- 444 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Science and Society

About this book

-->

The latest advances and discoveries in science have made, and continue to make, a huge impact on our lives. This book is a history of the social impact of science and technology from the beginnings of civilization up to the presen

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

THE BEGINNINGS OF CIVILIZATION

Early ancestors of man

Almost three million years ago, manlike creatures lived on the shores of Lake Rudolf in Kenya. The skull of one of these early “homenoids” was found in 1972 by Richard E. Leakey. Pouring fine sand into the reconstructed skull, Dr. Leakey and his associates measured the brain capacity as 800 c.c. - considerably less than the modern brain volume of 1400 c.c., but still remarkably large considering the early date of the skull. Potassium-argon dating of the volcanic ashes in which the skull was found established its age as approximately 2.8 million years.

At the Oldavai Gorge in Tanzania, not far from Lake Rudolf, Louis and Mary Leakey (Richard Leakey’s father and mother) discovered many remains of a somewhat more advanced homenoid which they called Homo habilis. Among these remains, which were shown to be 1.8 million years old, Louis and Mary Leakey found many chipped stones, probably representing tools and weapons used by Homo habilis. The discoveries of the Leakey family, as well as those of Raymond Dart and Robert Broom, indicate that the early evolution of the human race probably took place in Africa. The early ancestors of man seem to have been hunter-gatherers living in small bands on the East African grasslands.

Terra Amata

We catch another glimpse of early man at the Terra Amata site at Nice in Southern France, where 300,000 years ago, in a warm period between the Mindel and Riss glacial eras, a small tribe came every summer to spend a few weeks hunting and food-gathering on the shore of the Mediterranian. The huts which these early people built on their brief summer visits to the beach are among the earliest man-made dwellings ever discovered. They were between 26 and 29 feet long, and were built in an oval shape out of leafy saplings leaned against a central ridge pole. The central ridge pole in each hut was supported by vertical tree trunks embedded in the sand. Around the oval perimeter of the huts were walls of large stones for protection against the wind, and inside the huts were hearths on which small fires were built. (This is almost the earliest use of fire known, although earlier hearths have been found in strata of the Mindel ice age at Verteszölos in Hungary.)

Water for the camp came from a nearby spring. The level of the Mediterranian Sea was then 85 feet higher than it is today. It covered most of the plane of Nice, and near the camp it had cut a small cove with a sandy pebble-strewn beach into the western slope of Mount Boron. On the slopes of the mountain grew heather, sea pine, Aleppo pine and holm oak. A human footprint nine and one-half inches long is preserved in the sand of the ancient dune. Evidence shows that these summer visitors of 300,000 years ago spent their time gathering shellfish, hunting and making tools. Among the animals which they hunted were stag, an extinct elephant, wild boar, ibex, rhinoceros and wild ox. They stayed at Terra Amata only a few weeks each year, and then continued their travels, following the migrations of the animals which they hunted.

The Soultrian and Magdalenian cultures

In the caves of Spain and Southern France, not far from the Terra Amata site, are the remains of vigorous hunting cultures which flourished at a much later period, between 30,000 and 10,000 years ago. The people of these upper paleolithic cultures lived on the abundant cold-weather game which roamed the southern edge of the ice sheets during the Wurm glacial period: huge herds of reindeer, horses and wild cattle, as well as mammoths and wooly rhinos. The paintings found in the Dordogne region of France, for example, combine decorative and representational elements in a manner which contemporary artists might envy. Sometimes among the paintings are stylized symbols which can be thought of as the first steps towards writing.

In this period, not only painting, but also tool-making and weapon-making were highly-developed arts. For example, the Soultrian culture, which flourished in Spain and southern France about 20,000 years ago, produced beautifully worked stone lance points in the shape of laurel leaves and willow leaves. The appeal of these exquisitely pressure-flaked blades must have been aesthetic as well as functional. The people of the Soultrian culture had fine bone needles with eyes, bone and ivory pendants, beads and bracelets, and long bone pins with notches for arranging the hair. They also had red, yellow and black pigments for painting their bodies.

Fig. 1.1 Cave painting from the cave of Altamira. Public domain, Wikimedia Commons

The Soultrian culture lasted for 4,000 years. It ended in about 17,000 B.C. when it was succeeded by the Magdalenian culture. Whether the Soultrian people were conquered by another migrating group of hunters, or whether they themselves developed the Magdalenian culture we do not know.

The agricultural revolution

Beginning about 9,000 B.C., the way of life of the hunters was swept aside by a great cultural revolution: the invention of agriculture. Starting in western Asia, the neolithic agricultural revolution swept westward into Europe, and eastward into the regions which are now Iran and India.

By neolithic times, farming and stock breeding were well established in the Near East. Radio-carbon dating shows that by 8,500 B.C., people living in the caves of Shanidar in the foothills of the Zagros mountains in Iran had domesticated sheep. By 7,000 B.C., the village farming community at Jarmo in Iraq had domesticated goats, together with barley and two different kinds of wheat.

At Jerico, in the Dead Sea valley, excavations have revealed a prepottery neolithic settlement surrounded by an impressive stone wall, six feet wide and twelve feet high. Radio-carbon dating shows that the defenses of the town were built about 7,000 B.C.. Probably they represent the attempts of a settled agricultural people to defend themselves from the plundering raids of less advanced nomadic tribes.

By 4,300 B.C., the agricultural revolution had spread southwest to the Nile valley, where excavations along the shore of Lake Fayum have revealed the remains of grain bins and silos. The Nile carried farming and stock-breeding techniques slowly southward, and wherever they arrived, they swept away the hunting and food-gathering cultures. By 3,200 B.C. the agricultural revolution had reached the Hyrax Hill site in Kenya. At this point the southward movement of agriculture was stopped by the great swamps at the headwaters of the Nile. Meanwhile, the Mediterranian Sea and the Danube carried the revolution westward into Europe. Between 4,500 and 2,000 B.C. it spread across Europe as far as the British Isles and Scandanavia.

Mesopotamia; the invention of writing

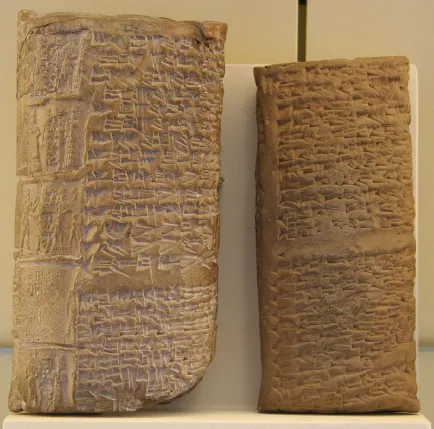

In Mesopotamia (which in Greek means “between the rivers”), the settled agricultural people of the Tigris and Euphraties valleys evolved a form of writing. Among the earliest Mesopotamian writings are a set of clay tablets found at Tepe Yahya in southern Iran, the site of an ancient Elamite trading community halfway between Mesopotamia and India.

The Elamite trade supplied the Sumarian civilization of Mesopotamia with silver, copper, tin, lead, precious gems, horses, timber, obsidian, alabaster and soapstone. The practical Sumerians and Elamites probably invented writing as a means of keeping accounts.

Fig. 1.2 Cuneiform tablet of the old Babylonain period (c. 1800 B.C.) with its container printed with cylinder seals. Uploaded by Einsamer Schütz, [CC BY-SA 3.0], Wikimedia Commons

The tablets found at Tepe Yahya are inscribed in proto-Elamite, and radio-carbon dating of organic remains associated with the tablets shows them to be from about 3,600 B.C.. The inscriptions on these tablets were made by pressing the blunt and sharp ends of a stylus into soft clay. Similar tablets have been found at the Sumarian city of Susa at the head of the Tigris River.

In about 3,100 B.C. the cuneiform script was developed, and later Mesopotamian tablets are written in cuneiform, which is a phonetic script where the symbols stand for syllables.

Mesopotamian science

In the imagination of the Mesopotamians (the Sumerians, Elamites, Babylonians and Assyrians), the earth was a flat disc, surrounded by a rim of mountains and floating on an ocean of sweet water. Resting on these mountains was the hemispherical vault of the sky, across which moved the stars, the planets, the sun and the moon. Under the earth was another hemisphere containing the spirits of the dead. The Mesopotamians visualized the whole spherical world-universe as being immersed like a bubble in a limitless ocean of salt water.

By contrast with their somewhat primitive cosmology, both the mathematics and astronomy of the Mesopotamians were startlingly advanced. Their number system was positional, like ours, and was based on six and sixty. We can still see traces of it in our present method of measuring angles in degrees and minutes, and also in our method of measuring time in hours, minutes and seconds.

The Mesopotamians were acquainted with square roots and cube roots, and they could solve quadratic equations. They also were aware of exponential and logarithmic relationships. They seemed to value mathematics for its own sake, for the sake of enjoyment and recreation, as much as for its practical applications. On the whole, their algebra was more advanced than their geometry. They knew some of the properties of triangles and circles, but did not prove them in a systematic way.

Although the astronomy of the Mesopotamians was motivated largely by their astrological superstitions, it was nevertheless amazingly precise. For example, in the beginning of the fourth century B.C., incredibly accurate tables of new moons, full moons and eclipses were drawn up by Nabu-rimani; and about 375 B.C. Kidinnu, the greatest of the Babylonian astronomers, gave the exact duration of the solar year with an accuracy of only 4 minutes and 32.65 seconds. (This figure was found by observing the accumulated error in the calendar over a long period of time.) The error made by Kidinnu in his estimation of the motion of the sun from the node was smaller than the error made by the modern astronomer Oppolzer in 1887.

In medicine, the Mesopotamians believed that disease was a punishment inflicted by the gods on men, both for their crimes and for their errors and omissions in the performance of religious duties. They believed that the cure for disease involved magical and religious treatment, and the diseased person was thought to be morally tainted. However, in spite of this background of superstition, Mesopotamian medicine also contained some practical remedies. For example, the prescription for urinary retention was as follows: “Crush poppy seeds in beer and make the patient drink it. Grind some myrrh, mix it with oil and blow it into his urethra with a tube of bronze. Give the patient anemone crushed in alppanu-beer.”

Until recently it was believed that the Mesopotamians had no idea of hygiene and preventive medicine. However, the following remarkable text was published recently. It is a letter, written by Zimri-Lim, King of Mari, who lived about 1780 B.C., to his wife Shibtu: “I have heard that Lady Nanname has been taken ill. She has many contacts with the people of the palace. She meets many ladies in her house. Now then, give severe orders that no one should drink in the cup where she drinks. No on should sit on the seat where she sits. No one should sleep in the bed where she sleeps. She should no longer meet many ladies in her house. This disease is contagious.”

We can guess that the Mesopotamians were aware of some of the laws of physics, since they were able to lift huge stones and to construct long aquaducts. Also to their civilization must be credited a great cultural advance: the invention of the wheel. This great invention, which eluded the civilizations of the western hemisphere, was made in Mesopotamia in about 3600 B.C..

The early Hebrew culture was closely related to that of the Mesopotamian region, and a vivid picture of the period which we have been describing can be obtained by reading the Old Testament.

It may seem surprising that so many of the early steps in the cultural evolution of mankind were taken in a region much of which is now an almost uninhabitable desert. However, we should remember that in those days the climate of the Near East was very different - very much wetter and cooler than it is now. Even today, the process of drying up after the last ice age is not yet complete, and every year the Sahara extends further southward.

Early metallurgy in Asia Minor

Whatever the ancient civilizations of the Near East knew about chemistry and metallurgy, they probably learned as “spin-off” from their pottery industry. In the paleolithic and neolithic phases of their culture, like people everywhere in the world, they found lumps of native gold, native copper and meteoric iron, which they hammered into necklaces, bracelets, rings, implements and weapons. In the course of time, however, after settled communities had been established in the Near East for several thousand years, it became much more rare to find a nugget of gold or metallic copper.

Although the exact date and place are uncertain, it is likely that the first true metallurgy, the production of metallic copper from copper oxide and copper carbonate ores, began about 3,500 B.C. in a region of eastern Anatolia rich in deposits of these ores. It is very probable that the discovery was made because colored stones were sometimes used to decorate pottery. When stones consisting of copper oxide or copper carbonate are heated to the very high temperatures of a stone-ware pottery kiln in a reducing atmosphere, metallic copper is produced.

Imagine a potter who has made this discovery - who has found that he can produce a very rare and valuable metal from an abundant colored stone: He will abandon pottery and go into full-scale production as a metallurgist. He will try all sorts of other colored stones to see what he can make from them. He will also try to keep his met...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- 1. The Beginnings of Civilization

- 2. Ancient Greece

- 3. The Hellenistic Era

- 4. Civilizations of the East

- 5. Science in the Renaissance

- 6. Galileo

- 7. The Age of Reason

- 8. The Industrial Revolution

- 9. Evolution

- 10. Victory Over Disease

- 11. Atoms in Chemistry

- 12. Electricity and Magnetism

- 13. Atomic and Nuclear Physics

- 14. Relativity

- 15. Nuclear Fission

- 16. Hiroshima and Nagasaki

- 17. Genesplicing

- 18. Artificial Intelligence

- 19. Caring for the Earth

- 20. Looking Towards the Future

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Science and Society by John Scales Avery in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Science History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.