![]()

Chapter One

“The Old Normal” and China’s Central Bank

SECTION ONE: CHINA’S ECONOMIC FEATURES IN “THE OLD NORMAL”

In 2014, the financial market followed China’s “New Normal” closely while the “Old Normal” attracted little attention. For one thing, many considered themselves “veterans” who had lived and therefore understood the “Old Normal,” and no further study was needed. For another, the “Old Normal” was “in the past tense” with little value for research. However, I hold that the research on the “Old Normal” is significant. Only by figuring out the economic pattern and the Central Bank’s operational logics will we be able to understand the Chinese economy and the Central Bank in the “New Normal.” Or rather, only by learning the defects of the “Old Normal” will we be able to identify the reform direction in the “New Normal.”

For example, the Old Normal was plagued by “soft intervention” which was a great barrier to the liberalization of China’s interest rate. The government will undoubtedly take measures to remove this obstacle in the New Normal. In early 2014 way before the market followed New Normal, I argued that “the hardening of soft intervention,” most probably through centralized management of local governments’ debts and government performance evaluation, was a major issue in interest liberalization (in his article “De Facto Default Cannot Save China’s Debt Market” published on March 7th). In the second half of 2014, the central and subnational governments rolled out relevant policies, the milestone of which was “Opinions of the State Council on Strengthening the Administration of Local Government Debt.” This document, released in October 2014, offered a comprehensive solution to local governments’ debt problems. Hence, my prediction became a reality.

Here is another example. Balance of payments, one of the Central Bank’s four monetary policy “targets,” is closely related to the unilateral appreciation of renminbi (RMB) in the Old Normal. We can therefore predict the Central Bank’s choices against the Impossible Trinity in the Old Normal and further predict the policy shift of the Bank in the New Normal.

As far as I am concerned, the features of the “Old Normal” includes, first, economic growth driven by infrastructure construction and real estate investment; second, high synchronization of five cycles and strong trends; third, GDP-dominated macro control, other goals centering around GDP growth; fourth, unilateral rising of real estate prices; fifth, unilateral appreciation of RMB.

The following paragraphs will discuss: first, growth pattern and real estate prices; second, macro control and the synchronization of the five cycles. The features of the Old Normal mentioned above will also be covered.

Growth Pattern and Real Estate Prices

Michael E. Porter in The Competitive Advantage of Nations classifies the development of nations’ competitiveness into four stages: factor-driven stage, investment-driven stage, innovation-driven stage and wealth-driven stage. The investment-driven stage and the innovation-driven stage are wide apart. In contrast, the spacing between the factor-driven stage and the investment-driven stage and that between the innovation-driven stage and the wealth-driven stage are relatively small; most countries could go through the transition naturally. In light of this, the author holds that economic growth patterns can be simply put into two categories: one is investment-driven pattern, the other is innovation-driven pattern. Shifting from the investment-driven pattern to the innovation-driven pattern marks a country’s success in overcoming the middle-income trap and becoming a developed economy.

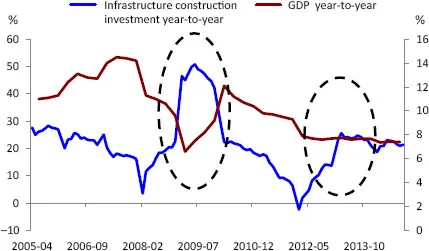

In the Old Normal, China’s economy was largely driven by infrastructure construction and real estate investment featured by government-dominated growth. It should be noted that “largely” does not imply that infrastructure construction and real estate investment accounted for over 50% of China’s GDP; it only means that their share of China’s GDP was higher than that in developed countries and that the two of them combined could literally shape China’s economic cycle. For example, in the wake of the financial crisis in 2008, the government initiated the “Four Trillion” stimulus package, the bulk of which went into infrastructure investment. Soon, the real estate sector began to recover, breathing life into the heavy industry. Another example was the end of 2012 when the economy began to pick up. Likewise, infrastructure construction and real estate investment were the first to recover, and drove other sectors.

Now we will discuss the features of infrastructure construction investment and the real estate industry.

Infrastructure construction investment drove the economy in the following ways. First, investment itself could directly generate GDP; second, infrastructure construction investment produced huge demand for manufactured goods and the expanding reproduction of the manufacturing sector produced GDP; third, such investment created favorable environment and conditions for economic development which accommodated the development of all sectors, a phenomenon known as the multiplier effect; fourth, infrastructure construction investment was government-dominated and counter-cyclical whereas other sectors such as the consumption were market-driven and pro-cyclical. This follows that when the economy went down, infrastructure construction investment became an important hedge against economy slowdown and a major force to turn the economy around.

The primary defect of infrastructure construction investment was that since the government was the absolute leader of investment, the scale and efficiency of investment were not determined by the market; the strong political influence gave rise to pronounced repercussions and uncertainties.

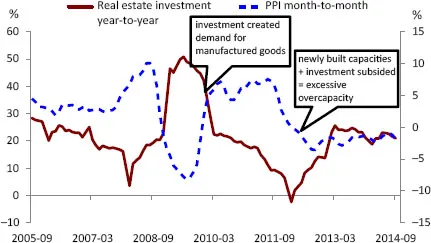

Infrastructure construction investment has significant repercussions. The repercussion of governmental stimulus was the leading driving force of China’s economic cycle. For instance, if all of a sudden the government released a large stimulus package, the demand for manufactured goods would skyrocket. Relatively liberalized markets such as concrete and steel would see expanding capacities in no time. However, when the investment wave subsided, the newly built capacities were just up and running. Declining demand for manufactured goods coupled with oversupply led to excessive overcapacity. Moreover, the corporate exit mechanism was underdeveloped in China. SOEs’ domination of capacities is largely unmarketized, because of the need to avoid large unemployment and provide a weiwen environment (stability maintenance); businesses are hard to go bankrupt, which aggravated the problem. As a result, China’s PPI has remained negative since 2011.

The uncertainty of infrastructure construction investment is three-fold.

First, the appropriateness of scale was uncertain. The government had trouble deciding the scale of a stimulus plan. If too small, the stimulus would not turn the economy around; if too large, the economy might suffer short-term overheating and long-term stagnation.

Second, the appropriateness of investment areas was uncertain. The investment project intended to boost growth might be put in the wrong place. Investment aimed at sustaining growth was usually an emergency treatment without thorough planning. All this haste might result in low efficiency or failure.

Third, the effectiveness of local governments’ implementation was uncertain. Local governments’ actions were not under the full control of the central government. One scenario was when “the policy is confined to the State Council,” or the central government exerted limited influence on local governments. Another scenario was that local governments only pretended to follow central policies by forging information and actually did otherwise. Given the multiple uncertainties around infrastructure investment, the effects of the government’s massive infrastructure investment were highly uncertain and the aftermath of the “Four Trillion” and thus the economic slowdown after 2012 took the government by surprise.

I believe that it is reasonable and necessary for a developing country to boost economy through investment in infrastructure construction, especially when the economy glides down. However, the intensity, direction and method of investment should be taken into thorough consideration. In terms of intensity, overstimulation should be avoided; in terms of direction, investment industries and areas should be chosen with discretion; in terms of method, effective supervision mechanism should be put in place to make sure the money is well spent. Infrastructure investment used to play a critical role in China, but it will eventually fade out or survive in a new form, such as the “Chinese version of Marshall Plan,” a catchphrase at the end of 2014.

Real estate was the second most important driving force in the Old Normal Chinese economy. It bore similarities as well as differences with infrastructure investment. Real estate investment created huge demand for manufactured goods as did infrastructure investment, making it a downstream industry of heavy industry. It differs from infrastructure investment in that: first, real estate was not completely government-led, or rather, the government preferred indirect measures such as land supply and policy adjustment over direct investment and price intervention; second, having no multiplier effect, real estate investment was more of a financial asset; third, real estate cycle, smoother and longer, was closely related to prices and trading volume. The fact that current month chain price index and trading volume were primary indicators of real estate investment testified that this industry was much more liberalized.

In retrospect, despite cyclical fluctuations in prices, the duration and range of increase were more significant than those of decrease. Therefore, the price change could be considered as unilateral increase. The rise began in 1998 when housing system reform kicked in and accelerated in 2004 with the introduction of the bid invitation, auction and listing system with only two brief drops in 2008 and 2012. According to statistics from State Statistics Bureau, the national average price was 2,050 yuan per square meter in 1999, 2,700 in 2004 and 5,800 in 2012; it rose by 110% from 2004 to 2012, with an annual growth rate of 10%. In Beijing, the average price was 5,600 yuan per square meter in 1999, 5,050 in 2004 and 17,000 in 2012; it rose by over 240% from 2004 to 2012, with an annual average growth rate of over 16%. For reference, the CPI base was 432 in 1999, 456 in 2004 and 580 in 2012; it rose by only 27% from 2004 to 2012, with an average increase rate of a mere 3%.

The rise of CPI was far slower than that of real estate prices

A lot has been said about the rising house prices, mainly about the supply and demand.

On the supply side, commercial residential houses were mainly supplied by real estate companies while affordable houses and self-built houses took only a small share. Since the certification of real estate companies was under strict regulation, the market was in some way a monopoly market. When the cost rose, real estate companies would undoubtedly pass on the burden to consumers, pushing up the house prices. The cost of real estate companies includes land cost, labor cost and building material cost, the third being related to the capacity and cycle of manufactured goods. I will now elaborate on the land cost and labor cost. First, considering land cost, the Land Administration Law provides that the nation in line with the law could requisition or expropriate land and offer compensation while any organization or individual must apply to the government for construction land, which makes the government the sole supplier of land and the monopoly of land rights. In result, the pricing of land was to a great degree up to the government. As land-selling revenue was a major part of local governments’ fiscal revenue, those governments were more than willing to see the price rise. Second, labor cost began to surge around 2006 as China passed the Lewis Turning Point where labor supply came into shortage. Real estate companies passed on the rising labor cost to consumers, pushing up house prices.

Demand can be discussed in two categories: investment demand and consumption demand. First, investment demand derived from expectations for rising house prices based on experiences and the faith that local governments would rescue the market given their excess dependence on land revenue. The rising house prices propped up expectations for further increase, creating a positive feedback loop that stimulated demand for investment. The loose monetary policy from 2009 to 2010 contributed to corporate and individual wealth. Real estate, whose value is easy to preserve and increase, became the optimal investment choice. Prior to 2013, investment demand in real estate mainly came from four groups: Wenzhou professional speculators, coal mine owners from Shanxi, the second generation of the rich or the politicians and international hot money. Second, consumption demand was linked to housing system reform, urbanization, demographics, increasing income, traditions, underdeveloped affordable housing system and hukou, to name just a few. After the housing system reform, the long depressed consumption demand exploded, a precondition for the rising price. Urbanization began to speed up after 1996, with urbanization rate rising from 29% to 54% from 1995 to 2013; the shift in the demographic profile also gave rise to house demand. The period between 1980 and 1987 marked the peak of new births. Given that inelastic demand comes from the 25-to-30-year-olds, 2004 stood to be the year of accelerating price rise. Since 2004, urban per capita disposable income has maintained a year-on-year growth rate of over 10%. The rise of income was the prerequisite for the release of inelastic demand. In Chinese tradition, renting an apartment is only temporary while buying a house is a must for marriage. Hence the saying “mothers-in-law are the culprits of high house price.” China is yet to develop a functional affordable housing system. In consequence, some inelastic demand that should have been covered by the government was handled through the market, leaving the real estate market over-liberalized. Some cities grant hukou only to those with houses, pushing up inelastic demand.

In a nutshe...