![]()

Chapter Five

Modes of Religious Spirituality

Some Christian and Islamic Legacies

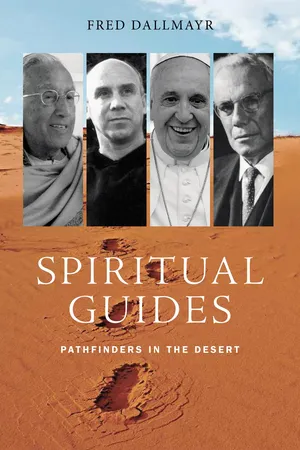

Having discussed, in the preceding chapters, four exemplary recent or contemporary spiritual leaders, the time has come for broader theoretical (philosophical/theological) reflections on the meaning of religious spirituality and its different modes. As I see it, adopting a broader theoretical perspective does not necessarily mean exiting from spiritual engagement to gain a “view from nowhere”; rather, to maintain traction, reflection has to stay close to experience (this is also why real-life mentors are memorialized at the front of this book). Thus in the following observations I aim not to abscond from but rather to move more deeply into the spirituality exemplified in prior chapters. One point that emerges from these chapters is the close connection between (what one may call) “vertical” and “lateral” spirituality, that is, between a spiritual orientation toward divine “transcendence” and one toward fellow human beings, or else between religious faith and concrete praxis. It seems that today, the invocation of God or the divine divorced from any lateral engagement is simply no longer tenable; at the same time, lateral praxis severed from spiritual moorings arouses the suspicion of self-centered manipulation. Paul Tillich spoke in this context of a “kairological moment”—an expression picked up by Panikkar and in different terms by Merton. For Panikkar, the close interpenetration of faith and lateral praxis—captured in the phrase “sacred secularity”—was even a unique temporal event or a “hapax” phenomenon.1

As the present chapter shows, the two dimensions have historically tended to be more neatly distinguished—although they were never completely divorced. To make sense of the two dimensions from a historical perspective, I introduce in the following a distinction between two types of spirituality: a “gnostic” or illuminationist type oriented toward unity with God and an agape-centered type oriented toward engagement with and service to one’s fellow beings. Expressed in linguistic terms, the first type gives preference to monologue (of the believer with God or of God with himself), while the second grants priority to dialogue or conversation. Behind these types emerges, of course, the traditional theological hierarchy of the “two worlds”: the this-worldly and the other-worldly, the “secular” and the “sacred” domains. What Panikkar calls the “hapax” phenomenon is the experience that, in our time, the two domains can no longer be neatly separated. This does not mean that they are simply amalgamated or fused; rather, the difference or distinct integrity is maintained in their correlation. The phrase sometimes used by Martin Heidegger, that “Being is beings”—where “is” has a transitive status—points precisely to this kind of differentiated correlation (the “ontic-ontological difference”), located beyond theism, atheism, and pantheism.2

Apart from delineating two main types of spirituality, the present chapter aims to lend to the topic not only greater historical depth but also (and still more importantly) greater geographical breadth—something surely desirable in our globalizing age. In this respect, our era certainly places numerous question marks behind Rudyard Kipling’s famous dictum that “West is West, East is East, and never the twain shall meet.”3 Perhaps, in Kipling’s time, the statement still had a ring of truth. When, in 1893, the great Indian Swami Vivekananda visited the Parliament of the World’s Religions in Chicago, he reportedly told a journalist inquiring about his impressions: “I bring you spirit, you give me cash.” His response reflected a prevailing sentiment at the time about a deep cultural divide according to which Western culture was synonymous with materialism, while the East resonated with spirit or spirituality. Even if it was perhaps plausible at that time, the division no longer prevails today (at least in this crude form). When, a hundred years after Vivekananda’s visit, another meeting of the Parliament of the World’s Religions was held in Chicago in 1993, the delegates—numbering nearly seven thousand—pledged themselves to work for a worldwide “transformation in individual and collective consciousness,” for “the awakening of our spiritual powers through reflection, meditation, or positive thinking”—in sum, for “a conversion of the heart.” In the words of the keynote speaker, Robert Muller (a former deputy secretary general of the United Nations), the aim was to build “a world cathedral of spirituality and religiosity.”4

As we know, of course, from hindsight, the noble goal was not achieved—maybe in part because of the relative sidelining of the “lateral” or practical side of spirituality (in favor of gnosis). In an effort to guard against this sidelining—and also against the opposite danger of a facile absorption of spirituality into consumer culture—this chapter first of all reflects on the meaning of religious “spirituality” as it has been handed down by a number of religious traditions. Seen from the vantage point of these traditions, spirituality is not (certainly not principally) a form of individual faculty or psychic subjectivism; rather, it more precisely involves a mode of self-transgression: an effort to rupture narcissism or self-centeredness by opening the self toward “otherness” (which is variously described as God, as cosmos or the world-soul, or as other human beings). For the sake of brevity, my discussion focuses chiefly on the traditions of Christianity and Islam—although I offer some side glances at other spiritual legacies. Within the confines of these traditions, I invoke the distinction between spiritual types (previously mentioned)—in full recognition of the fact that the typology inevitably shortchanges the rich profusion of spiritual life over the centuries. Following some broad theoretical reflections, my presentation exemplifies these reflections by turning to a number of prominent spiritual leaders or guides. Returning to the contemporary situation, the concluding section asks which mode or modes of spirituality may be most fruitful and commendable in our present, globalizing context.

The Traditional Meaning of Spirituality

As the word indicates, “spirituality” derives from “spirit” and hence designates (or is meant to designate) some manifestation of the work of spirit. Most of the great world religions have terms that are akin to “spirit” or capture some aspect of it. Thus we find in the Hebrew Bible the term ruach, in the Arabic of the Qur’an ruh, in the Greek version of the New Testament the word pneuma (and/or logos), translated in the Latin Vulgate as spiritus—and the list could probably be expanded to include the Sanskrit brahman and the East Asian tao. Unfortunately, this concordance or parallelism of terms does not yet offer clues for unraveling their meanings. All the words mentioned are inherently ambivalent and open to diverse readings. Thus, to take the nearest example, the English “spirit” is closely related to “spirited,” “spiritistic,” and even to “spirit” in the sense of an alcoholic beverage; in turn, the French equivalent, esprit, conjures up other connotations (of wittiness, intellectual cleverness, or virtuosity)—not to mention the profusion of meanings associated with the German Geist.5 How can we make headway in this multivocity? Here it is good to remember the core feature of religion and/or spiritual experience: the transgression from self to other, from “immanence” to (some kind of) “transcendence.” When viewed from this properly religious angle, “spirit” and “spirituality” must somehow participate in this transgressive or transformative movement; differently put, they must be seen as bridges or—better still—as vehicles or vessels suited for navigating the transgressive journey.

Descending from the level of metaphor, it should be clear that spirit and spirituality cannot simply be equated with or reduced to a human “faculty,” as the latter term has been understood in traditional anthropology and psychology. Traditional teachings about “human nature” commonly distinguish between at least three main faculties or attributes: the faculties of reason (or mind), will (or willpower), and emotion or sensation (a tripartition reflected, for example, in the Platonic division of the human psyche into nous, thymos, and appetite). While reason enables us to “know,” will—in this scheme—enables us to “act” and emotion or sensation to “feel.”6 Located squarely in human “nature,” none of these faculties can be directly identified with spirit or spirituality—although none of them should be construed as its simple negation or antithesis. Thus, without being antirational or irrational, religious spirit cannot be equated with human rationality—because it is the work or breath of the spirit that allows reason to reason and to know anything in the first place. Likewise, spirit cannot be collapsed into will for the simple reason that divine grace and transformation cannot merely be willed or unwilled (although it may require a certain human willingness or readiness). Finally, spirit cannot or should not be leveled into sentimentality or emotionalism—despite the fact that it cannot operate without engaging human sentiment or feeling in some way. It is in order to guard against such equations that religious traditions typically insist on terminological distinctions. Thus the Hebrew ruach is set over against binah (rational mind) and nephesh (organic life); the Arabic ruh over against’ aql (reason or intellect) and nafs (desire); the Greek pneuma over against nous and thymos; the Latin spiritus over against ratio and voluntas. None of these distinctions—it is important to note—should be taken in the sense that spirit is elevated into a kind of super-or hyper-faculty: far from being another, though higher, property or attribute, spirit basically supervenes and unsettles all properties by virtue of its transformative-transgressive potency.

What this means is that spirit not only resists terminological univocity; it also disturbs ontological and anthropological categories. As a transgressive agency, spirit addresses and transfuses not only this or that faculty but the entire human being, body and mind, from the ground up. In traditional language, the core of the “entire human being” tends to be located in the “heart” or the “soul” (corresponding to the Chinese hsin, meaning “heart-and-mind”)—provided these terms are not in turn substantialized or erected into stable properties. To this extent, one might say that spirit and spirituality are, first of all, affairs of the heart (or heart-and-mind).7 This means that, without being an attribute or faculty, spirit also cannot be defined as a purely external or heteronomous impulse; rather, to perform its work, it necessarily has to find a resonance or responsiveness “inside” human beings—which is the reason that spirituality, quite legitimately, is commonly associated with a certain kind of human “inwardness.” (This insight is one motivation behind Tillich’s distinction between heteronomy, autonomy, and theonomy and Panikkar’s distinction between heteronomy, autonomy, and ontonomy.) Looking at the development of religious traditions, one can probably say that religious history shows a steady deepening and also a growing complexity of inwardness.

Thus, during the early phases of Christianity, spirituality was closely linked with doctrinal theology, which, in turn, was mainly the province of a clerical or ecclesiastic elite. Church historians speak in this context of a “spiritual” or “mystical theology,” linking this term with such names as Pseudo-Dionysius and Jerome and, later, Bernard of Clairvaux and St. Bonaventure.8 In many ways, the Reformation brought an intensification and also a growing popular dissemination of spirituality. Martin Luther, for example, differentiated between an “external” and an “inner” man (or human being) and clearly associated spirit—chiefly the Holy Spirit—with human inwardness.9 At the same time, the Reformation released spirituality from its earlier clerical confinement (in accordance with the idea of the “priesthood of all believers”). Still more recently, partly as a result of Romanticism and pro...