![]()

Chapter 1

The Post-Crisis Regulatory Landscape: An Overview

1. Free Marketeers and the Dislike of Regulation

Free marketeers hate regulation in any shape or form — and this is not surprising at all. What is surprising, however, is that this stance has not changed despite the destruction inflicted on humanity by the global financial crisis as people lost their homes, jobs and retirement funds in the name of the free market. In the aftermath of the crisis free marketeers who oppose regulation and advocate deregulation came in three categories. Category one are those who claim that the crisis was caused by excessive regulation. Category two comprises those who suggest that deregulation was not a cause of the crisis. The most outrageous claim, however, is made by category three free marketeers who suggest that no major deregulation has taken place in the last 30 years or so. One can only wonder if category three free marketeers are talking about Planet Earth, but more likely they are in a state of denial.

One of the free marketeers belonging to category one is Senator John Ensign, chairman of the National Republican Senatorial Committee, who went on Face the Nation to put forward his diagnosis of the economic meltdown. He said: “Unfortunately, it was allowed to be portrayed that this was a result of deregulation, when in fact it was a result of overregulation” (Huffington, 2008). Another example is Ambler (2011) who contends that “the 2008 financial crash was not caused by a lack of regulation” and that “an excess of regulation was a larger factor, creating as it did the illusion of security”. However, the facts on the ground tell a different story — one example would suffice at this stage (but we will come across many more examples as we move on). Had over-the-counter (OTC) derivatives been regulated as suggested by Brooksley Born in the 1990s, we would have gone a long way in at least reducing the effects of the global financial crisis. As early as 1997, the then Fed Chairman, Alan Greenspan, fought to keep the derivatives market unregulated. On the advice of the President’s Working Group on Financial Markets, the Congress and President allowed the so-called “self-regulation” of the OTC derivatives market when they enacted the Commodity Futures Modernization Act of 2000 (Summers et al., 1999).1

As for category two, we have the dissenting voices of members of the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission (FCIC, 2011). In their dissenting statement, Commissioner Keith Hennessey, Commissioner Douglas Holz-Eakin and Vice Chairman Bill Thomas rejected what they call the “too simplistic the hypothesis that too little regulation caused the crisis”. They argued against the proposition that “the crisis was avoidable if only the US had adopted across-the-board more restrictive regulations, in conjunction with more aggressive regulators and supervisors”. Instead they adopt what they call a “global perspective”, arguing that a credit bubble appeared in both the US and Europe and that large financial firms failed in Iceland, Spain, Germany and the UK, where stricter regulation was in operation. Hence they rule out as causes of the crisis the political influence of the financial sector in Washington, the “runaway mortgage securitization train”, the corporate and regulatory structures of investment banks and Alan Greenspan’s deregulatory ideology. The fact of the matter is that Iceland, Spain and the UK were hurt badly by the crisis because they followed the American model and allowed their financial oligarchies to run the show. Germany as a whole was not affected as badly by the crisis because the Germans proved to be wise enough not to follow the American model and abandon manufacturing industry, neither did they adopt the British motto of “who needs manufacturing industry when we have the City?” Germany is mentioned here perhaps because some German banks and pension funds collapsed as they took the bait and accumulated US-manufactured junk assets.

Under category three we have two members of the FCIC with dissenting voices: Peter Wallison and Arthur Burns who dismiss as causes of the global financial crisis deregulation or lax regulation. They argue that “explanations that rely on lack of regulation or deregulation as a cause of the financial crisis are also deficient”. Against the facts on the ground they suggest that no significant deregulation of financial institutions occurred in the last 30 years. Specifically they contend that the repeal of the Glass–Steagall Act (which is the prime example of deregulation) had no role in the crisis.

2. The Facts on the Ground

Common sense and an ideological free consideration of the facts on the ground would tell us that deregulation was a major cause of the crisis and that wholesale deregulation has taken place since the early 1980s. The contribution of regulatory failure and deregulation to the eruption of the global financial crisis is emphasized by the FCIC (2011). In its report on the crisis, the Commission declared:

There was an explosion in risky subprime lending and securitization, an unsustainable rise in housing prices, widespread reports of egregious and predatory lending practices, dramatic increases in household mortgage debt, and exponential growth in financial firms’ trading activities, unregulated derivatives, and short-term “repo” lending markets, among many other red flags. Yet there was pervasive permissiveness; little meaningful action was taken to quell the threats in a timely manner.

The report refers in particular to the “pivotal failure” of the Fed to stem the flow of toxic mortgages, which it could have done by setting prudent mortgage lending standards. Reference to the contribution of deregulation is made at the outset as follows:

More than 30 years of deregulation and reliance on self-regulation by financial institutions, championed by former Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan and others, supported by successive administrations and Congresses, and actively pushed by the powerful financial industry at every turn, had stripped away key safeguards, which could have helped avoid catastrophe.

The Commission also refers to failure to use existing regulation:

Yet we do not accept the view that regulators lacked the power to protect the financial system. They had ample power in many arenas and they chose not to use it. To give just three examples: the Securities and Exchange Commission could have required more capital and halted risky practices at the big investment banks. It did not. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York and other regulators could have clamped down on Citigroup’s excesses in the run-up to the crisis. They did not. Policy makers and regulators could have stopped the runaway mortgage securitization train. They did not.

The Commission argues that the financial industry itself played a key role in weakening regulatory constraints on institutions, markets and products. The FCIC’s report makes it explicit that regulators have been captured by big financial institutions, arguing that it was not surprising that “an industry of such wealth and power would exert pressure on policy makers and regulators”, pointing out that “from 1999 to 2008, the financial sector spent $2.7 billion in reported federal lobbying expenses, while individuals and political action committees in the sector made more than $1 billion in campaign contributions”.

Spaventa (2009) points out that regulators were caught by the crisis with their eyes wide shut, having resisted attempts to allow regulation to keep pace with financial innovation. He presents his view as follows:

This was coherent with the prevailing creed: that markets were self-regulating and only required the lightest possible public touch; that self-interest would lead to proper risk assessment; that capital deepening was always good for growth, no matter how.

Deregulation becomes the law of the land when regulators argue against regulation. In a 2003 speech, Fed Vice Chairman Roger Ferguson praised “the truly impressive improvement in methods of risk measurement and the growing adoption of these technologies by mostly large banks and other financial intermediaries”. His boss, Alan Greenspan, is quoted as saying that “the real question is not whether a market should be regulated” but “the real question is whether government intervention strengthens or weakens private regulation”. Richard Spillenkothen, the Fed’s director of Banking Supervision and Regulation from 1991 to 2006, is quoted as saying that “supervisors understood that forceful and proactive supervision, especially early intervention before management weaknesses were reflected in poor financial performance, might be viewed as (i) overly-intrusive, burdensome and heavy-handed, (ii) an undesirable constraint on credit availability, or (iii) inconsistent with the Fed’s public posture” (FCIC, 2011).

Regulation by an external agent is needed because “private regulation” and “self-regulation” do not work in an industry where business is motivated primarily by greed. In Oliver Stone’s 1987 movie Wall Street, Gordon Gekko spells it out on the role of greed in the finance industry by saying the following:

Greed, for lack of a better word, is good. Greed is right. Greed works. Greed clarifies, cuts through, and captures, the essence of the evolutionary spirit. Greed, in all of its forms; greed for life, for money, for love, knowledge, has marked the upward surge of mankind and greed, you mark my words, will not only save Teldar Paper, but that other malfunctioning corporation called the USA.

It is true that Gordon Gekko is a fictitious character, but what he said is a true representation of what motivates the financial oligarchy. While greed cannot be regulated, it leads to something that can and should be regulated: fraud and corruption. In this book an argument will be made repeatedly, that corruption and fraud provide the best justification for regulation.

3. Boom and Bust

The regulatory landscape should be shaped by what is needed to avoid another crisis aided by the lessons learned from the last crisis. Dozens of studies have been conducted to determine the causes of the global financial crisis, in which case there is no need to repeat the exercise here. However, it is useful to recount what happened and how the boom (or bubble) in asset markets was followed by a big bust. Emphasis is placed on two observations: (i) the boom and bust cycle starts with deregulation and regulatory failure and (ii) every boom involves elements of corruption, fraud and greed.

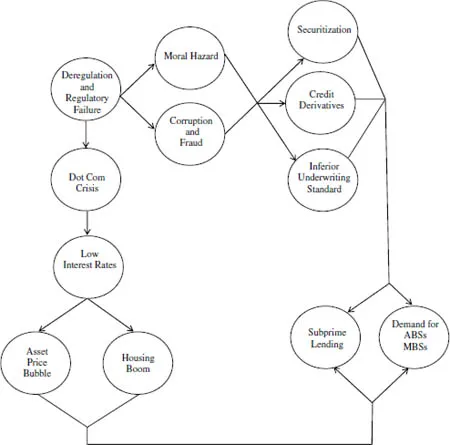

Figure 1.1 is a schematic representation of the boom. The starting point is deregulation and regulatory failure. For 50 years following the implementation of the Glass–Steagal Act in 1933, financial stability prevailed, but that came to an end with the advent of the savings and loan crisis of the 1980s, which was a direct result of the wholesale deregulation initiated by a champion free marketeer, Ronald Reagan. The wave of deregulation continued into the 1990s, culminating with the abolition of the Glass–Steagal Act, which gave bankers a free hand to do as they pleased and led to the creation of jumbo financial institutions that were allowed to gamble with depositors’ money. We did not have to wait long after that to witness the bursting of the dot-com bubble, causing the recession of the early 2000s. In response to the recession, the Fed reacted by reducing interest rates to stimulate the economy, a policy that was in place for too many years. Under an environment of low interest rates, people rushed to buy houses on a massive scale, using adjustable-rate mortgages as they were led (by mortgage brokers) to believe that it was a great deal. A housing market boom was initiated and so was a general asset price bubble, particularly in the stock market.

Figure 1.1: The Boom

Deregulation and regulatory failure enhanced moral hazard and provided the right environment for rampant greed-driven corruption and fraud. By securitizing every cash flow under the sun, bankers invented the Frankenstein financial assets of asset-backed securities (ABSs), mortgage-backed securities (MBSs), collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) and their variants such as CDO squared. Another “great” invention was an insurance policy called credit default swaps (CDSs) intended to hedge the risk of default faced by the holders of the Frankenstein securities. Together with predatory lending and inferior underwriting standards, these securities and derivatives were used as a conduit for fraud, particularly because no one understood how they worked and not even their inventors could estimate the degree of risk embodied in them (this is not to say that the inventors and their bosses did not realize that they were junk securities). The ABSs, MBSs and CDOs were given the AAA designation by the credit rating agencies (CRAs) which encouraged demand for these toxic assets by the world investment community.2 This wave of “financial innovation” led to rapid growth in subprime lending, which was enhanced on the demand side by the housing boom and general asset price bubble. While the party lasted everyone was happy. Mortgage lenders were happy to lend and keep subprime loans off their books via securitization. Issuers of ABSs were happy to get their commissions. Borrowers were happy to get loans without scrutiny. Investors were happy to acquire assets that were “risk-free” and offered a return of hundreds of basis points over that offered by US Treasuries. Members of the financial oligarchy (bankers and financiers) were happy to receive billions of dollars worth of bonuses without any contribution to human welfare. The situation was simply an orgy of hubris and excesses.

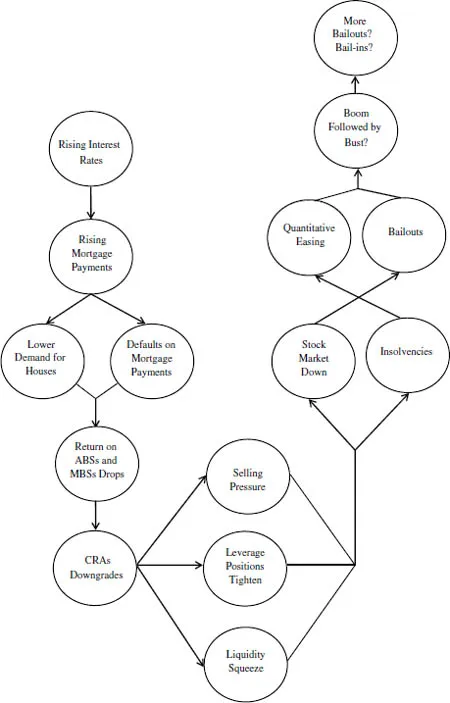

Like every party, this party came to an end, a very unhappy end. Figure 1.2 represents how the bust materialized — that is, how the party came to a very unhappy end. Just like the boom started with low interest rates, the bust started when the Fed embarked on a tight policy whereby the official interest rate was raised 17 times during the period 2004–2006. As a result, payments on adjustable rate mortgages started to rise, leading to a slowdown in the demand for houses and massive defaults on mortgage payments. The defaults experienced far exceeded what was predicted by the risk models used by financial institutions, including those based on the Gaussian Copula (see, for example, Reid, 2015). As a result, ABSs, MBSs and CDOs lost their appeal as the return on these assets dwindled. Being the backward-looking institutions they are, the CRAs downgraded these assets, leading to a tightening of leveraged positions as hedge funds and banks had to meet margin calls. To raise capital, banks and hedge funds started to sell off liquid assets. A liquidity squeeze ensued as the interbank market dried up and financial institutions became reluctant to lend to each other. Insolvencies arose and stock markets took a nose-dive. The crisis was in full swing as Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy and American International Group (AIG) found itself unable to meet demand for payoffs on CDSs.3

The policy response was shaped by the desire to save big financial institutions, those that are too politically connected to fail and those that owed money to those that are too politically connected to fail (such as AIG owing billions of dollars to Goldman Sachs). A bailout program was approved to save AIG and major banks. The response to the Great Recession took the shape of quantitative easing, a policy whereby the central bank prints new money to finance the purchase of government securities and toxic assets from financial institutions. Both bailouts and quantitative easing amount to sowing the seeds of the next crisis. Bailouts enhance moral hazard and excessive risk-taking. Quantitative easing not only enhances moral hazard but it is also a very bad policy from a macroeconomic perspective. It has inflationary implications, it punishes savers (with bad consequences for economic growth) and it creates asset price bubbles, with adverse distributional consequences. We should not forget that the low interest rates maintained over a long period of time played a big role in the initiation of the crisis, so it is fair to conclude that the current environment of low interest rates maintained through quantitative easing may lead to the next crisis. If and when another crisis causes the failure of financial institutions, the government will respond with more bailouts. The fear now is that governments may resort to bail-ins, refinancing banks by confiscating (more appropriately, stealing) depositors’ money.4

Figure 1.2: The Bust

4. Key Players and Culprits

Although the global financial crisis was American in orig...