![]()

Part One

Theory

![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

Trade theory has long been at the heart of economics. Adam Smith, the father of modern economics, identified the division of labour as the key to The Wealth of Nations. This is true at any level; an individual can have much higher material living standards by specialising than by being self-sufficient. If one person produces cloth and another produces the necessary pins and needles and a third sews the garment, more clothing can be made than if each person tries to do all the tasks. In the opening chapter of his book, Smith goes a step further, describing a pin factory in which different specialists make the various components and join them together. Such manufacturing was at the heart of the industrial revolution going on around him in Scotland in 1776.

Such specialisation only works if each producer can find people to exchange his or her services, and this requires an institutional framework. Securing property rights so that when a good is exchanged, the recipient is confident of owning it, and enforceable contracts so that artisans could specialise in manufacturing with some confidence that they would receive food in return were early examples of basic institutions required for specialisation and exchange. The more the transactions and transport costs are reduced, the more willing each person will be to specialise within a larger and larger market area. For Adam Smith, the main constraint on economic growth was the extent of the market.

International trade has the same basis. A country can enjoy a greater total of goods and services through specialisation and trade than if it tries to be self-sufficient. This truth is illustrated by the falling behind, throughout history, of countries that tried to shut themselves off from trade and by the absence of such countries today — even North Korea trades.

What do countries trade? To some extent they trade for things that they cannot produce themselves, e.g. Italy sells olive oil and imports furs. This sort of trade is, however, a small and declining portion of world trade; in the early 21st century, agricultural goods and minerals accounted for less than a fifth of world trade. In practice, short of oil, some minerals and a very limited number of agricultural products, there are few goods that cannot be produced, at a cost, in most countries. Most of the world’s merchandise trade is in manufactured goods and the fastest growing sector is trade in services, both things that can be produced in almost any geographical setting.

The great contribution of David Ricardo, in the first half of Chapter 7 ‘On Foreign Trade’ in The Principles of Political Economy and Taxation (1817), was to establish comparative advantage as the basis for mutually beneficial exchange. The gains from trade do not depend upon one country being absolutely better at producing one good and a second country being absolutely better at producing another good, but on comparative differences. It is not true that when one country is more efficient than another in all activities, there are no gains from trade. Thus, Thailand may be more efficient than Laos in producing both clocks and cabbages, but if it is relatively more efficient at producing one good then there are potential gains from trade.

Comparative advantage is most simply illustrated with a numerical example and a single input. Suppose in Thailand a worker can make five clocks or produce 100 cabbages in a month, while in Laos a worker can produce two clocks or 50 cabbages. Thai workers have an absolute advantage in both activities, but have a comparative advantage in making clocks. Suppose now that a Thai farmer stops growing cabbages and makes clocks instead, and that two Laotian clockmakers start growing cabbages. As a result of this specialisation, joint production is increased: cabbage output is unchanged (100 less in Thailand, 100 more in Laos), but clock production is higher (five more in Thailand, four less in Laos).

The key to the increase in total output is the existence of differences in opportunity costs. Although Thai workers are more efficient in both activities, the opportunity cost of producing cabbages (i.e. the amount of clocks foregone) is higher than in Laos. This is a very powerful argument for trade because for any pair of countries it is inconceivable that opportunity costs will be identical for every pair of goods and services, and thus that a country does not have a comparative advantage in some activity.

Specialisation by comparative advantage creates a potential win–win situation. Several popular misconceptions about trade are simply incorrect as generalisations. It is not true that the more productive country must lose because it will be undercut, nor is it true that the less productive country will lose from trade because it cannot compete. Finally, it is logically impossible for a country to have a comparative advantage in all goods. The location of comparative advantage may not be obvious to policymakers, but if in bilateral trade one country has a comparative advantage in a good, then the other country must, definitionally, have a comparative advantage in some other good, because opportunity cost is a relative concept.

The potential gain from specialisation by comparative advantage is as true at the individual level as at the national level. Suppose two people agree to run a brain surgery and one is a better surgeon and a better manager than the other. There are still gains from specialisation; if she is relatively better at brain surgery, then she should specialise in surgery and the other person should specialise in managing the business. Of course, people can change their comparative advantage by training and education, and in the international trade context we will come to that dynamic story later. In the short-run, it may still be better to specialise by current comparative advantage while devoting resources to increasing productivity; that is why we see future brain surgeons working as waiters as they pass through their early university years in medicine.

This is not to say that comparative advantage always leads to trade. High transaction costs make trade impractical. One way to view economic development over the centuries, emphasised by Nobel laureate Douglass North, is that falling transaction costs have led to ever increasing specialisation, trade and wealth. Prehistoric trade was largely (but not entirely) barter, but having to find somebody wanting to exchange something you want for what they have to offer at a mutually convenient time is restricting. Arms-length trade in monetised economies requires institutions to ensure at a minimum that exporters receive payment and importers have recourse if a good they have paid for is not delivered. From the basic letter of credit to sophisticated instruments for hedging against exchange rate risk, such “institutions” have emerged and are constantly being refined. Innovations such as the container revolution or reduced telecommunications costs underlie the rapid growth of trade in the last half century, but causality runs both ways and such innovations were in part responses to the potential but unrealised gains from trade.

Governments may also place obstacles to international trade perhaps because they dislike some of the outcomes from specialisation by comparative advantage. In past decades, some governments resisted a situation which led to them specialising in primary products but with booming energy and mineral prices in the early 21st century countries like Canada or Norway or Australia were happy to see their commodity exports boom.

More difficult to assess are situations where trade exposes societies to drastic change. After the arrival of Columbus in 1492, the opportunities for exchange between Europe and the Americas were massive. Half a millennium later, both sides of the Atlantic have been transformed. Transatlantic trade has been an important source of higher living standards on both sides of the ocean, but the distribution of the gains from trade has been highly unequal and included huge costs. Today’s native people of the Americas may be better off than their ancestors were before European contact, but for the many who died from disease, guns or alcohol trade was of dubious benefit. The population of Mexico fell 90% in the century after 1519, and it took over 350 years for the population to regain its 1519 size; similar human devastation occurred throughout the Americas.1 Millions of Africans who were transported to slavery in the Americas suffered from high mortality rates en route and awful work conditions when they reached their destination. The British occupation of Australia in the late 1700s also involved unwilling settlers (convicts) and a high death toll among the native people; the population of Tasmania was callously and completely eliminated.

![]()

Chapter 2

The Ricardian Model

The benefits from specialisation according to comparative advantage can be powerfully illustrated by a numerical example as with the cabbage growers and clock makers in Chapter 1. A more general approach to illustrating the potential gains from trade is to represent all the production possibilities in both countries. For a pair of goods, we can do this in a two-dimensional diagram showing the production possibility frontiers.

The simplest application to trade, often called the classical trade model or Ricardian model, assumes two goods, two countries and one input. The primary input, e.g. labour, is fixed in each country, but is mobile between the two activities. The productivity of labour is constant in each activity, but labour productivities differ between countries. These are simplifying assumptions which yield a parsimonious model whose results concerning the gains from trade are powerful and general.

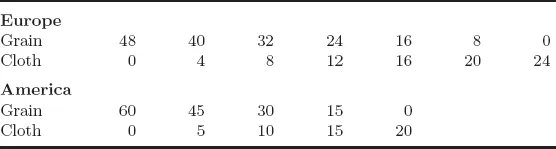

The data for the production possibility frontiers in two Ricardian economies are provided in Table 2.1. America has four workers each of whom can produce 15 kilos of grain or 5 metres of cloth, while Europe has six workers each of whom can produce 8 kilos of grain or 4 metres of cloth. This can be represented diagrammatically by the production possibility frontiers in Figure 2.1. If labour is perfectly mobile between the two activities and is divisible (i.e. a worker can work part-time in both activities without altering productivity per hour), then the frontiers are linear. Without trade, consumption of the two goods in each country cannot be at a point beyond the frontier.

Table 2.1. Alternative output combinations in two Ricardian economies.

Figure 2.1 indicates that America has an absolute advantage in the production of both cloth and grain, but America’s comparative advantage is in grain. The American production possibility frontier is flatter because the opportunity cost, in terms of foregone cloth, of producing grain is less in America than in Europe. The slope of the PPF is equal to the opportunity cost of producing an additional unit of the good measured on the vertical axis. In this case, the slope is constant and equal to one third (1/3) in America and one half (1/2) in Europe. The difference in slope of the PPFs determines the specialisation patterns that can yield gains from trade.

The gains from trade implicit in Figure 2.1 can be made explicit by constructing a box out of the two PPFs. This is done in Figure 2.2 by aligning the output levels that result from specialisation according to comparative advantage, in this case with America producing only grain and Europe producing only cloth. The rectangular box enclosed by the two axes contains all of the possible consumption points in the two countries given a joint output of 60 kilos of grain and 24 metres of cloth and a...