![]()

Part I

Reference Points

![]()

Chapter 1

Reference-Based Decisions in Finance

Fernando Zapatero*

Abstract

We survey a number of financial settings linked by the importance of a reference point in the decision making process. For each of them, we discuss how the reference points affect the decisions. We conclude that it is not a coincidence that reference points are essential to many financial settings. Reference points boost the incentives of the individuals, which we argue is the reason why they are so prevalent. Stronger incentives lead to more effort, which leads to higher achievement and the desire for more reference point-based decisions.

Keywords: Reference point, utility function, incentives, reputation concerns

JEL Classification: D03, D81, G02

1.Introduction

Prospect Theory, developed by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky in a series of papers (mainly Kahneman and Tversky 1979, and Kahneman and Tversky 1992) is one of the most influential theories in Economics, and is the result of many experiments conducted by them and a large number of collaborators. A key component of Prospect Theory is a reference point that, among other things, splits in two different parts, with different properties each, the decision’s space of the economic agents. In particular, when wealth is above the reference point, the economic agent is risk-averse; when wealth is below the reference point, the economic agent is risk-loving. However, this is not the only reference point that affects agents’ decisions mentioned in the literature. Rabin (1998) offers a few more examples, mainly related to the utility function of the individuals. Utility functions are representations of the preferences of the individuals, and as such, individuals are “born” with them, as if they were assigned by “nature.” However, in practice, there are reference points that are given by other economic agents — and not just by nature. For example, the benchmarks that are established to evaluate the performance of some economic agents: many funds managers are compensated depending on their performance with respect to a given reference point, typically an index of securities; the compensation of some CEOs depends on their performance with respect to some reference point, like an index or the price of the stock of the company they manage on a given date.

It is possible that there is no other connection among these reference points than the fact that they affect economic agents’ decisions, but there is no underlying common reason that justifies why, in so many instances in economics decisions, a reference point is a critical factor in the determination of the optimal choice. However, our conjecture is that there is an ultimate explanation why it is efficient for decision making — at least in economics — to use a reference point, whether it is given by nature, possibly as a human trait that improves the fitness of the individual (as described by Rayo and Becker, 2007) or established by another principal because since we humans are used to reference points, it is an efficient way to motivate economic agents.

Throughout the paper, we analyze some of the main reference points studied in the financial literature. We will conclude with some considerations about the importance of reference points in economic decisions. This is a classification of the reference-dependent decisions we will explore in this survey:

•Maximizing individual utility:

—Habit formation.

—Relative wealth concerns.

•Incentives from benchmarking performance.

—Money managers.

•Relative performance evaluation.

—Managerial compensation.

—Financial analysts.

•Reputation effects.

—Star CEOs.

—Financial analysts.

Over the next sections, we will discuss the reference points that affect each decision maker. In the case of CEOs, we will briefly overview two different reference points, one determining their performance evaluation, the other reputation or career concerns. We do not intend this classification to be exhaustive or even fully accurate. We propose it as a convenient starting point for the analysis.

2.Habit Formation

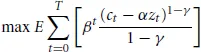

Consider standard utility objectives:

where c(t) represents consumption at time t. In this model, the utility the individual experiences at a given point in time only depends on consumption realized at that time. This is called the independence property of expected utility theory. However, a number of scholars have questioned its validity over the years. The particular deviation from the independence property we consider here was first modeled by Pollak (1970), and Ryder and Heal (1973).

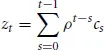

In particular, an individual has habit formation — or internal habit formation, as opposed to external habit formation, in a terminology we will explain later — when utility of the individual at time t depends on consumption at time t compared to previous consumption. By “previous consumption”, we mean the history of consumption of the individual up to time t. For tractability, models use some type of average of past consumption. For example, a popular way to model habit formation considers that the objective of the individual is the following:

where z is often called the standard of living, an average of previous consumption,

α is a measure of the importance of past consumption and ρ < 1 is a measure of the memory about past consumption, so that the smaller ρ, the more relevant is recent consumption in calculating the average.

The average of past consumption –z in the previous model — is the reference point: the value of the contribution of current consumption to utility depends on z. The intuition is straightforward. Take for example two individuals with the same utility function, and both consume an identical amount (say we can measure it as 50) this period (t). Standard utility theory would assign the same value to their utility for the current period t. According to standard utility theory, their previous consumption is irrelevant in the determination of their utility at t. Suppose, though, that one of the individuals is used to a high level of utility in the past (say an average of 100) so that this period is consuming substantially below that level because of a business failure. On the other hand, the other individual was used to a level of consumption lower than the current (say 20), but has received a big promotion that makes the higher consumption possible. Habit formation accounts for the change and assigns a higher level of utility to the second individual.

The notion of habit formation has solid foundations in psychology. In particular, habit formation and the way we model habit formation in finance is closely related to some facts established by psychologists about adaptation. There is plenty of evidence from the research in psychology that the human being is very adaptive: Frederick and Loewenstein (1999) analyze the concept of hedonic adaptation or “adaptation to stimuli that are affectively relevant” (definition of the authors). Hedonic adaptation happens in both “favorable and unfavorable” circumstances. Hedonic adaptation is pervasive — if not uniform, across people, as Frederick and Loewenstein (1999) discuss. For example, when people experience a positive event in their lives, like a large monetary award as result of winning a lottery, in general, they experience an immediate increase in happiness, but it is short-lived, and after a while, they go back to a level of happiness comparable to before the favorable event.1 The symmetric case is similar: after some unfavorable event, people experience an immediate drop in happiness, maybe associated with depression, for example, but the majority of individuals bounce back after a period of time and recover a level of satisfaction comparable to the one they were enjoying before the event. We also note that adaptation is an efficient way to process information. As Frederick and Lowenstein (1999) state, it “enhances perception by heightening the signal value of changes from the baseline level”. The connection to the notion of habit formation we introduced before is straightforward. The formula for z in the habit formation utility described above is a variation of what psychologists call adaptation level in terminology introduced by Helson (1947). The difference between the current level of stimulus — consumption in our model of habit formation — and the adaptation level is called hedonic state, and would correspond to the argument of our utility function.

Habit formation became popular in finance as a possible way to explain some empirical regularities that appeared to be at odds with the predictions of standard utility models. In particular, Mehra and Prescott (1985), in a thought-provoking and very influential paper, showed that the equity premium (or difference in return between stocks and bonds) observed from many decades until their study, could not be explained with standard utility unless the degree of risk-aversion of the individuals were unreasonably high.2 This observation — for which there is not a consensus explanation yet — was called the equity premium puzzle, and a large amount of work has been devoted to try to explain it from the moment Mehra and Prescott (1985) was published. One of the avenues explored in the literature has been habit formation. In particular, Constantinides (1990) studied the possible effects of habit formation on the equity premium and showed that it could help explain the puzzle. On the other hand, Detemple and Zapatero (1992) showed in an equilibrium setting that habit formation could make easier, but also harder, to explain the equity premium puzzle, depending on the specific interaction between consumption and the standard of living z defined before.

Another empirical puzzle around the same time that Mehra and Prescott came up with the equity premium puzzle was the excess smoothness of consumption. This refers to the fact that consumption is smooth compared to income. It is a puzzle since income finances consumption, however, for some reason, economic agents’ consumption does not fully react to changes (upwards or downwards) in income. This had been known for decades, and addressed through the theory of permanent income — individuals use a reference income, the permanent income, to make purchase decision. However, Deaton (1987) showed that this theory did not match the data, and left the question of what explains smoothness of consumption open. Sundaresan (1989) argued that habit forming individual utilities could be an explanation. Certainly, it is a property of habit formation that the individual will not fully react to an increase in income because of the effect it will have on the future standard of living z, given that if it grows too much, it will make harder to keep utility high.

Campbell and Cochrane (1999), in a very influential paper as well, introduce a version of habit formation in an attempt to explain the equity premium puzzle, along with other properties of security prices that the literature had unveiled over that decade: given the large number of attempts to solve the equity premium puzzle, researchers started to look for other properties that the many models proposed should have in order to be credible. For example, historically, interest rates have been low and relatively not volatile. Campbell and Cochrane (1999) consider a representative agent model with habit formation and stochastic risk aversion. The stochastic risk aversion would be the result of aggregating over a population of individuals with different degrees of risk aversion, as shown by Chan and Kogan (2002). Campbell and Cochrane (1999) show the properties that the resulting stochastic discount factor should have to explain all the empirical properties required by the literature. However, Xiouros and Zapatero (2010) show that the parameter values the Campbell and Cochrane (1999) model requires for their representative agent are not supported by the data on individual choices.

In summary, habit formation has received a fair amount of attention in the literature; however, it has failed to be embraced as a first order property of preferences that needs to be including in existing models. At this point, it seems clear that habit formation alone cannot explain a full set of properties of security prices. However, there are many decisions (economic and otherwise) we observe frequently among individuals that are difficult to reconcile with standard utility theory, but fully consistent with habit formation. We have sketched the connection between the economic theory of habit formation and the psychological studies on adaptability. As we argued before, Frederick and Lowenstein (1999) contend that adaptability increases the value of a signal with respect to the reference baseline. The equivalent to that statement in an economic interpretation of habit formation is that habit formation increases the marginal utility of consumption: when the agent gets used to a new level of consumption, the motivation to increase consumption above that level (the marginal utility) increases. Marginal utility is the driver that moves agents to invest money or effort on achieving an extra unit of consumption. How can we explain that many successful entrepreneurs, writers, academics (to mention some examples) keep working as hard as if they were just starting their careers? Fast adaptation (or habit formation) that quickly gets them used to the current level of success and motivates them to work to achieve the next level — as with habit forming utilities — would explain a behavior that seems at odds with standard utility theory.

3.Relative Wealth Concerns

This expression encompasses a number of utility representations and individuals’ decision patterns characterized by the the motivation to compete in an economic sense with a reference person or group of persons. In particular, we include here the preferences popularly known as “keeping up with the Joneses”. The idea behind this type of preferences is that individuals derive utility from their consumption or wealth compared to the consumption or wealth of the reference group. The latter is a reference point that will affect the economic decisions of the individuals who display this type of preferences. This reference group cou...