![]()

Chapter 1

The Linguistic Prescience of George Boole

We begin with a brief discussion of the insightful and prescient vision of the relation between language and mind that George Boole (1815–1864) presents in his 1854 magnum opus:

AN INVESTIGATION

of

THE LAWS OF THOUGHT

ON WHICH ARE FOUNDED

THE MATHEMATICAL THEORIES OF LOGIC AND PROBABILITIES

The present work draws on boolean structure extensively, though Boole’s Laws, as I will call the above cited work, is not a normal historical citation in formal semantics or generative grammar. In the former domain we expect to see foundational work such as Frege (1893), Tarski (1931), and Montague (1970). In the latter, Chomsky (1986, Ch 1) notes sources ranging from Plato and Aristotle through Descartes, the Port Royal grammarians, von Humboldt, John Stuart Mill, and more recently the linguist Otto Jesperson (1924).

The name George Boole is notably missing from these source lists, and not without reason. Boole was primarily a mathematician. His Laws presents the first instantiation of what we know today as Boolean Algebra, a well developed subfield in mathematics with extensive application in logic and information sciences. Boole was not an incipient linguist. There is no danger of confusing his Laws with the Port Royal Grammar (Arnauld and Lancelot 1975; see Chomsky 1966/2009). But Boole shares with contemporary, and earlier, linguistic theory the view that there is a tight relation between language and mind. The opening sentence in the Laws begins:

The design of the following treatise is to investigate the fundamental laws of those operations of the mind by which reasoning is performed; to give expression to them in the symbolical language of a Calculus, . . . (p. 1).

Boole feels “That Language is an instrument of human reason, . . . ” (p. 26); “The elements of which all language consists are signs. . . ” (p. 27) and “. . . in investigating the laws of signs, . . . , the immediate subject of examination is Language, with the rules which govern its use;” (p. 27). And Boole continues here with evidence for the tight interconnection between language and mind:

Nor could we easily conceive, that the unnumbered tongues and dialects of the earth should have preserved through a long succession of ages so much that is common and universal, were we not assured of the existence of some deep foundation of their agreement in the laws of the mind itself (p. 27).

Is this not the modern linguists’ Universal Grammar (UG)! Compare Chomsky (1975, p. 4) who agrees that “language is a mirror of the mind” understood as: More intriguing, to me at least, is the possibility that by studying language we may discover abstract principles that govern its structure and use, principles that are universal by biological necessity and not mere historical accident, that derive from mental characteristics of the species. So the grammars of different languages (Japanese, Malagasy, English, . . . ) are all special cases of UG, which is biologically determined.

Given Boole’s investigation of language and mind, it is perhaps not surprising that he makes other observations compatible with current linguistic thinking. Here are a few examples, with just a quick comment regarding their relevance in modern syntax and semantics:

“Definition — A sign is an arbitrary mark, having a fixed interpretation, and susceptible of combination with other signs in subjection to fixed laws dependent upon their mutual interpretation” (p. 28). Does this not anticipate Frege’s compositional semantic interpretation?

“The Romans expressed by . . . “civitas” what we designate by . . . “state.” But both they and we might equally well have employed any other word” (p. 28). The arbitrariness of the sign is, again, usually attributed to de Saussure (1916).

Boole distinguishes between primary and secondary propositions — the latter being ones that relate propositions to each other. For example (p. 58) “The sun shines” is primary. . . ”, “If the sun shines the earth is warmed” is secondary. He then points out that some sentences built with what today we call binary boolean connectives (and, or, if-then) are primary, not being “resolvable into” secondary ones. An example (p. 59) of linguistic interest is: “Men are, if wise, then temperate cannot be resolved into If all men are wise then all men are temperate”.

Now, after the explosion of linguistic work created by Chomsky’s Syntactic Structures in 1957, many linguists were concerned to formulate operations that syntactically derived one expression from another (or both from a given abstract source). It seemed at first that many pairs of sentences derived from the same source had the same logical meaning: Ted smokes and drinks was derived from Ted smokes and Ted drinks, and they are indeed true in the same states of affairs (models). Another operation derived Ted wants to leave and Ted wants Ted to leave from the same source. But it wasn’t long before linguists noticed that these derivational operations failed to yield logical paraphrases with quantified phrases: Some of the men expected to be drafted is not true in the same models as Some of the men expected some of the men to be drafted (Jackendoff 1972, p. 205).

Once again Boole is ahead of the pack.

Lastly, lest we overstate Boole’s linguistic prescience, we note that generative grammar has several concerns that were simply not shared by Boole. One was the productivity of the derivational processes used to generate expressions. They were recursive, so from a finite set of words (a lexicon) we derive infinitely many expressions: He knows a doctor, He knows a doctor who knows a doctor, He knows a doctor who knows a doctor who knows a doctor, . . . In contrast Boole did illustrate recursion using and and or: Wealth consists of things transferrable, limited in supply, and either productive of pleasure or preventive of pain (p. 65) in which a disjunction is embedded within a conjunction. But iterativity per se is not discussed and we find no “unbounded” examples, such as John and either Sam or both Sue and either . . . or no remarks about deriving infinitely many expressions with finite means.

![]()

Chapter 2

Logic as Universal Grammar

In this chapter, I provide the motivation for taking standard logics — Sentential Logic, First Order Logic, Higher Order Logic — as models of linguistic analysis. Our presentation is informal, designed to be intelligible and hopefully interesting to scholars who are not familiar with the mathematical perspectives that logic brings to linguistic analysis. The later chapters presuppose some basic mathematical proficiency, manipulating functions and relations.

Originally I thought primarily of linguists as the audience for this chapter. My exposition of first order logic is hardly novel. But perhaps the linguistic perspective I take is somewhat novel. A recent book Three Views of Logic: Mathematics, Philosophy, and Computer Science 2014, by Loveland et al., presents logic from three substantive perspectives, none of which is the linguistic one taken here.

1. Sentential Logic (also called Propositional Logic; ‘Logic’ may be replaced by ‘Calculus’ in these expressions).

First and higher order logic define classes of languages, as we see shortly, but Sentential Logic is basically just a single language (with some notational variation of interest). We begin with it as it is syntactically and semantically the simplest of the logics we discuss, and it illustrates in a simple way several basic logical concepts.

In general a logic specifies three things: (1) syntactically, a set of expressions (a language), (2) semantically a definition of truth in a model in terms of which entailment is defined, and (3) a definition of proof, a syntactic characterization of the entailment relation. We consider proofs only in this chapter.

SENTENTIAL LOGIC

The Language (SL) Syntactically, SL is a set of expressions called formulas (or sentences) constructed in two steps: first, an infinite set {P1, P2, . . .} of syntactically unanalyzable basic formulas is stipulated. Second, SL itself is defined to be the minimal set of expressions containing the basic formulas and closed under appropriate combinations with and, or, and not. Specifically, the rules of the grammar of SL are:

(1)a.All basic formulas Pi are in SL (noted Pi ∈ SL).

b.If p and q are in SL (noted: p, q ∈ SL) then (p and q) ∈ SL. p and q are the conjuncts of (p and q), itself called a conjunction of sentences. For ‘(p and q)’ we often write ‘(p & q)’.

c.If p, q ∈ SL then (p or q) ∈ SL. p and q are its disjuncts and (p or q) itself called a disjunction.

d.If p ∈ SL then (not p) ∈ SL. (not p is called a negation; The parentheses are not needed).

(For the record these rules are given more formally in an Appendix to this chapter).

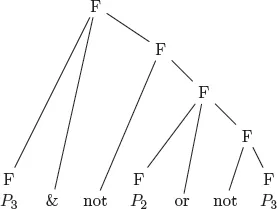

For example (P3 & not(P2 or not P3)) is a formula. The tree diagram below summarizes the argument that this is so (F = ‘Formula’).

Some common alternate notations: ∧ is often used for and, ∨ for or, and ¬ for not. We reserve these symbols for other purely semantic purposes later. Basic formulas are often called atomic but we use ‘atomic’ in a purely semantic sense later. We have used infix notation, writing the binary boolean connectives and and or between the formulas they combine with. In prefix (Polish) notation these connectives are written formula initially and often abbreviated A, O, and N. In prefix notation the formula in (3) would be:

(3)AP3NOP2NP3

In either infix or prefix notation we observe (when the definitions are given more rigorously) the following facts:

Fact 1. Each p ∈ SL is either a basic formula or derived in just one way by combining with and, or, and not.

So each formula is either a basic formula, a conjunction, a disjunction, or a negation of formulas, but never more than one of these simultaneously.

Fact 2. Each p ∈ SL contains just finitely many basic formulas and p itself is a finite sequence of symbols. (The set SL is infinite, so it is an infinite collection of finite objects.)

The Semantics of SL The semantic interpretation of SL formulas depends on just one primitive notion — trut...