![]()

PART ONE

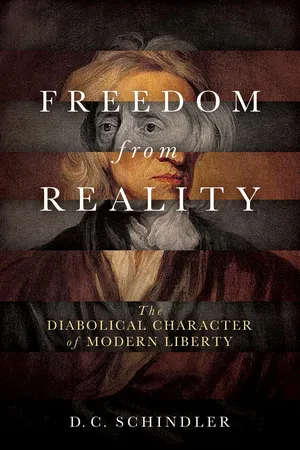

John Locke and

the Dialectic of Power

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Locke’s (Re-)Conception of Freedom

We enter into our reflection on the modern conception of freedom with a discussion of John Locke, not necessarily because he is the most influential or important of the early modern philosophers—though Lee Ward certainly has some justification for calling him “the canonical figure of Western liberalism”1—nor even because his interpretation of the nature of freedom is exceptionally clear. In fact, his writing on this topic is notoriously difficult to decipher, to such an extent that it has appeared to be not just confusing, but confused: as a contemporary critic observed regarding his attempt to explain the nature of freedom, “Here even Locke, that cautious philosopher, was lost.”2 The reason we choose Locke is because of the basic ambiguity in his thinking about freedom rather than in spite of it. The larger claim that we intend to make is that the modern conception of freedom has an inherent, indeed logical, tendency to subvert itself, and we aim to show in our first two chapters that this tendency comes to a certain perfection of expression in the thinking of Locke.

It is well known that conflicts in interpretation have attended the reception of Locke’s idea of freedom from the first moment of the publication of his Essay Concerning Human Understanding in 1690,3 and only intensified with his attempts to clarify his conception of freedom in the subsequent revised editions of the book.4 Indeed, it was precisely the chapter that dealt with the question of free will, namely, the twenty-first chapter of the second book, already one of the longest in the Essay, that was subject to the most revision.5 To put the controversy in modern terms: Is Locke a compatibilist, who believes (like Hobbes) that our actions are free but the volitions that produce those actions are not? Or is he a libertarian who thinks that, no matter how much one might be influenced by outside determinants, the will has the final say, so that we are justified in taking the will to be an absolute cause, and so to be accountable ultimately only to itself for its choices? Contemporary scholarship on Locke’s notion of freedom has continued to struggle with resolving the problem of determining where Locke stands on the question of the will’s freedom.

The difficulty can be set forth in a rather straightforward manner, though we will have to dwell on many of the details later in our discussion. In the initial edition of his Essay, Locke seems—though not without ambiguity even here, which is attested to by the immediate controversy—to incline toward a compatibilist perspective, that is, to hold that there is a freedom of action but a natural determinism of the will. This is something that concerned Locke when he finished, and, as he explains in a letter to William Molyneux—an admirer of Locke’s, with whom Locke began to take up correspondence after the publication of his Essay—it was a tendency that emerged in the writing, contrary to his intentions as he began.6 Locke says in the first edition that it is ultimately nonsensical to ask whether the will is free, since the category is intelligible only in relation to agency, and the will is not itself an agent but the faculty of an agent. The will is not self-determining, but it is determined in every situation by the greatest good that presents itself in that situation. “Upon a closer inspection into the working of men’s minds, and a stricter examination of those motives and views they are turned by” (“Epistle to the Reader,” 16), however, and prompted by questions friends and critics had raised, he felt a need to revisit the problem. In response to Locke’s request for a critique, Molyneux admitted that Locke seemed to espouse a kind of intellectualism that failed to give due weight to the self-determining power of the will and was thus unable to explain the will’s tendency to stray from reason—that is, the classic problem of akrasia (“incontinence” or “weakness of will”). In Molyneux’s words, Locke appeared “to make all Sins to proceed from our Understandings, or to be against Conscience; and not at all from the Depravity of our Wills.”7 Moreover, Molyneux sent to Locke notes an acquaintance of his, Bishop William King, had made, which articulated in strong words a complaint that Locke failed to grasp the will’s self-determining nature, rendering it a “passive power”: whereas Locke had said that one can ask for no more freedom than to be able to act in accordance with one’s will, King insisted this is true only if “that will not be crambed down his throat, but proceed meerly from the active power of the soul. [W]ithout any thing from without determining it to will or not to will.”8 In the second edition, Locke sought to mitigate the role of external determination by strengthening the agent’s power, in a manner we will explore in detail below.

What is curious is that, although Locke makes what appear to be decisively new qualifications in the second edition (and also in the fifth), which fundamentally modify one’s view of what freedom is, he added them to his original ideas as a supplement without in fact changing much of the substance of what he had previously written.9 It may be true that, in the second edition’s “Epistle to the Reader,” he admits to having changed his mind about the question, but he also suggests in the text (and explains in a letter to Molyneux) that the change amounts to little more than the substitution of “one indifferent word” for another, “actions” for the word “things,” which he had used in the first edition.10 The change of understanding he confesses would thus appear to be rather slight. And so there seem to be several interpretive options available here, which we can boil down to the three most evident. Either (1) Locke was originally a compatibilist, but as a result of his closer consult of evidence and experience, and discussion with others, he altered his position and became a libertarian. Or (2) he was always a compatibilist, even in the later editions of his work, and what seem to be changes are in fact better interpreted as clarifications of his prior position or qualifications of his original position that would allow him to accommodate apparently contravening evidence without abandoning that position. Or, finally, (3) he was always a libertarian, and the ideas he introduced in subsequent editions merely enabled him to bring out more clearly and forcefully what was essentially a part of his thinking from the beginning. Serious scholars can be found defending each of these three interpretations.11

What we wish to propose is that the reason a serious defense of each of these three opposed interpretations of Locke can be found is that they are all exactly correct. Locke’s view of freedom, in its final form, can be justifiably interpreted either as compatibilist or as libertarian, because the inherent logic points, as it were, in both directions at the same time. It is interesting in this context to note that, in the development of psychology in the centuries that followed, both the “associationists,” who tended to be determinists, and the “faculty psychologists,” who tended to be libertarians, pointed to Locke as the father of their school of thought.12 Locke himself was evidently committed to preserving a full sense of human freedom, while at the same time he was resolute in his desire to avoid any tendency toward blind, arbitrary spontaneity. Because it is the logic of his conception that bifurcates simultaneously in these two directions, it becomes relatively unimportant for the purposes of our investigation what he himself intended to achieve. In what follows, therefore, our interest lies above all in the philosophical implications of his core ideas, rather than his own comments on them, or how his ideas were received by his contemporaries. To show these implications requires a much more precise presentation of those ideas, and so it is to this task that we turn first.

ON POWER

Let us first recall the context of Locke’s presentation of his notion of freedom. The treatment comes in volume 2, chapter 21, of the Essay, which is entitled “Of Power.” The general argument of the Essay is to show that the human mind is essentially a “white sheet,” a blank piece of paper, which gets filled with content through the experience of the world: the Essay is thus a “natural history of the mind,” in the sense that he follows an empirical, historical method in his interpreting the activity of the mind.13 To make this argument, Locke attempts to show the genetic origin of our ideas in experience, first the simple ideas that we have, which cannot be reduced to anything more basic, and then the complex ideas, which are constructed upon those simple ideas and usually involve relations between several of them. The notion of power is a simple idea, according to Locke (2.7.8), which means that it is a univocal concept—“nothing but one uniform appearance, or conception in the mind,” which “is not distinguishable into different ideas” (2.2.1.145; all emphasis we have throughout the book for Locke is in the original unless otherwise noted)—and thus is derived in an immediate way from sensation and reflection.14 In the context of this first mention, he notes just that the simple idea of power arises from the experience of different forms of change (2.7.8.163). To say that it is a simple idea means that “power” cannot be defined, though it can be known only by acquaintance with the experience of change.

But Locke returns to elaborate the notion of power as a “simple mode” (as distinct from a “mixed mode”), which is a variation on a simple idea that does not involve the introduction of another idea. What Locke means by classifying power as a “simple mode” is apparently that it can be further differentiated within itself without the introduction of some other simple idea. The elaboration of the notion of power occurs in chapter 21, just before Locke turns to the “mixed modes,” that is, combinations of simple ideas, the first of which is the notion of substance.

Now, the reason Locke focuses this lengthy and complex chapter on power almost exclusively on the experience of the human will is that an exercise of the will, according to Locke, is the sole experience from which we are able to derive the notion of power. The reason that it is exclusively our own exercise of will that affords a notion of power is that, as Locke explains, it is only here that we see power in its most proper, active sense as the ability to bring about a change, as distinct from power in the passive sense as the ability to undergo a change. Clearly, the active sense is primary, insofar as the changes that one thing undergoes have to be produced actively by something else.15 Although it is true that we witness the effecting of change constantly in the world around us, it is nevertheless also true that every event can be causally traced to the precedent conditions, and so on: as Locke says regarding physical body in the natural world, “we observe it only to transfer, but not produce any motion” (2.21.4.312). The activity of the will presents a contrast to this: “The idea of the beginning of motion we have only from reflection on what passes in ourselves” (2.21.4.313).

The crucial question that arises here is whether the exercise of the will is in fact a beginning of motion—as we will see, it is just this question that Locke never definitively manages to answer. It is therefore no surprise that the question of freedom would continue to occupy Locke in later editions. We need to note the importance of this point. The notion of power is not just one of the various ideas that Locke reflects on in his account of the mind and its contents, but it represents, as Pierre Manent has suggested, the very center of the Essay, the reference point for all of the most significant notions he goes on to describe.16 Indeed, once we consider the pragmatic turn of Locke’s thought generally, we may say that the notion of power is the heart of his philosophy simply: it is the basis of his metaphysics, insofar as it presents the “principal ingredient” (2.21.3.311) of his notion of substance and of cause and effect; it is the basis of his epistemology, since all perceived qualities of the world are expressions of the power that things exert on the mind; it is the heart of his anthropology, since in rejecting all innate ideas he nevertheless founds his interpretation of human nature on the basis of innate powers;17 and, needless to say, Locke conceives the goal of political philosophy to be the proper distribution of power:

The Great Question which in all Ages has disturbed Mankind, and brought on the greatest part of those Mischiefs which have ruin’d Cities, depopulated Countries, and disordered the Peace of the World, has been, Not whether there be Power in the World, nor whence it came, but who should have it.18

If the notion of power, around which so much turns, can be derived from nowhere else but an insight into the will as a beginning of motion, then a proper interpretation of will is a matter of no small concern for the success of Locke’s philosophy. His revision in this respect is not a matter of satisfying his critics, but of satisfying the demands of his own thinking.

VOLITION AND FREEDOM

Having considered the context in which Locke’s discussion of human freedom occurs, and what is at stake for him in this discussion, let us now turn to the details of the discussion itself. Locke’s definition of freedom appears quite straightforward, but it turns out to be rather complex when he attempts to elaborate and justify the elements of that definition. In the tightest nutshell, to be free, for Locke, is “to have the power to do what [one] will.”19 Locke explains that the power to do a particular thing is free only if it includes also the power not to do it. This aspect, which is one of the things that distinguishes his view from that of Hobbes, is so much a part of the essential meaning of freedom in his understanding as to require explicit mention in the more precise elaboration of the definition, which he thus gives as “a power in any agent to do or forbear any particular action, according to the determination of the mind” (2.21.8.316).20 That this represents his definitive understanding of freedom, whatever qualifications he eventually adds, becomes evident when he refers to it again, towards the end of his life, as the settled definition. In letters to his Arminian friend Phillip van Limborch, in a debate they had concerning the indifference of the will, Locke affirms that freedom “consists solely in the power to act or not to act, consequent on, and according to, the determination of the will,”21 and “Liberty for me is the power of a man to act or not to act, according to his will: that is to say, if a man is able to do this if he wills to do it, and on the other hand to abstain from doing this when he wills to abstain from doing it: in that case a man is free.”22

As these formulations reveal, freedom for Locke concerns above all action. According to Locke, man has an active power to perform (or refrain from performing)—tha...