![]()

Chapter 1

Building a Liveable City:

The Singapore Experience

K H O O T e n g C h y e*

Introduction

With over 5.5 million inhabitants living on 720 square kilometres of land, Singapore today is one of only a few cities in the world recognised for achieving high standards of liveability and sustainable development, despite a high population density. This would have been difficult to imagine in the 1960s when Singapore was plagued by economic woes, poor infrastructure and squalid conditions and populated by about 1.7 million people, a third of the present population. This leap, from a developing nation to a thriving global metropolis ranked among the world’s most liveable cities in the space of 40 years, was the result of decades of deliberate planning and implementation that sought to strike a balance between density, development and liveability.

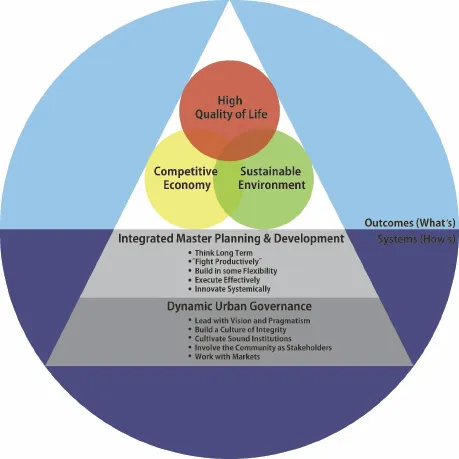

In 2008, the Centre for Liveable Cities (CLC) was established to capture the explicit and tacit knowledge underlying Singapore’s unique urban development experience, and to distil some of the general principles that have guided Singapore’s urban planners and policy makers over the years. Its research has covered over 130 original interviews with past and present cabinet ministers and senior officials, several of whom are quoted in this chapter. Through its research, CLC found that Singapore has held three key outcomes constant in its pursuit of liveable urban development:

(i)A competitive economy in order to attract investments and provide jobs;

(ii)A sustainable environment because the city has to survive with limited natural resources, especially in terms of land and water; and

(iii)A high quality of life, including the social and psychological well-being of the population.

In addition to these three outcomes, two elements have been vital to successful urbanisation in Singapore. First, it was crucial to have a system of integrated planning and development that kept the outcomes of a liveable city constantly in view, over the long term.

Second, subscribing to an urban governance approach that was dynamic helped sustain the conditions needed for a thriving liveable city.

Together, these elements form the components of the CLC Liveability Framework (Figure 1).1

The liveable city outcomes

In 1992, the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) posited that the social, environmental and economic needs of a country must be met but in balance with one another. There are however no absolute levels whereby liveability is met. Instead, the challenge is to optimise the trade-offs at each stage of growth. Hence, each city must take into account its own needs, resources and context when planning its development.

Figure 1. CLC Liveability Framework

Source: Centre for Liveable Cities.

The philosophy behind the liveable city outcomes identified in the CLC Framework has nevertheless remained consistent for more than four decades of Singapore’s development.

Outcome 1: A competitive economy

Singapore’s competitive economy has contributed greatly to the city-state’s liveability quotient. At the most basic level, residents need opportunities to make a living and achieve a degree of economic security. This is as true today as it was in the early days of development when industrialisation helped squatters and rural residents transit to a modern urban economy.

Singapore’s urban systems have had an integral role in supporting the country’s economic development — a priority in its earliest years — from the purposeful allocation of land and facilities to the supply of utilities and a strong transport infrastructure with local and global connections, giving the economy a competitive edge over its regional neighbours.2 In turn, a competitive economy has allowed the city-state to generate income to sustain itself, develop and create yet more opportunities for growth in a virtuous cycle.

With further development, a well-functioning economy and a liveable environment have become ever more important, since cities worldwide now compete for investment and mobile talent:

If the people are rooted to the place, that’s how you can help ensure that there’s a certain robustness to it and even for those who are foreigners … the liveability and vibrancy are important … To the extent that we can root them through clustering of knowledge and people and like-minded activities, we will do that.3

Beh Swan Gin, former managing director, Economic Development Board

Outcome 2: A sustainable environment

Singapore was committed to sustainable development early on in order to preserve and make the most of what few natural resources it had. Provisions for clean air, clean water and green cover were integral to city planning from the start. Careful thought was even given to wind patterns for the location of industrial estates to the west of Singapore to prevent the spread of air pollution to the city. When Japanese company Sumitomo wanted to build a petrochemical plant in the mid-1970s, pollution control requirements threatened to raise costs and deter the project:

But the Ministry of Environment said, “No, we should not concede. It will pollute Singapore.” This went to Cabinet and Cabinet agreed with the Ministry of Environment. They said, “No, we insist.” Then Sumitomo proceeded and put in the investments necessary.4

S Dhanabalan, former Cabinet minister

Environmental considerations have not been assumed to be at odds with economic development. Instead, they have been integrated into urban planning and embedded into a larger social and economic narrative by framing them as a means to distinguish Singapore from its regional peers. In the early years, a clean and green city was a way to show foreign investors that Singapore was a well-run country and thus a good and pleasant place to set up business.

Outcome 3: A high quality of life

The notion of a high quality of life encompasses many aspects of urban living, including economic, social, environmental and psychological. A key part of Singapore’s attraction today is its pleasant and well-planned environment — a far cry from the early days of slums, squalor and crime. Indeed, apart from the provision of amenities, creating a sense of personal security was an important aspect of developing Singapore’s new towns:

Create a sense of safety … It is no use having good surroundings, if you are afraid all the time … We have Neighbourhood Police Posts — police who know the people in that neighbourhood, so they know when strangers come in.5

Lee Kuan Yew, former prime minister

Retaining a sense of engagement in the physical landscape has since become a way to encourage Singaporeans to feel connected to the land. Since the mid-1980s, city planning in Singapore has also tried to give more emphasis to the character and soul of the city-state, one that encompasses culture, identity and aesthetics.

Balancing the three liveability outcomes

These three liveable city outcomes are linked directly to Singapore’s outcome indicators at the national level. They are published in the Ministry of Finance’s Revenue and Expenditure Estimates for each financial year, ensuring that all government agencies know the big picture of the overall state of urban development. It also signals to the public that the government is committed to and serious about making Singapore liveable.

Developing a liveable Singapore involves balancing the three interdependent (and often overlapping) outcomes. Focusing too much on one at the expense of the others could easily lead to undesirable outcomes. Nor are the outcomes always so discrete: solutions to achieve one outcome could create opportunities towards another.

For instance, Singapore’s quest for water self-sufficiency has given rise to a niche sector of specialised companies that provide water reclamation and desalination services. With further investment by the government, this nascent water sector is now expected to provide 11,000 jobs and add S$1.7 billion to the economy by 2015.

Taken together, these three outcomes form Singapore’s planning and development regime.

Integrated master planning: implicit principles

Singapore’s integrated master planning system has enabled the government to create and manage urban systems that balance the different guiding priorities on both short- and long-term scales in response to changes in a dynamic political, economic and social environment. A key differentiating factor for Singapore’s planning regime is that its plans do not just stay on paper — they are implemented and executed through dedicated organisations, with expertise and resources. Five implicit principles underpin Singapore’s integrated master planning approach.

Principle 1: Think long term

At the heart of the integrated master planning approach is Singapore’s overarching Concept Plan, covering the country’s land use over a time horizon of up to 50 years. The plan, created through an inter-agency effort, ensures that all key land use requirements for the city are met and that individual urban systems, such as transport, water or public housing, do not work in isolation.

Taking a long-term view has been important in two other ways. First, it has helped officials keep the three liveability outcomes in balance, at both the planning and implementing stages. Second, taking a long-term view has helped the government identify problems in the future, making it expedient to take steps to pre-empt the problem or to develop a good project ahead of its time. In the early decades of Singapore’s rapid growth, even longer planning time frames were needed:

[We made] a decision to project to ‘Year X’ which was 100 years. Why? Because I said to myself that if we don’t do that, we will certainly run out of land. [We may] build to too low a density when you project for the short term. And then we run out of space.6

Liu Thai Ker, former CEO, Housing and Development Board ...