated in the coastal region of the Qi with people's growing interest in everything about the ocean after the Warring States Period. Its popularity rapidly took over the previous “Kunlun Myth.” Such changes of people's worldview and beliefs had a direct impact on the development of gardens. This is because prior to the Warring States Period, people, out of their beliefs in the Kunlun Myth, regarded majestic mountains and terraces replicating high mountains as places of sublime divinity. Constructing numerous huge terraces and placing palaces on top of them, therefore, became popular for palace design among vassal states. Up till this day, earthen terraces and even terrace complexes of several meters or even over ten meters high still remain among the ruins of the old city of Qi in Linzi, Shandong, the ruins of Houma Palace in Shanxi, and the ruins of Zhao Kingdom in Handan. Their magnitude is still staggering (the remaining height of “Huangong Terrace(桓公台)”7 in the old city of Qi in Linzi, for instance, is 14 meters, stretching 86 meters from south to north), whereby one can imagine the aesthetic fashion two thousand years ago valuing grand terraces for palace architecture. Nonetheless, due to people's yearning after the Warring States period for the sea and the rise of the “Penglai Myth” which was closely related to the sea, the previously popular palace architectural style of enormous terraces gave way to people's enthusiasm for, and imitation of, the sea. Qin Shihuang (260-210 B.C.), for example, diverted the Wei River into the national capital, creating the garden pattern of vast waters surrounding an island (which symbolizes the legendary islands of Penglai and Yingzhou). While building the palace in Chang'an, Emperor Wu of Han (Han Wudi; 156-87 B.C.) had the “Kunming Pool(昆明池)” and “Taiye Pool (太液池)” trenched to imitate the sea, and huge artificial hills built like the “Jiantai (渐台)” with a height of six meters in the pool to reproduce legendary mountains at the sea.

Ever since then, “mountains among seas” has become characteristics of the Chinese royal garden landscape system, which remained so up till the Ming (1368-1644) and the Qing (Ch'ing; 1644-1911) dynasties. This type of landscape formation — with natural or artificial landscapes as the framework and rich varied structures as supplementary sceneries — has thus become the essential pattern of Chinese royal gardens as well as other major types of gardens.

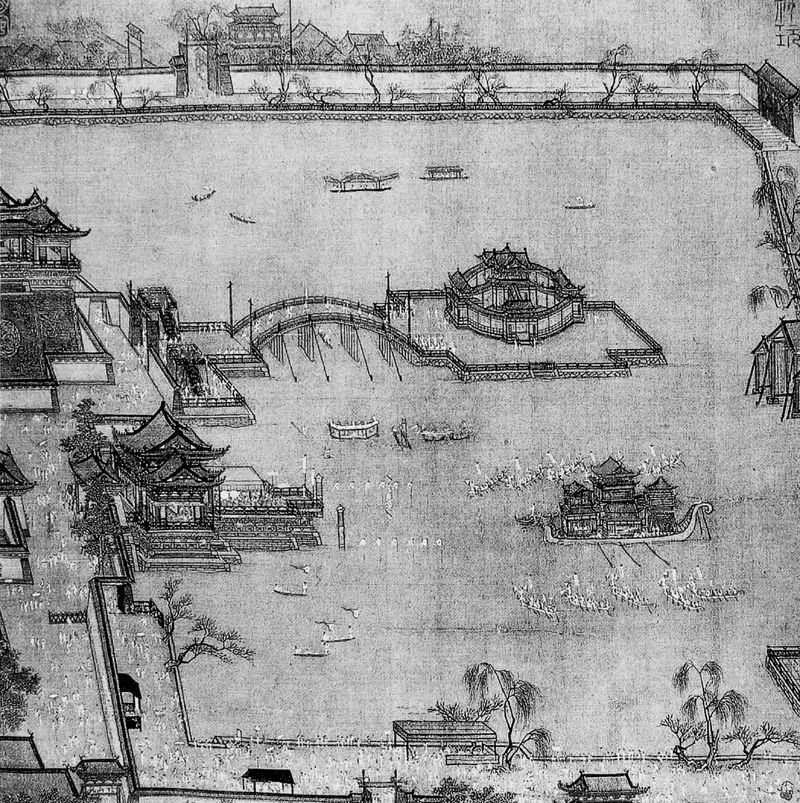

Figure 1-3 (Allegedly·Northern Song/Sung): Dragon Boat Regatta on Jinming Pool(《金明池夺标图》)

From this piece of famous art work, it is clear that the Northern Song (Sung) Dynasty (960-1127) royal garden still retained the tradition of palaces since the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.-220 A.D.), constructing an island (or terrace) in a large body of water. It is also clear that in the Northern Song (Sung) Dynasty (960-1127), majestic structures tower over the royal gardens; structures on the land and in the water form a mutual constructive relationship, echoing and complementing each other in terms of scale and style.

Figure 1-4 The body of water, mountains and towering building complex in the main scenic spot of the Summer Palace

A combination of the vast water surface and enormous volume of the mountain forms the essential framework of the complex landscape system of the royal garden. The expansion and variation of the spatial layout of the water body and the mountains provide the foundation for the interspersed arrangements of a variety of architectural and landscape complexes.

In addition to the above-mentioned facts, Chinese royal gardens present other distinct features either in terms of cultural conception or in terms of gardening art. In order to fully represent the hierarchical order of the imperial state and the infinite majesty of the imperial power, for instance, the main attractions of royal gardens feature splendor and magnificence in general. Furthermore, the axis for the scenic spots and landscape complexes is also very prominent. The above-mentioned “Jiuzhou Qingyan” scenic spot and “Fanghu Shengjing(方壶胜境)” scenic spot in Yuanmingyuan, and the building complex of the Summer Palace on the Front Hill main axis, for instance, thereby make the leading position of the core scenic spots very prominent over other areas in the entire garden.

In terms of artistic technique and decorative style, royal gardens also have distinct features. The colors for all sorts of sceneries in the gardens (architectural buildings in particular), for instance, are typically bright and affluent. Furthermore, there was the institutional system that

Of all that is under Heaven,

No place is not the King's land;

And to the farthest shores of all the land,

No man is not the King's subject.8

Figure 1-5 The main building complex in the Summer Palace

The central axis of the Front Hill building complex of the Summer Palace is very austere and vigorous, thus becoming the core of the entire garden. On this axis, along Kunming Lake, respectively distribute a cluster of large structures, including “Yunhui Yuyu Memorial Arch(云辉玉宇牌坊),” “Paiyun Gate(排云门),” “Paiyun Hall(排云殿),” “Dehui Hall(德辉殿),” “Tower of Buddhist Incense(佛香阁),” and “Wisdom Sea(智慧海).” Several core buildings among this cluster of structures are covered with yellow glazed tile roof, rising floor by floor up along the hill. Such a strong architectural language highlights the sublimity of the royal palace with its splendor, magnificence, domination, and hegemony. As the extension and expansion of these core structures, several secondary buildings are covered with the two-colored green and yellow glazed tile roofs. Less significant than these secondary buildings are supplementary b...