![]()

1Early concrete history

Somewhat mixed opinions can be found about what can be regarded as the first concrete. Various authors have various views about the correct definition of concrete. The composition or mixture design and the production methods of the first concrete were different from what we have today. However, the material has proved its strength and durability over thousands of years.

The earliest binders, or the glue, were often a combination of burnt lime and hydraulic lime. Lime is burned from a reasonably pure limestone, from which the CO2 is driven out and calcined at 1000–1100°C but does not harden under water. Burnt lime treated with water and mixed with sand gives a lime mortar. The hardened mortar will continuously absorb CO2 from the air and harden, something that in many ways is the reverse process of burning.

Hydraulic lime, on the other hand, hardens under water like the cements we have today. These are produced from impure limestone containing silicium acids and aluminum and iron oxides and need higher temperatures in the burning process.

It is the product or powder from these sources that is called cement today.

What do the dictionaries say about CONCRETE?

•A simple “English Dictionary” [1] states that Concrete is composed of particles united in one mass.

•A small “Dictionary of Science” [2], states that “Concrete is a building material made of stone, sand, cement and water.”

•A more advanced American science and technical encyclopedia [3] states that Concrete is a “versatile engineering material consisting of a Hydraulic cementing substance (usually Portland cement), aggregate, water, and often controlled amounts of entrained air. Concrete is initially a plastic, workable mixture which can be molded into a variety of shapes. Strength is developed in the hydration reaction between the cement and water. The products, mainly calcium silicates, calcium aluminates, and calcium hydroxide, are relatively insoluble and bind the aggregate in a hardened matrix.”

•An older Norwegian encyclopedia [4] states, as an introduction, that “Concrete is a building material of a cured mixture of sand, stone, cement and water.”

Based on the dictionaries and encyclopedias we have a relatively wide range of possibilities to judge if we are dealing with concrete. Other definitions made by modern concrete technologists can be useful, but are not necessarily precise.

One of the great teachers of cement and concrete chemistry, F.M. Lea, in his book “The Chemistry of Cement and Concrete” [5] provides detailed definitions. He defines cement as “adhesive substances capable of uniting fragments or masses of solid matter to a compact whole.” He says that concrete is “an artificial conglomerate of gravel or broken stone with sand and lime or cement.”

Gartmann [6] writes in his book about glue or lime (translated from Norwegian): “We hear about the first lime-burners early in the seventeenth century. The old name for stone that contains more than 50% calcium carbonate is ‘limestone’ or ‘glue stone,’ and this we have kept to our time. We find this name again in places where lime has been burnt in old days as for example Limhamn where Swedish cement industry started its activity.”

Sven Thaulow writes, by way of introduction, in an article about cement in September 1967: [7] (from Norwegian) “To find material that can bind or glue together stone material to an artificial stone has always been a goal for human beings. The Assyrians and the Babylonians used clay and bitumen, the Phoenicians and the Egyptians used gypsum and lime, and the Greeks knew the art to burn lime. The Romans discovered some natural cements – pozzolans with so-called hydraulic properties, i.e. materials that could harden under water, contradictory to lime that needs air to achieve strength.”

The well-known Canadian concrete chemist Pierre-Claude Aïtcin has in the introduction to his book “Binders for Durable and Sustainable Concrete” [8] differentiated the glues of ancient times into three categories;

•Gysum (anhydite) based

•Lime based

•Pozzolan based

Even if some of the ancient concretes that are found seem to be combinations of these categories, and some also might contain some natural cements, Aïtcin’s systematization seems reasonable. The gypsum-based glue is based on a simple burning process, and Aïtcin claims with reference to Stark and Wicht that the binding properties of gypsum were discovered some 10 to 20 000 years ago. Most of the concretes that were found before the Roman time and are mentioned in the following chapters are lime based. Aïtcin, referring to several authors, claims that lime-based concretes were also found 10 000 to 20 000 years ago.

With reference to Felder-Cassagrande (1997), he mentions mortar found in Nevali Core in Turkey 22 600 years ago. Lime glue has been used by several cultures around the world, but some of them have only been reported on a small scale. Aïtcin for example refers to Deloye, who mentions lime mortar in walls in Bali in Indonesia in 200 BC and to Thornton, who refers to a limebased floor from 3000 BC in Dadiwan in the Ganow province in China.

The pozzolan-based binders are also in a way lime based, but they are hydraulic, can harden under water, and are more durable. Even if we find some examples of pozzolan-based glue earlier, it is only well into the Roman times that these really got a foothold.

An interesting point in the development of concrete is that it seems that we find long periods when there was very little development in the technology. This might partly be due to the fact that the knowledge about this fantastic material and its use was limited to religious activities. The priestesses in various religions kept the knowledge a secret and used it to strengthen their position. We can also see examples of this in the later millenniums when the development in the concrete environment between the fall of the Roman Empire and until the beginning of the 1700s was nearly limited to churches and monasteries.

How did the use of concrete start?

It is surmised that concrete originated in early times when humans found glue at the edge of the hollow in the ground where they had their cooking fires. When it rained, on the fire edge they found a glue-like substance that could be used to form a stable material. The quality of the glue depended on the material in which the fire hollow was made and the intensity of the fire. This observation had probably taken place in many locations, but the ability to systemize the observation and analyze the material that was found varied and was the foundation of the knowledge that came into existence later. The final product might have been gypsum, lime, lime mixed with a silicium-based pollution or a pozzolan material.

It has been said that the first cultured human being was the one who went out into the field, picked flowers, and put them together in a bouquet. The first concrete technician was he or she who observed that the edge of the fire hollow could glue together sand and gravel, who protected the glue powder from rain, and who understood that the glue formed irrespective of the kind of soil the fires were made in.

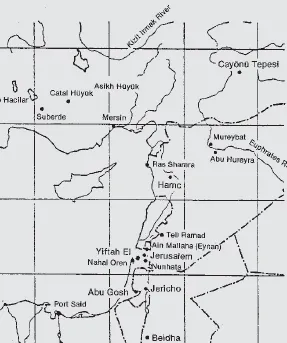

1.1Galilee

In a floor built 9000 years ago in Yiftah El, west of Jerusalem, remnants of concrete have been found. The 180m2 floor must have used about 8m3 of concrete with about two tons of lime as a binder [9]. The considerable volume of lime must have come from a rather large oven and an organized burning procedure. Fragments of fire-proof material from something that might have been like an oven have also been found in the industrial area of Yiftah El. The concrete that was found shows remarkably high strength, density, and durability properties. Researchers claim that burning of lime was the first use of fire for production purposes.

Jericho in Gallileia is the oldest Neolithic town in history. After the fall of Jericho, according to the Bible in the year 1200 BC, researchers have found several layers of concrete from earlier settlements, among them a polished concrete floor, under the rubble.

The floor from where the researchers later took out samples for testing was discovered while working with a bulldozer during work on a new motorway. In 1886 and 1887, the Israeli archeologist Garfinkel and retired Professor Malinowski from Gothenburg in Sweden, who specialized in concrete, took out samples of the concrete that were analyzed in the laboratory [9,11]. The date of the origin of the samples was found to be about 7000 BC.

Map showing the Neolithic discoveries of polished concrete floors. [9]

(Neolithic period, when products of polished artificial stone were found – the last of the two Stone Age periods) [10]

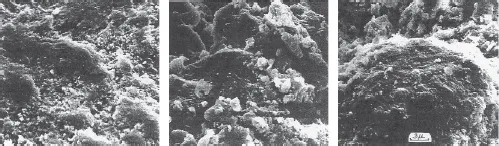

Malinowski [11] states that the lower part of the floor consists of lime concrete with a thickness of 6–8 cm. The concrete is beige brown and has a very fine polished surface and in some places is covered with a reddish brown topping. The aggregate consists of crushed rock with sizes up to 10 mm, with very finely distributed mortar around it. The concrete is cast in two layers. The upper layer is a very hard mortar of 3–4 mm in thickness, with good bonding to the bottom layer.

SEM-pictures of the fracture planes of the samples[11]

The laboratory testing, among others, showed:

• High density of 2.2 to 2.4 g/cm3

• Remarkably high compressive strength of 40 MPa

• Chemical analysis showed 90% of calcite, with small quantities of quartz, etc.

Workers in the Potala temple in Lhasa produce a very durable floor by hand hammering coarse aggregate into a dry and hard mortar of sand, clay and lime.

Picture of the finished floor, probably several hundred years old, in the Dalai Lama’s summer palace. These floors are water repellent and nearly crack free, in contrast to “modern” concrete on floors and walkways in the neighborhood, which have a considerable amount of cracking. A contributing reason might be the very low humidity and air pressure (3600–3700 m above sea level), much lower than in cases normally considered.

Malinowski’s description of the floors in Galilee reminds me of the visual appearance, method, and use of a much later date. In August 2007, I had the pleasure of visiting Lhasa in Tibet, China. Here are some pictures from the visit.

1.2Mesopotamia and Ch...